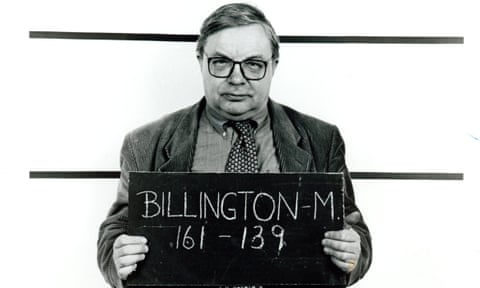

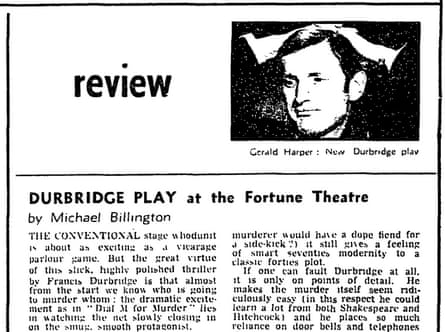

Durbridge Play

Fortune theatre, London, 2 October 1971

The conventional stage whodunit is about as exciting as a vicarage parlour game. But the great virtue of this slick, highly polished thriller by Francis Durbridge is that almost from the start we know who is going to murder whom: the dramatic excitement, as in Dial M for Murder, lies in watching the net slowly close in on the smug, smooth protagonist.

Company

Her Majesty’s theatre, London, 19 January 1972

How good is Company? When I saw Stephen Sondheim’s musical 18 months ago in New York, I thought it a marvellously tart, wry, original show that got away from all the lumbering cliches of the formula-bound Broadway musical. Second time round I admire it even more; partly because its surface exuberance seems to conceal a great sadness, partly because it has the whiplash precision of the best Broadway shows plus a good deal of intellectual resonance.

Not I

Royal Court, London, 17 January 1973

If Beckett has a painter’s eye, he also has a poet’s ear. The mouth belongs to a 70-year-old woman whose past life flashes before her, like that of someone drowning, but who transfers her experiences to someone else: the impression is of a buzzing skull, a mouth on fire helplessly attached to a body incapable of feeling. If I had to sum up the play’s theme in a phrase, it would be the anguish of memory at a time when all physical sentience had departed. Billie Whitelaw’s performance is an astonishing tour de force combining frenetic verbal speed with total sensitivity to the musical rhythm of the piece.

Ken Dodd

Liverpool Playhouse, 17 April 1973

Ostensibly, the intention is to explore the nature of laughter: in reality what we get is a king-sized Dodd-fest. It begins with those wayward teeth spotlit in what looks like a conscious parody of Billie Whitelaw in Beckett; and it goes on to run the gamut of Doddy jokes. Wisely, perhaps, Dodd avoids too much theorising. He quotes Freud’s opinions that a laugh is a conservation of psychic energy; but, as he says, the trouble with Freud is that he never played Glasgow second house on a Friday night.

Brassneck

Nottingham Playhouse, 21 September 1973

Brassneck by Howard Brenton and David Hare is an important play. Not since John Arden’s The Workhouse Donkey 10 years ago have I seen any work that attempts to put a whole regional community on stage and show in detail how the provincial power nexus works. Judging by the outraged huffing and puffing near me, it was courageous of Nottingham Playhouse to stage it.

Words of Advice

Greenwich theatre, London, 5 March 1974

Fay Weldon’s play is tight, tart and alert. In the centre of the ring are Tammy and Julia, a primary schoolteacher and his suffocating wife, who use each other like punchbags. Encircling them are their parents and in-laws who prefer contradictory, self-interesting advice. My gripe about the play is that its horizons are inevitably limited. It scarcely touches on the high cost of loving, on the way social inequity affects private relationships and on the crucial fact that even our emotional crises are carried on against the background of changing public events: only in plays do people have time to suffer in a vacuum. But Miss Weldon can certainly write.

