- India

- International

My parents bequeathed to me a lived liberalism. From Dec 6, 1992, that virtue, that country, is besieged

The dream had communicated a message: That if young men armed with just axes, hammers and uncontrollable rage could reduce a 16th-century mosque to rubble as they had done that day, the bare bones of the virtues required to challenge them might lie beyond the boundary of time.

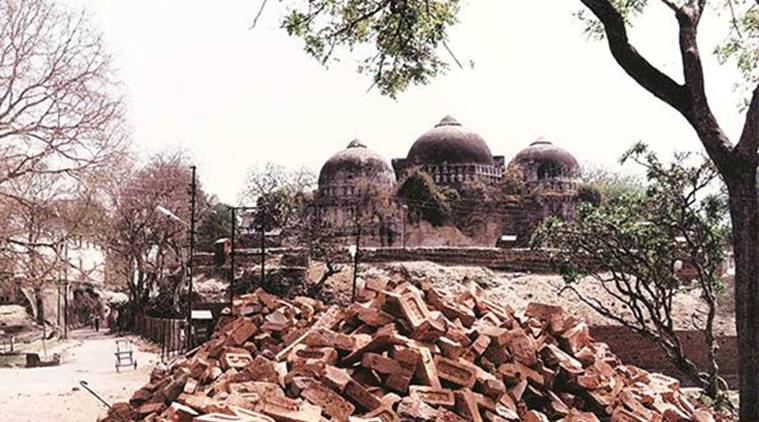

Babri Masjid in the background.

Babri Masjid in the background.

I had a dream on the night of December 6, 1992, the day the Babri Masjid was destroyed.

It went like this:

My parents and I are travelling in an open top safari-style jeep. We are looking over the sides, scanning the trees on either side of the rough road, searching for something. And then one of us shouts to indicate they had spotted something and we come to a halt and scramble out. Pulling the thick undergrowth aside, we find what we are looking for — large white human bones, that resemble the rounded form of Henry Moore’s sculptures. My father says, “there he is, there is Gandhi. We can take him back with us now”. As we lift the pieces carefully, we realise that in our frantic search we had unknowingly crossed a line, a border of some sorts, across which “Gandhi” lay. Realising we would not be allowed to bring him back from across the border, we lower the pieces we had so eagerly picked up and drive back the way we came, looking over our shoulders and thinking how close we had come to the treasure we could not claim.

I have only once in my life had a dream like this, but it has stayed with me forever. I remember narrating it to my doctoral supervisor in his Oxford office. Even though its vividness felt real, it had come across as embarrassingly heavy with meaning and symbolism in the telling and so I rarely spoke of it again.

But the dream has never gone away and this year especially, it gives expression to inchoate emotions that have dominated the last few months. This will be the first December of my life without my parents. My mother died exactly two years ago, on my parents’ 56th wedding anniversary and my father at the end of May this year, a week after the new Indian government took office. With them, they also seemed to have taken an India that they had given my generation and me. An India that had a sense of common purpose even if labelled “under-developed”, confident if poor, an India that treasured the memories of hard-won independence and the thrill of the Indian flag hoisted on flagpoles for the first time, an India that stood tall but did not look down on others. My parents were the sort of Indians that made India a knowledgeable, modest, hard-working, understated, respected and likeable country. That India has now been replaced by a “new India”, we are told.

We were an ordinary professional family with few luxuries as the bulk of the household budget was spent on school fees and hosting relatives, for whom our government bungalow near New Delhi railway station was a god-sent waiting room as they “broke” long train journeys, went to job interviews or waited to rent their own homes. Our paternal grandmother was a more permanent (and more welcome) member of the household, who gently carried on her iron Brahmanical discipline of early morning baths, fasting and puja, regulating her life by the five azaans from the mosque behind our house.

Eid was a time of feasting as grateful patients of my father’s, drawn from the ragged underclass of mechanics and tailors of old Delhi, arrived at our home with delectable offerings of meat and biryani. My strictly vegetarian grandmother did not taste these of course but she delighted with us in the sudden luxury and happily tasted the sevai from the kitchen of Dr Ahmed, the principal of Zakir Hussain College who lived next door. Christmas was always spent with Stella Aunty, my mother’s best friend and colleague from the elite school where my mother taught physics.

My parents were not, however, members of the elite of Lutyens Delhi. They had never travelled abroad, they spoke English only when they had to, and always felt slightly out of place in snobbish Delhi where your address, accent and precise provenance of the handloom you were draped in were critical markers of social distinction. They lived there because that is where they had found work, because they were devotees of Delhi’s wonderful classical music concerts and most of all because they knew the city offered untold treasures for their daughters’ growing interests in everything from fantastic universities, world cinema festivals and ballet lessons. They delighted in our rapidly growing horizons, fluency in English and our social ease in the big city for they knew that it would open doors of opportunity and do justice to the unconventional upbringing they had given us.

Dinner time was marked by each of us sharing stories from our day, of people, food, places and ideas we had encountered and we learnt of their lives in the small towns they had grown up in, how they had to learn to adjust to other kinds of Indians when they had started their working lives and during my father’s years in the Army, and how much richer life had got the more they embraced new influences. Their commentary on the anecdotes also showed that not everything in our country was good and that it was important to stand up to patriarchy, religious dogma and the inhumanity of caste, for each of which they had zero tolerance.

These were never presented as ideological statements, although my mother occasionally cited characters and writings from Bengali literature to illustrate her thoughts, we learnt mostly from what they did and how they led their lives. For instance, we noticed that my mother patronised an old woman vendor even though her vegetables looked sad, we heard that my father had thought nothing of first cleaning the filthy foot of a fishmonger, when during a shopping trip “Doctor saab” was requested to examine a wound, and we saw how the domestic staff they employed over the years left better educated and more confident than when they arrived. What my parents imparted to us, in imperceptible ways, were some basic virtues of civility and warmth, to be fearless in acting against injustice wherever one encountered it, to shun bigotry and to be quiet in pride.

It was perhaps those virtues that I had gone in search of in the dream. My imagination had given them the physical form of Henry Moore limbs and the name “Gandhi”. But in essence, I realise now, the dream had communicated a message: That if young men armed with just axes, hammers and uncontrollable rage could reduce a 16th-century mosque to rubble as they had done that day, the bare bones of the virtues required to challenge them might lie beyond the boundary of time.

In my dream, my parents had been with me, but now their legacy of a liberalism of practice is my only companion as I seek to reclaim those virtues.

This article first appeared in the print edition on December 6, 2019 under the title “A vision in a dream, a fragment”. Banerjee is director, LSE South Asia Centre and author of Why India Votes?

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05