- India

- International

December 16: For rape survivors, the nightmare rarely ends

Rarely understood is the story of what happens after the rape. To investigate that, The Indian Express travels to a counselling centre in Dewas, speaks to rape victims, doctors and police to find that for the survivors of rape, the nightmare rarely ends

The spot where the Unnao rape victim was set on fire

The spot where the Unnao rape victim was set on fire

Tomorrow marks the seventh anniversary of the rape in Delhi that convulsed the nation — the tremors of which are felt to this day. So when police kill four suspects of a rape in Hyderabad last week, there is a disquieting applause. Rarely understood is the story of what happens after the rape. To investigate that, The Indian Express travels to a counselling centre in Dewas, speaks to rape victims, doctors and police to find that for the survivors of rape, the nightmare rarely ends

Her tear-stained face is covered in tiny, red eruptions. It’s not chicken pox or teenage acne, she confirms. A few wounds on her neck — throbbing blotches of purple — are yet to heal. And when she walks, she switches between a hobble and a heavy limp. “I wasn’t this way two months ago,” she says impassively.

Two months ago, the 17-year-old was gang-raped by three men — a 17- and an 18-year-old from her village in west-central Madhya Pradesh, and a 45-year-old from a neighbouring village. She was on her way to visit a tailor, when the men abducted her, held her hostage for one month and five days — “I kept count,” she says — and repeatedly raped her. “They didn’t give me any food, and beat me up,” she says, dressed in a kurta, which hangs loosely over her skeletal frame.

Only a few moments ago, she had recounted the horrors of those days to a counsellor of Jan Sahas, an NGO that works with rape victims and other underprivileged women, in Dewas in Madhya Pradesh. This is her first counselling session since the rape and she puts her head down and repeats a story she has told several times before, to her family, police, in court.

As another anniversary approaches of the 2012 Delhi gang rape case that had jolted the country and resulted in a series of policy reforms, including the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 that broadened the definition of rape, two recent incidents — the Hyderabad case where the rape accused were killed in an ‘encounter’, and the recent Unnao case in which the victim was burnt to death by her alleged assaulters — have again made rape and meaning of justice national conversation.

But, as the Parliament session ending on an unceremonious note on December 13, also over rape, showed, mostly, that conversation is little more than noise.

Tough law, poor execution

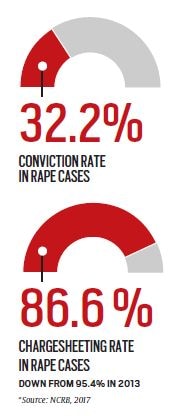

Following the December 2012 gang rape, the Parliament passed the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013, which expanded the definition of rape and increased sentence for accused. The following year, the Health Ministry too issued guidelines for medico-legal care of survivors. However, with health being a state subject, not all states have adopted the guidelines, and implementation on the ground has been found wanting. Experts believe that the low conviction rate in cases of rape — 32.2% at the national level — is also a reflection of this indifference, which results in shoddy investigation and collection of evidence, poor medical care, and lack of emotional support systems for survivors.

According to the latest National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report, in 2017, 33,885 women were raped in India, of whom 227 were murdered. A total of 28,152 children were raped and, of them, 151 were killed after the incident. Uttar Pradesh recorded the maximum number of crimes against women (56,011), and Madhya Pradesh, with 5,562 cases, recorded the highest number of rapes.

The 17-year-old’s bruised exterior does not fully reveal the extent of trauma that the survivor and her family have been going through since she was assaulted. More often than not, victims seeking help in the immediate aftermath of a rape encounter a creaking, hostile system — slapdash investigation, negligent medical care, absence of emotional support, a legal battle that threatens to go on for too long, and social ostracisation.

Read | In village of Unnao rape victim, girls ‘waiting to get out’

First hurdle: Filing complaint

The 17-year-old’s father, a Dalit daily wager, says he has been staying up nights wondering if his daughter could have been saved if police had registered his complaint on time. “They first told me bhaag gayi hogi (Your daughter would have run away). When I persisted, they threatened me. Even after my daughter was rescued, only two of the accused, both tribals, were arrested. The man from the neighbouring village, an upper caste Patidar, was let off… I suspect he bribed the policemen,” he says.

“The room they kept me in was his. The entire thing was his idea,” says the 17-year-old of the man who was let off on bail.