The Tempest

Old Vic, London, 7 March 1974

Fourteen years ago precisely, Peter Hall began his brilliant Stratford reign with an over-decorated, eccentrically cast production of Two Gentlemen of Verona. We should not, therefore, despair if he has begun his National Theatre career with a lethargic, vulgarly spectacular, masque-like production of The Tempest that almost manages to submerge the presence of the greatest living Shakespearean actor, Sir John Gielgud, in opulent excess.

Bordello

Queen’s theatre, London, 19 April 1974

I have, I suppose, seen worse musicals than Bordello. Indeed I can wincingly remember one about refrigerated corpses and another about premature ejaculation at a certain north London engine shed. But it’s a long time since I’ve seen a show of such extravagant pointlessness or one that deployed such elaborate resources to convey a message that could be comfortably inscribed on the back of a 3½d stamp.

Travesties

Aldwych, London, 11 June 1974

I find it difficult to write in calm, measured tones about Tom Stoppard’s Travesties: a dazzling pyrotechnical feat that combines Wildean pastiche, political history, artistic debate, spoof-reminiscence and song-and-dance in marvellously judicious proportions. The text itself is a dense Joycean web of literary allusions; yet it also radiates sheer intellectual joie de vivre, as if Stoppard were delightedly communicating the fruits of his own researches.

Play Mas

Royal Court, London, 17 July 1974

Mustapha Matura’s Play Mas is an endearing, intelligent comedy. I only hope the work, playing at heavily reduced prices, gets through to the popular audience it deserves. Not that the play is by any means a mere colourful folksy romp. Even if everything in Trinidad stops for the annual gaudy Dionysiac rite, Matura shows that this cannot conceal either the social and political tensions or the interracial bitterness.

Autosacramentales

Roundhouse, London, 27 December 1974

I must be honest: I found Autosacramentales, an hour-long Victor Garcia production of a Calderon religious drama, almost totally inaccessible. Even with the help of programme notes and a pocket torch, I could not sort out Sin from Death, the Soul from the Body, or Cain from Abel.

No Man’s Land

Old Vic, London, 24 April 1975

Harold Pinter’s new play is about precisely what its title suggests: the sense of being caught in some mysterious limbo between life and death, between a world of brute reality and one of fluid uncertainty. But although plenty of plays, from Sweeney Agonistes to Outward Bound, have tried to pin down that strange sense of reaching into a void, I can think of few that have done so as concretely, funnily and concisely as Pinter’s.

The Big Red Ladder Show

Camden Town Hall, London, 6 December 1975

There was a cup final atmosphere last night at Camden Town Hall as a packed, exultant house roared its approval of the Red Ladder company’s new show, It Makes Yer Sick. The occasion was a benefit night for this spring-heeled leftwing troupe, who next month move to Yorkshire to set up a permanent base. I can only say that the north should count itself lucky, for this show is a model of what popular political theatre ought to be: festive, exuberant and theatrically pungent.

Macbeth

The Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, 10 September 1976

The simpler, the better; that is my feeling about Trevor Nunn’s ceaseless quest for the ideal Macbeth. Two years ago he staged the play in Stratford’s main house as an over elaborate religious spectacle. He then stripped away the ritual for an Aldwych version spoiled by gabbled speaking. And now, at Stratford’s Other Place in a production played without an interval, he has hit the right balance between verbal clarity and depraved religiosity; I have never seen the play come across with such throat-grabbing power.

Dusa, Fish, Stas and Vi

Mayfair theatre, London, 11 February 1977

Pam Gems’s play is a bright, naturalistic, observant comedy that, I presume, tells it like it is. It is written with a glancing lightness worlds away from the grisly gaiety of those all-girl TV sitcoms, and Nancy Meckler’s production has an eye for simple, behaviourist detail I haven’t seen since Peter Gill’s New York production of Fishing.

Vautrin

Citizens theatre, Glasgow, 10 October 1977

What other company but the Glasgow Citizens would have had the chutzpah to revive Vautrin, a play by Honoré de Balzac that has not been seen since its ill-fated Paris premiere in 1840? Having chosen to revive it, what other company would have been able to hit the right note of opulent romantic melodrama?

