- India

- International

Explained: Why has China put Uighur Muslims in camps, and what happens inside?

Around a million Uighurs, Kazakhs and other Muslims have been bundled into ‘de-radicalisation camps’ in China. Those not detained are living under constant surveillance, involving facial recognition cameras and QR codes on homes.

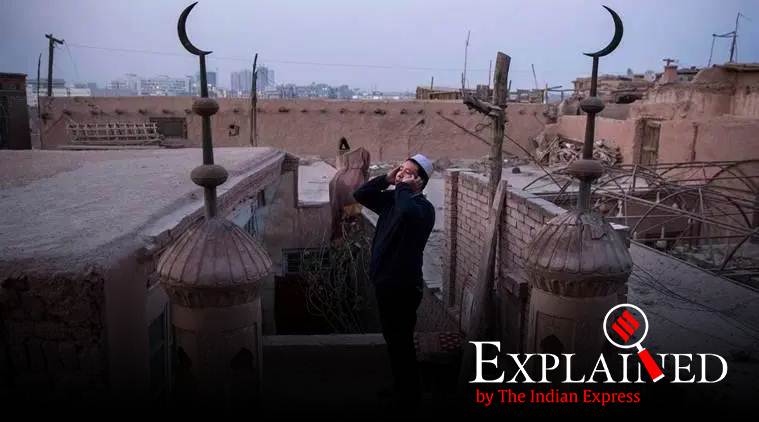

A muezzin sounds the call to prayer from the roof of a mosque in Kashgar, in China’s far western province of Xinjiang (The New York Times: Adam Dean)

A muezzin sounds the call to prayer from the roof of a mosque in Kashgar, in China’s far western province of Xinjiang (The New York Times: Adam Dean)

For some months now, international concern has been growing about what China is doing to its Uighur population, a Muslim minority community concentrated in the country’s northwestern Xinjiang province. Reports have emerged of China ‘homogenising’ the Uighurs, who claim closer ethnic ties to Turkey and other central Asian countries than to China, by brute — and brutal — force.

Around a million Uighurs, Kazakhs and other Muslims have been bundled into internment camps, where they are allegedly being schooled into giving up their identity, and assimilate better in the communist country dominated by the Han Chinese.

Children have been separated from their parents, families torn apart, an entire population kept under surveillance and cut off from the rest of the world. The few survivors who have managed to escape the country have been reported to speak of physical, mental and sexual torture at these camps.

China resolutely denies all such allegations, claiming the camps to be ‘educational centres’ where the Uighurs are being cured of “extremist thoughts” and radicalisation, and learning vocational skills.

Recently, however, a set of leaked government documents have reached The New York Times, giving a behind-the-scenes look into how and why the camps were set up, what is happening there, and what the government seeks to achieve from them.

What exactly are these documents?

According to The New York Times, “the papers were brought to light by a member of the Chinese political establishment who requested anonymity and expressed hope that their disclosure would prevent party leaders, including [President] Xi [Jinping], from escaping culpability for the mass detentions.”

The newspaper says the leaked papers consist of 24 documents, which “include nearly 200 pages of internal speeches by Xi and other leaders and more than 150 pages of directives and reports on the surveillance and control of the Uighur population in Xinjiang.

There are also references to plans to extend restrictions on Islam to other parts of China.”

A reeducation camp for ethnic Uighur in Hotan, in China’s Xinjiang province. (The New York Times: Gilles Sabrié)

A reeducation camp for ethnic Uighur in Hotan, in China’s Xinjiang province. (The New York Times: Gilles Sabrié)

Why is China targeting the Uighurs?

Xinjiang is technically an autonomous region within China — its largest region, rich in minerals, and sharing borders with eight countries, including India, Pakistan, Russia and Afghanistan.

The Uighurs are Muslim, they don’t speak Mandarin as their native language, and have ethnicity and culture that is different from that of mainland China.

Over the past few decades, as economic prosperity has come to Xinjiang, it has brought with it in large numbers the majority Han Chinese, who have cornered the better jobs, and left the Uighurs feeling their livelihoods and identity were under threat.

This led to sporadic violence, in 2009 culminating in a riot that killed 200 people, mostly Han Chinese, in the region’s capital Urumqi.

In 2014, President Xi visited Xinjiang. On the last day of his trip, a suicide bombing at a railway station in Urumqi killed one person and injured nearly 80.

Weeks previously, Uighur militants had gone on a stabbing spree at a railway station, killing 31. The following month, in May, 39 people were killed in a blast in a vegetable market in the region.

The government had anyway been cracking down on the Uighurs. After this spell of violence, retaliation hardened.

With terror attacks in other parts of the world and the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, a local militancy was viewed as something that could grow into a terrorist-secessionist force, determined to break away from China to form an independent “East Turkestan”.

The Chinese policy from hereon seems to have been one of treating the entire community as suspect, and launching a systematic project to chip away at every marker of a distinct Uighur identity.