D Roopa Moudgil, IGP, Railways, and former DIG, Prisons, Karnataka, admits that in many cases, even getting a rape case filed, especially in rural parts, is a challenge. “There are instances of victims being driven away. Policemen make allegations against the complainant… The manuals and guidelines are all in place. There are programmes held for sensitisation of police officers as well… In many cases, despite rules, a woman officer is not present while the survivor’s statement is recorded,” she says.

Back in 2006, the NCRB estimated that about 71 per cent of rape crimes go unreported in the country.

Vijayanta Arya, DCP, North-West Delhi, who has handled several rape cases in the Capital — which, according to Delhi Police statistics, recorded a daily average of five or more rapes in 2018 — says the reporting and investigation gets tougher when the rape has happened long ago. “It is difficult to corroborate the event, important biological evidence is lost, CCTV and CDR (call detail record) analysis is difficult or not possible, and if the crime has occurred in a hotel etc, the visitor logs may have been misplaced,” she says, adding that in such situations, not just the police, the entire ecosystem of family, doctors and counsellors, have to be in sync to build a robust case.

IGP Moudgil also emphasises the role of the supervisory officer (an IPS officer) in seeing a case through. “Many instances of laxity do not come to light because the supervisory officer doesn’t pay heed. But that’s also because they too are burdened with bandobast, VIP duty… What we need is dedicated staff.”

Jayashree Velankar, Director, Jagori, a women’s rights group that has been working with victims for many years, says police also need to change the way they perceive rape cases. “In many police stations, there are blackboards with lists of cases solved. Never have I seen a rape case on that list. That’s because while an officer is promoted for cracking a murder case, there is no such incentive for solving a rape case. They look at it as an additional burden,” she says.

The other aspect that weighs heavily on investigators is public anguish, like in the Hyderabad case. “There are people baying for the blood of the accused. How does one assuage and control that? It’s a huge challenge,” says retired IPS officer and now Lieutenant Governor of Puducherry Kiran Bedi.

She says that while investigation “has improved to an extent, there is still not much police mobility and presence on the ground”. “Even grassroots and community policing to ensure prevention of crimes is nil. (And, since the Delhi gang rape) while we have extremely tough laws, we have also not come very far in terms of fast trials,” she says.

In light of the Unnao case this year, Bedi also puts the onus on the judiciary “to ensure stiff bail conditions for the accused”. Two of the men who set the Unnao victim on fire are her alleged rapists, who were out on bail.

Read | In district of Dec 16 gangrape, dip in crimes against women, convictions dismally low

Citing “police apathy” in the other Unnao case — the 2017 kidnapping and rape of a woman, allegedly by expelled BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar — Jyotika Kalra, a member of the National Human Rights Commission and a former Supreme Court lawyer, says investigators usually let the victim down in most cases. “When the Unnao victim went to the police to file a complaint, they did not do it. She had to go to court for it. This happened when the case was playing out in public….” she says.

IGP Moudgil says police have to ensure that the bail conditions laid out by courts are monitored. “The rules mandate it, but again, on the ground, that may not be the case.”

Medical exam, forensics

The 17-year-old’s medical examination did not take very long. “Five to ten minutes,” she recalls. “My body was full of bruises… I was asked to remove my clothes… Bohot dar lag raha tha (I was very scared). Bas slide test kiya (Only a vaginal swab was taken). Nothing else,” she says. She was also subjected to the controversial two-finger test.

Medical examination, says Jagori’s Velankar, is most crucial to prove the crime in court. “Apart from the vaginal swab, samples from nails, all oral cavities, including ears, are a must. However, a large number of hospitals, especially those in rural India, do not have the requisite kits to conduct these tests,” she says, adding that while the two-finger test may not be prevalent in cities, it’s common in smaller towns.

Even after the evidence is collected, its preservation has often been found wanting. “It is not just about putting things in a packet. Many a time, the forensics are not correct because the preservation has not been done according to the guidelines,” says Moudgil.

Kalra points to the degradable nature of medical samples that need more care than other evidence. “At this stage, you need trained doctors, and the overburdened staff at government hospitals may not be adequately equipped for it,” she says.

These samples, however well preserved, then enter the choked system of forensic labs — there are seven such laboratories in the country to which go all cases that need forensic analysis, including rape.