Coriolanus

Royal Shakespeare theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, 21 October 1977

Terry Hands’ production of Coriolanus at Stratford is staggeringly good. Played on a dark, cavernous stage over which two huge ribbed doors swing on hinges, it combines the imagistic power of continental theatre with a very English respect for actors. The paradox of the production is that Alan Howard, one of our most likable actors, plays Coriolanus, Shakespeare’s least likable hero. But not since Olivier has anyone played the part with such complete understanding of his mental process.

Betrayal

Lyttelton, London, 16 November 1978

Themes, say some critics, don’t matter: what counts is the skill a dramatist brings to his chosen subject. Well the petit-point school of reviewing should have a field night with Harold Pinter’s Betrayal at the Lyttelton since it is full of technical resource. What distresses me is the pitifully thin strip of human experience it explores and its obsession with the tiny ripples on the stagnant pond of bourgeois affluent life.

Winter Journey

Ashcroft, Croydon, 12 September 1979

Clifford Odets’ Winter Journey is a fascinating backstage melodrama that requires incandescent acting to lift it to a higher plane. Allegedly, it got it when Michael Redgrave, Sam Wanamaker and Googie Withers did a legendary production at the St James in 1952. But the present Cambridge Theatre Company version, now on tour at the Ashcroft, Croydon, is competently acted, thinly directed and wretchedly designed. The curtain is lowered between each of the eight scenes, giving one infinite time to read and reread the programme ads for Turkish restaurants, locksmiths and piano-tuners.

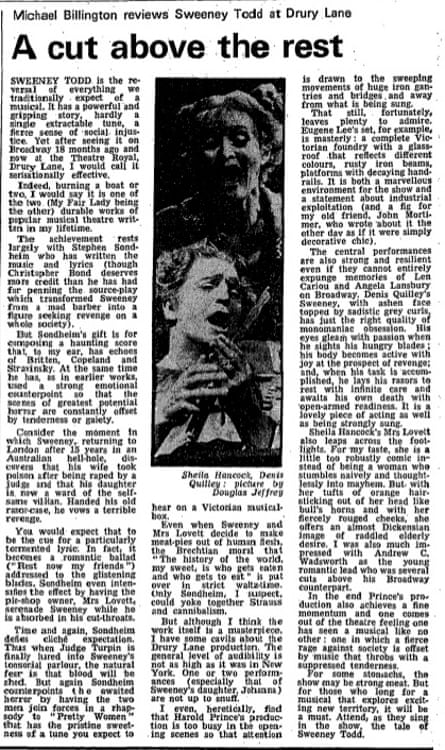

Sweeney Todd

Theatre Royal Drury Lane, London, 3 July 1980

Sweeney Todd is the reversal of everything we traditionally expect of a musical. It has a powerful and gripping story, hardly a single extractable tune, a fierce sense of social justice. Yet, after seeing it on Broadway 18 months ago and now at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, I would call it sensationally effective. Indeed, burning a boat or two, I would say it is one of the two (My Fair Lady being the other) durable works of popular musical theatre in my lifetime.

Cats

New London theatre, London, 12 May 1981

An exhilarating piece of total theatre that demolishes several myths at one go: that the British can’t get a musical together, that our dancers are below American standard, and that musicals with a literary source always dilute their origins. What is heartening is the way the poems are integrated into the occasions. Thus Gus the Theatre Cat (beautifully played by Stephen Tate) is seen as a wistful, white-haired Victorian relic dreaming of palmier days. He is then transmogrified (or transmoggified) into Growltiger, the cutlass-bearing Pirate cat.

Noises Off

Lyric Hammersmith, London, 25 February 1982

Michael Frayn’s play is not simply a machine for creating laughs. It is about the booby-trapped minefield of theatre itself in which one false move, one missed cue, can destroy a carefully created fiction. In one sense, it panders to our sadistic delight in things that go wrong; in another, it is a very intelligent joke about the fragility of all forms of drama.