Patrons dine under posters quoting Xi Jinping, reading “every ethnic group must tightly bind together like the seeds of a pomegranate,” at a restaurant in Yarkand, in China’s Xinjiang province (The New York Times: Gilles Sabrié)

Patrons dine under posters quoting Xi Jinping, reading “every ethnic group must tightly bind together like the seeds of a pomegranate,” at a restaurant in Yarkand, in China’s Xinjiang province (The New York Times: Gilles Sabrié)

What is happening in these camps?

People could be sent to the government’s “deradicalisation camps” for showing any signs of extremism, with the government deciding what was “extremism” — sporting beards, fasting during Ramzan, dressing differently from the majority, sending Eid greetings, praying “too often”, giving up smoking and drinking, or not knowing Mandarin.

The brighter of the Uighur children were sent to boarding schools and colleges so they could be honed into civil servants loyal to China.

In three years, the government is estimated to have put one million people in the “re-education” camps, making them leave behind their jobs, property — and their children.

The building of the internment camps has been accompanied by a hectic building of boarding schools and kindergartens. Children whose guardians have been taken away are being put in these facilities, where one of the things they will be taught is loyalty to China.

From inside the internment camps have come reports of torture.

A former inmate told the BBC: “They wouldn’t let me sleep, they would hang me up for hours, and they would beat me. They had thick wooden and rubber batons, whips made from twisted wire, needles to pierce the skin, pliers for pulling out the nails. All these tools were displayed on the table in front of me, ready to use at any time. And I could hear other people screaming as well.”

A woman has spoken of how she saw a fellow inmate die for want of medical attention to menstrual bleeding, and how the camps were so crowded they had to stand and sleep in shifts.

The documents leaked to The NYT speak of the official line prepared for the children of inmates who have returned from colleges — “elite” children with connections to social media and other parts of China.

They are told they should be grateful the government is taking pains to reform their relatives “infected by the virus” of radicalism. Those who still persist with questions are told there is a credit system in place to decide when the inmates can leave the camps, and their behaviour will impact their relatives’ credit.

Because the inmates have not been charged for any crime, there is no question of a legal fight against their detention.

But even those who are not in the camps are not quite free. The government has put in place a surveillance system that includes face recognition cameras, software to monitor Uighurs’ phone activities, QR codes on homes that tell authorities how many members are inside the house, QR codes on any domestic tool that can be used as a weapon, such as a knife.

Contacting people outside China is one of the surest ways to be sent to a camp.

The government claims it is providing the inmates vocational skills, but many of those detained are professors, doctors, skilled professionals, so it is not clear what are these “skills” are supposed to achieve.

What is the role played by the Chinese leadership?

The NYT leaked documents claim there is a large personal footprint of President Xi in his country’s Uighur policy.

The NYT report says: “President Xi Jinping, the party chief, laid the groundwork for the crackdown in a series of speeches delivered in private to officials during and after a visit to Xinjiang in April 2014… Setting aside diplomatic niceties, he traced the origins of Islamic extremism in Xinjiang to the Middle East and warned that turmoil in Syria and Afghanistan would magnify the risks for China. Uighurs had traveled to both countries, he said, and could return to China as seasoned fighters seeking an independent homeland, which they called East Turkestan.”

Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, who was general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party from 2002-12 and President of the People’s Republic from 2003-13, believed in economic development alongside a state crackdown to wean people off violence, and to integrate them better with China.

According to The NYT report, the state took a dim view of allowing people too many human rights.

“…A 10-page directive in June 2017 signed by Zhu Hailun, then Xinjiang’s top security official, called recent terrorist attacks in Britain “a warning and a lesson for us”. It blamed the British government’s “excessive emphasis on ‘human rights above security’ and inadequate controls on the propagation of extremism on the internet and in society,” The NYT report says.

Local officials had had misgivings about the government’s tough policy, fearing it would exacerbate the ethnic divides in the region. But officials perceived as too kind to Uighurs were punished, swiftly and publicly.

What has been China’s stand officially?

Over the past year, Turkey has spoken up for the Uighurs, and the United Nations and the United States have made some noise. China has maintained it is only de-radicalising some of its errant citizenry, and has asked the world to “respect its sovereignty” in dealing with its internal matters.

However, in January this year, after reports of torture and abuse by some human rights organisations and media houses, the Chinese government invited a few journalists and diplomats to visit the camps.

The inmates told the journalists they had seen the error of their ways, were glad the government was reforming them, and also danced to “If You Are Happy And You Know It Clap Your Hands.”

After The NYT documents were made public, Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of China’s Global Times, tweeted: “ I don’t know if the documents NYT reported is true or false. But I am certain Xinjiang has seen dramatic changes: Peace, prosperity and tourism are back. Xinjiang borders Pakistan and Afghanistan, China’s de-radicalization efforts have made Xinjiang different from them.”

A day later, China’s foreign ministry accused the NYT of ignoring the reasons the camps were built. Spokesman Geng Shuang said: “It [NYT] is hyping up these so-called internal documents to smear China’s efforts in Xinjiang. What is the agenda? Xinjiang’s continuing prosperity, stability, ethnic unity and social harmony are the strongest refutation to the allegations by certain media and individuals.”

Also read | Explained: Why are Iranians protesting on the streets?

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05