According to Gordon Thomas Honeywell- Governmental Affairs, an international public affairs firm that focuses on forensic DNA policy, “DNA testing is done only in 7,500 cases in India annually” — a poor number when compared to countries such as the United Kingdom, which have a much smaller population, and where “over 60,000 such tests are conducted annually”.

Also, like in the case of the 17-year-old, the treatment for victims often falls short. “I could not tell the doctors about my pains. Apart from the boils on my face, it also hurts when I relieve myself… There is a discharge at times too,” she says. Her father pitches in, “She has not been eating since she was rescued by the police.” “I feel repulsed by food,” she says.

In 2014, the Health Ministry issued guidelines for the medico-legal care for survivors which states that “sexual assault victims cannot be denied treatment… Denial has…been made a…criminal offence punishable with… jail terms or fines or both”. However, says Manju of Jan Sahas, most survivors who come to them, such as the 17-year-old victim, struggle to get access to medical care.

“In rural parts, the medical staff is mostly concerned with examination. They just want to finish the job. However, many victims come with severe injuries which need medical attention. Also, the treatment may take many days and should be monitored. That awareness isn’t there,” says Velankar.

With health being a state subject, a 2017 study by Human Rights Watch, ‘Barriers to Justice and Support Services for Sexual Assault Survivors in India’, found that medical professionals, even in states that have adopted the 2014 guidelines, often do not follow them.

Read | As 2012 Delhi gangrape case moves towards closure, some questions on death penalty answered

Lack of emotional support

Earlier this year, the Women and Child Development Ministry said 462 One-Stop Centres (OSC), which would provide medical, legal, psychological and counselling support to victims of gender violence, have been set up across the country. Its costs are covered under the Nirbhaya Fund, a corpus fund established by the Centre security of women.

At one such OSC in Dewas, attached to the town’s Mahatma Gandhi Government Hospital, a case worker, a counsellor, a policewoman, and a representative from an NGO are working on the case file of a woman who has come with a domestic violence complaint. Since it was established in 2017, the centre has dealt with 436 cases, half of them of rape. There are five beds for victims to stay for five-seven days, two toilets and a bathing area. When a victim arrives, she is given a kit with clothes, oil, cream and comb. Doctors and lawyers are available on call.

The staff admits that the biggest challenge so far has been handling the emotional trauma of victims. “Some cry uncontrollably, some try to flee, bang on gates, they want to end their life… It’s a lot to deal with. We have now asked for a guard at night as well,” says head constable Savitri Devi, who, along with a case worker, stays the night at the centre.

Since the incident, the 17-year-old survivor has been finding it hard to sleep. “Bure sapne aate hain, jo mera saath ganda kaam kiya, uske (I get nightmares of the rape and torture),” she says. She hasn’t received any counselling from the government hospital and says she wasn’t aware of the OSC till she came in touch the NGO, that has been offering help through its counsellors.

Dr Nimesh Desai, director of the Institute of Human Behaviour and Allied Sciences in Delhi, where the Capital’s first full-fledged OSC started last month, believes counselling for victims of sexual assaults needs standardisation. “There is a need for a complete psycho-social support. Today, world over, there has been a major shift in mental healthcare, and we need more non-medical support. Unfortunately, we are still stuck with the old models that rely on medicines,” he says.

Apart from police sensitisation, Jagori’s Velankar also lays stress on training counsellors, who, she says, come with their own set of social prejudices. “What cannot be denied is that most of the staff at government hospitals look at these victims as an added burden. There is little empathy, and most things go against the girl. Even functioning of an OSC is a complex issue, and needs a lot of co-ordination,” she says, agreeing with IBHAS’s Desai on standard protocols for counsellors.

The fight in court

Since the incident, says the 17-year-old’s father, he and his daughter have made three trips to Dewas, where the case is being heard, traveling 200 km from their village. The visits are hectic, and they combine it with counselling and meeting with lawyers, to save costs.

“Every trip costs me Rs 500. I can’t afford it. She is also not keeping well, gets frequent fevers,” he says.

While still dealing with the system’s medico-legal maze, the family has also been facing ridicule in their village. “People tell me iski bacchi gayi (His daughter has been raped). The family of the accused say they will get me booked in a rape case too,” says the father of six. The 17-year-old is his youngest child and has studied till Class 8.