Aunt Mary

Donmar Warehouse, London, 25 June 1982

Not believing that pain-racked evenings are good for the soul, I am delighted to report that the reopened Donmar Warehouse has highly comfortable, well-raked purple seats, a foyer bar and even a portable interval drinks trolley. The new regime’s opening choice is Pam Gems’ Aunt Mary, which confirms the amiable impression it made on me when I first encountered it as an RSC reading. It may not blaze like a comet, but it is a perfectly decent, compassionate if slightly quirky play (like the work of a Brummagem Tennessee Williams).

Top Girls

Royal Court, London, 9 February 1983

What I admire about Caryl Churchill is that she is not unafraid of downright passion (the rarest commodity in modern British theatre). Having taken us all round her subject, in the final scene Ms Churchill gives us an eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation between Marlene, the one who got away, and her trapped East Anglian sister. And, without spoiling the denouement, it is fair to say that Ms Churchill proves that both sisters are in different ways deprived and that some things are bigger than blood ties.

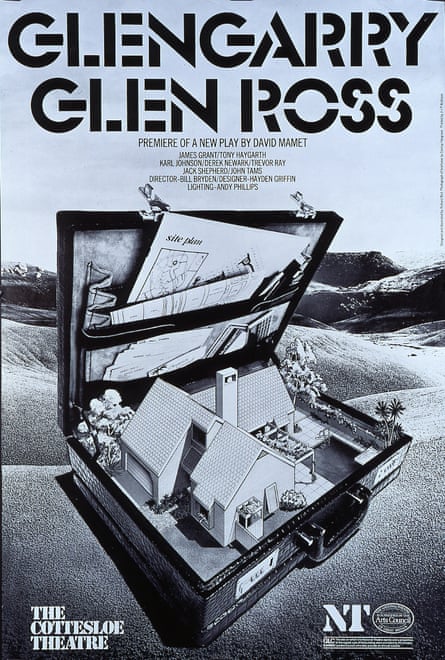

Glengarry Glen Ross

Cottesloe, London, 22 September 1983

The play is filled with the spiralling obscenity and comic bluster of real-estate salesmen caught off guard; yet underneath that there is fear and desperation. Mamet says that he admires his characters’ pragmatic individualism, but to me the piece comes across as a chillingly funny indictment of a world in which you are what you sell.

Death of a Salesman

Broadhurst theatre, New York, 6 April 1984

What is remarkable about Dustin Hoffman’s performance is that it captures all of Willy’s devouring insecurity. “I still feel kind of temporary about myself,” says Willy at one point, and Hoffman presents us with a man who in his sad 60s still doesn’t quite know who he is.

Mrs Gaugin

Almeida, London, 5 June 1984

Style is stronger than substance in Mrs Gauguin: the second production of the new Almeida Theatre Company and an attempt to redeem the reputation of the painter’s wife, Mette Sophie Gad, given a bad press by Maugham in The Moon and Sixpence. Helen Cooper’s script, however, is little more than a series of quick, data-starved, impressionist sketches fleshed out by Mike Bradwell’s visually elegant production.

Saved

Royal Court, London, 21 December 1984

Edward Bond’s Saved returns to the Royal Court in a very fine production by Danny Boyle that brings out more clearly than previous versions the play’s savage humour and tenuous optimism. Nineteen years ago, critics and audiences were understandably poleaxed by the notorious scene of baby-stoning violence. But, while that remains as stomach-turning as ever, it is by no means exploitative or Bond’s final statement on the human condition.

Henry V

Barbican, London, 18 May 1985

Kenneth Branagh’s Henry confirms the good impression he made in Stratford: he combines boyish vulnerability with moral gravitas. I’m not sure he would be capable of the brutalities threatened before Harfleur, but it is an immensely appealing and well-spoken performance. Ian McDiarmid’s Chorus (looking like an RAF bomber pilot) is vocally tricky but rivetingly sardonic, and there is good work from Nicholas Woodeson, who makes the Dauphin a nervous peacock, and from John Carlisle as the Archbishop of Canterbury, who puts the case for war with desperate ingenuity. But then he (and this is one of the production’s major points) doesn’t have to endure the horrendous reality.

Macbeth

Royal Lyceum, Edinburgh, 26 August 1985

The dominant image of Yukio Ninagawa’s production, often seen through a transparent, latticed screen, is cherry blossoms in full bloom. To us, the cherry blossom symbolises beauty; to the Japanese it also signals danger and fear. Thus Banquo is murdered not in the usual stygian darkness but in full light under a cherry tree while putting up the heroic fight expected of a samurai. And Birnam Wood is not the usual set of tatty Babes in the Wood branches but a whole series of ambulatory trees. Throughout, the falling blossom also betokens time passing and the transitoriness of earthly things.

Shirley

Royal Court, London, 1 May 1986

There are echoes here of A Taste of Honey and a midweek telly soap opera. But what gives the play a distinctive tone is Ms Dunbar’s refusal to moralise about her characters: Shirley is seen as neither good nor bad but simply the product of a live-for-now culture. The play neither wags its finger nor buttonholes us with argument. But it is not hard to deduce from it a pretty scathing vision of modern urban life in which men and women see each other as instinctive enemies, relationships are defined by appetite, and escape routes are sought in glue-sniffing by the young and Malibu pineapples by the middle-aged.

Romeo and Juliet

Royal Shakespeare theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, 10 April 1986

As Benvolio arrives on a motorbike and Tybalt turns up in the Veronese square in a low-slung red sports car, it becomes impossible not to dub this the Alfa Romeo and Juliet. Michael Bogdanov has set the play unequivocally in Verona 1986. The result is hip, cool, clever and witty; a painless revitalisation of a play that, for my money, never lives up to its advance publicity as a great love-tragedy and that depends too much on the faulty postal service between Verona and Mantua.

Pour un Oui

Institut Francais, London, 20 January 1987

Nathalie Sarraute excavates, with a good deal of wit, the thoughts that lie between words and the capacity of lifelong relations to be ruined by a momentary inflexion or sudden pause. Read beforehand, the text seemed a bit flat. As played by Jean-Francois Balmer and Sami Frey with enormous emotional variety, it takes off.

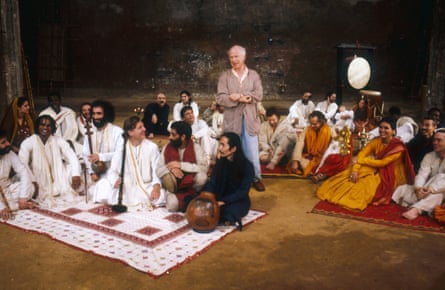

Mahabharata

Zurich, 18 August 1987

“We’re going to spend the night together.” So Peter Brook roguishly told a thousand people gathered on Saturday in a large boathouse on the edge of Zurich’s famous lake. The occasion was the premiere of the English-language version of The Mahabharata. Our communal one-night stand began around eight o’clock on a warm summer’s evening. It ended sensationally 11 hours later with the revelation that the back wall of the boathouse was like a large movable blind, which was slowly lowered to reveal a dazzling morning sun. Even Nature now appears to be directed by Peter Brook.

Uncle Vanya

Vaudeville, London, 26 May 1988

Michael Gambon has inherited Ralph Richardson’s ability to exist in two dimensions at once. Half the time he seems to be living in a private dream: there is a magnificent moment when he is accused of being drunk and cries, “Possibly, possibly” in a voice so alien and remote it might be coming from a man under hypnosis.

The Love of the Nightingale

The Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, 11 November 1988

This is virtually the last production we shall see at Stratford’s Other Place. It is no longer to be licensed as a theatre and we shall have to wait until the early 1990s for a purpose-built replacement. I once called it the most productive corrugated-iron hut in history, and it is amazing to think of the work that has poured out of it over the last 14 years. I can’t think how Broadway, let alone the RSC, will manage without it. Over the years, it has combined classical and modern work and Timberlake Wertenbaker’s oddly haunting, 100-minute fable looks like an attempt to combine the two.