The NCRB data for 2017 pegs the conviction rate in rape cases at a poor 32.2 per cent at the national level, and lower, at 27.2 per cent, in metropolitan cities.

Vikas Suryavanshi, a lawyer at the Indore High Court who has represented several rape survivors, blames shoddy investigation for cases falling apart in courts. “Many a time, instead of filing a rape case under Section 375, police book the accused under milder sections, such as the one for a break-in. We have come across cases where the family of the accused bribes the police, who then put pressure on the victim to withdraw her complaint,” he says. “Also, police do not file chargesheet on time, within the stipulated 60 days, which results in bail for the accused.”

The NCRB data confirms this — the rate of filing chargesheets in rape cases has come down to 86.6 per cent in 2017 from 95.4 per cent in 2013.

After the Delhi gang rape case, state governments were also directed to fast-track cases of sexual crimes, and ensure that the trial is completed within 60 days. Legal experts, however, say that’s an ambitious target. “When we say fast-track, it’s not like a separate court has been built for it. It’s an added burden on the existing structures. Even the first judgment in the Delhi gang rape case took over a year, despite all the media attention,” says Velankar.

Recently, Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad said there are 704 fast-track courts for heinous offences and other crimes, and that the government will be setting up 1,123 dedicated fast-track courts for rape cases and for those under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO, 2012) Act.

Says an Additional Sessions Court judge in Madhya Pradesh who did not wish to be identified, “We have one of the toughest rape laws in the world. The courts too are trying very hard to fast-track all cases. In Madhya Pradesh, every district has a POCSO court. But, in my experience, 80 per cent of the times there is no conviction, and that is mostly because the victim turns hostile. Now, there may be many reasons for that, but as judges, we go by the victim’s statement. There is also the issue of witnesses turning hostile.”

IGP Moudgil says the laxity is often at the trial stage. “Since the cases run for so long, a witness tends to forget the statement they made earlier. It is the Investigating Officer’s job to brief him again. Then there are times when witnesses don’t appear in court, and that delays the case further. Also, our witness protection system isn’t very robust,” she says.

Read | Poor air and water, life getting short, why give death penalty: Dec 16 rape convict in SC

The road ahead

World over, the battle with rape has been a tough one. According to World Population Review, an independent United States-based firm that examines demographic data, South Africa, with 132.4 incidents of rape per 100,000 people, tops the list of countries with the highest rate of rapes. Even countries such as Sweden, which are hailed for their progressive gender laws, stands on the sixth spot with 63.5 incidents per 100,000 people. Developed nations such as the US, New Zealand, Australia, the Netherlands, all have poorer records than India.

Experts, however, say the focus should not be on safety rankings but on developing both preventive and post-crime interventions.

NHRC’s Kalra suggests the appointment of a point person, whom the rape victim can trust, to monitor all stages of the case. “Since the victim often has very little faith in the investigating officer, such a point person can serve as a protection officer,” she says.

Dr. Anjaiah Pandiri, executive director of Childline India Foundation, stresses on the need for follow-ups, especially in case of minor victims. “To ensure conviction, follow-ups by the all stakeholders is important through the course of the trial. It is important to ensure the child’s mental and physical well-being. The laws are in place, but its implementation and response of the police needs to be faster,” he says.

A police station in Tonk Khurd village, Madhya Pradesh, also offers some cues. “There are a few colleges around here, and girls were allegedly harassed while going to study. We were told that they felt scared to complain to the police. We had a spare building in the compound, and we have opened it up for the children and girls to come and study, play etc. So in the future, if any of them have a complaint, they can come to the station without fear,” says constable Shanu Sahi.

In the same village, NGO Jan Sahas has also set up a ‘Dignity Centre’, where girls come after school to learn, among other things, “good touch, bad touch”. Amu Vinzuda of Jan Sahas believes such efforts go a long way in changing mindsets inside homes.

Back in Dewas, as the 17-year-old prepares to take the 200-km journey back to her village after counselling, her father hopes she “eats something today”. He also has another concern, “I have been looking for a groom for her. Only then will this issue end for me.”

The 17-year-old withdraws her face into her dupatta, and walks behind her father.

Rape Statistics

33,885: Rapes in 2017

227: Murdered after rape

28,152: Children raped

151: Children killed after rape

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05