Hamlet

Leicester Haymarket, 20 September 1989

It’s curtains for Yuri Lyubimov. To be more precise it is one curtain, designed by David Borowsky and apparently woven out of hemp, that is the undoubted star of the Lyubimov Hamlet, which has opened at the Leicester Haymarket before going on a world tour. This curtain can advance, retreat, spin on its axis and send characters hurtling into the grave in a way that evokes the nightmare despotism of Elsinore.

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Barbican, London, 29 November 1991

Scene: a murky pub near the Barbican. Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, two sides of the same critic, have just emerged from the first night of David Edgar’s RSC adaptation of RLS’s chilling novella. They compare notes over a vintage malt.

Dr J: My dear Hyde, a capital evening was it not?

Mr H: No sir, more like a capital offence …

Moby Dick

Piccadilly theatre, London, 19 March 1992

Moby Dick is the latest nail to be driven into the glittering coffin of the West End musical. Lacking logic, style, coherence or sense, it turns Melville’s great Dostoevskyan novel into a campy, vulgar schoolgirl spoof in which lines like, “Three years at sea and still no sign of Dick” signal the level of sophistication. Robert Longden’s concept itself poses a problem that his own production never begins to solve. The idea is that we are watching a black-suspendered, St Trinian’s-style school putting on a homemade version of Moby-Dick, which is a bit like the students of Narkover doing The Brothers Karamazov.

Which Witch

Piccadilly theatre, London, 24 October 1992

One of the West End theatre’s special torments is the religious musical. Over the years I recall such vintage horrors as Thomas and the King (with Queen Eleanor’s memorable cry of “Seize that monk!”), a rock Joan of Arc and Bernadette. To that select band we can now add Which Witch, which seems like Norway’s revenge for all those years of humiliation in the Eurovision song contest. Things start ominously with the Inquisition denouncing women for spiriting away men’s private parts and leaving them dangling over trees. We then find a Roman orphan, Maria Vittoria, being unhappily affianced to a German banker somewhat misleadingly named Anton Fugger. But, since Maria is already deeply in love with her Catholic confessor, Daniel, it’s a clear case of Fugger off.

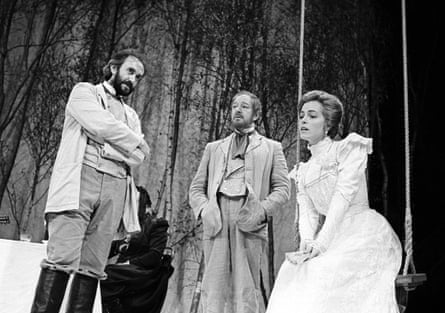

The Tempest

Royal Shakespeare theatre, London, 13 August 1993

Adrian Noble’s biggest problem at the RSC has lain in finding new directors who could handle the main Stratford stage. But Sam Mendes makes the transition from the Swan to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre with a confident, cohesive and strikingly beautiful production of The Tempest: it is the best debut at this daunting address since Noble’s own.

The Piano Lesson

Tricycle, London, 9 October 1993

August Wilson’s decade-by-decade portrait of African-American life reaches Pittsburgh in 1936 – and the key issue is a family’s battle for possession of a symbolic piano. For all the play’s faults, including prolixity and a final lurch into mystical melodrama, you have the feeling throughout the evening that something momentous is at stake. As in Ibsen or O’Neill, the past constantly informs the present.

Old Times

Birmingham Rep, 2 November 1993

“It’s a long way to the coffee table,” said the lady behind me. She had a point. Watching Harold Pinter’s tense, intimate three-hander, Old Times, in the big Birmingham Rep is a bit like seeing Godot in Madison Square Garden. But Bill Alexander’s new production is so beautifully cast and so alert to every nuance of Pinter’s power battle that we soon forget the wide open spaces of the fawn-carpeted circular stage.

The Statement

Watermans, London, 25 January 1994

Although passing tribute is paid to Ruth Rendell and Dorothy L Sayers, the spirit of Marguerite Duras hovers over Helene Pedneault’s The Statement: a six-year-old Quebecois play being presented by The Troupe, in Mark Ravina’s translation, at the Watermans. As so often in Duras, a murder becomes the occasion for an exploration of family relationships, and a certain patience is required before you get your dramatic reward.

Maria Friedman

Donmar Warehouse, London, 31 May 1994

The 85-year-old Elisabeth Welch was in the house the night I went to hear Maria Friedman – By Special Arrangement at the Donmar Warehouse. Fascinating to watch a cabaret legend gazing benevolently at a rising star. For Friedman undeniably has a vocal class, engaging candour and eclectic repertoire that puts her in the great tradition.

The Schoolmistress

Chichester Festival theatre, 8 July 1994

Pinero’s drawing-room dramas are highly revivable. His farces, however, strike me as arch and rickety. And they don’t come much archer than The Schoolmistress (1886), being revived at Chichester Festival Theatre with a fixed and deadly grin. Farce is partly about desperation, but here nothing vital seems at stake.

Leave Taking

National Theatre, London, 7 January 1995

There’s a shining truthfulness about the writing. In particular, Winsome Pinnock shows an extraordinary intuitive sympathy for two different generations. She understands the dilemma of both Enid and Mai, the Obeah woman, who have been deserted by their menfolk and have had to acquire a steely toughness to survive in a strange land. But, equally, she empathises with Viv and Del, who combine an English upbringing with “Caribbean souls” and who have to break free to discover who they really are. It’s a mature, heartbreaking play that deftly combines the specific problems confronting Jamaican families with the universal issue of mother-daughter relationships.

Mojo

Royal Court, London, 20 July 1995

Echoes abound: not only Mamet but Cagney gangster movies and even the recent work of Tarantino. But Jez Butterworth is playing a subtle double game. On the one hand, he himself is influenced by the mythic structures of American movies. On the other, he ironically punctures the way small-time Soho drifters, even in the 1950s, modelled themselves on transatlantic icons: they live in Macmillan’s drab England but they aspire to Mitchum and Mature and are openly derisive when one of their number invokes the wartime team spirit of his Uncle Tommy. Butterworth’s ability to write scintillating dialogue may, at the moment, outstrip anything he has to say. But he understands perfectly how language can be used to camouflage fear or boost ego.

It Could Be Any One Of Us

Stephen Joseph theatre, Scarborough, 21 August 1996

It is a parody of the kind of thriller that used to be staple fare in the reps. Alan Ayckbourn makes amusing play with the cliches of the genre. But his real purpose, as so often, is to write a compassionate anatomy of failure. Indeed, his chief character is a half-shut private eye and deadbeat claims assessor (it is no accident that two of the characters are intending to see Double Indemnity) who could not solve a crossword puzzle. He, of course, decides to take charge of the investigation and, in Jon Strickland’s well-judged performance, he even dons a trenchcoat to quiz the suspects and spins on his heel to finger each of them in turn in the time-honoured tradition of the stock thriller.

Art

Wyndham’s theatre, London, 16 October 1996

When they hand out the acting awards, they are going to have to devise a hydra-headed statuette to cover the blistering performances of Ken Stott, Tom Courtenay and Albert Finney. Add Mark Thompson’s pristine, white-walled set and Gary Yershon’s score, and you have an evening that gives undeniable pleasure. But the real test is whether the play encourages audiences to embrace modern art or reject it. I have an uneasy feeling that Yasmina Reza’s play, for all its manifest cleverness, panders to popular prejudice.

Playing With Fire

Nottingham Playhouse, 3 May 1997

Good theatre often confirms one’s prejudices; great theatre radically alters one’s perceptions. And the remarkable thing about Luc Bondy’s brilliant modern-dress production of Playing With Fire, starring Emmanuelle Béart, is that it totally reinvents Strindberg. In its lightness, wit, eroticism and aestheticism, it resembles nothing so much as an Eric Rohmer movie.

The Cherry Orchard

Birmingham Rep, 29 May 1997

Watching an American adaptation of The Cherry Orchard set in the deep south, Noël Coward famously described it as A Month in the Wrong Country. No one could be so brutal about Janet Suzman’s equally radical version of Chekhov’s play – a co-production between Birmingham Rep and the Market Theatre, Johannesburg – which transposes the action to today’s South Africa. It is an intriguing experiment that throws some areas of the play into high relief, while obscuring others. Suzman never cracks one key problem. Chekhov’s play is a study of a society on the brink of change; in South Africa, the revolution has already happened.

Caravan

Bush theatre, London, 18 November 1997

What better way for the Bush to celebrate its 25-year existence than with a first play by a new writer? Caravan, by Helen Blakeman, yet another graduate of Birmingham University’s playwriting course, bulges with promise: not least because the action is shaped by character, public events and the holiday home that gives the play its title. The setting is a caravan park in North Wales: what we see is the steady disintegration of a Liverpool working-class family in the enforced intimacy of their hideaway.

Haroun and the Sea of Stories

Cottesloe, London, 3 October 1998

What makes a children’s classic? A mixture of adventure and allegory. Of adolescent excitement and adult myth. And the charm of Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories, beautifully staged by Tim Supple in an adaptation by him and David Tushingham, is that it works on so many levels. Behind its picturesque fable lies a passionate plea for imaginative freedom, symbolised on the first night by the author’s liberated presence on stage at the curtain call.

Be My Baby

Pleasance, London, 14 November 1998

Amanda Whittington’s Be My Baby poignantly pictures the painful predicament of institutionalised young mums. Set in 1965, it also reminds us of the stranglehold of official morality even in that supposedly libertarian decade. Whittington focuses on 19-year-old Mary, a pregnant middle-class girl deposited by her mum in the St Saviour’s home. Once the child is born, welfare services will place it with adoptive parents. But the real point is to show how, in the 60s, all classes treated extramarital pregnancy as a guilty secret and how even pop culture nourished the dream of holy wedlock with the perfect partner. One of the most touching scenes shows the girls in the home miming to the Dixie Cups’ insidiously catching hit Chapel of Love.

Easy Virtue

Chichester Festival theatre, 29 July 1999

Who does the young Noël Coward remind me of? In a strange way, John Osborne. Both were iconoclasts nostalgic for a world they attacked, both were headline celebrities with a private belief in the work ethic. And, for proof of Coward’s internal contradictions, you have only to see his 1924 play, Easy Virtue, given a rare and largely successful revival by Maria Aitken at Chichester.

King Lear

Royal Exchange, Manchester, 17 September 1999

Tom Courtenay is undeniably better at conveying the anguish of suffering than the arrogance of power; in that sense, he is more sinned against than Sinden. In the opening scene, played in what looks like a formal Renaissance court, one misses the “great rage” that should animate Lear. Courtenay establishes Lear’s shuffling, slow-speaking antiquity, but he reacts to Cordelia’s silence and Kent’s candour with a wry puzzlement rather than a tyrannical wrath. Even the fearful curses rained down on Goneril’s womb seem more rhetorical than heartfelt. The turning point comes with Lear’s great attack on superfluity: “O, reason not the need.” Suddenly, Courtenay’s voice acquires a pitiable desperation that pricks one’s tears and, as Lear declines into madness, so the actor grows steadily in stature.

The Lion King

Lyceum, London, 21 October 1999

The show’s undoubted appeal lies in Richard Hudson’s scenic design and the masks and puppetry of Julie Taymor and Michael Curry. Taymor, as director, is the organising visual spirit behind the show, and she produces a child’s garden of delights. But even here one notices how much she borrows from the international theatrical language. When the lions demonstrate grief over the death of their king, Mufasa, by producing ribbons of white silk from their eyes, the effect is pure Peter Brook. Taymor has shopped around shrewdly; but, as with the music, what we have is an artful synthesis of international styles rather than something African.

Arcadia

Chichester Festival theatre, 24 August 2000

Tom Stoppard’s play is many things: part satire, part detective story (who was the hermit who died in the grounds of Sidley Park?), part debate about determinism and free will, part celebration of ungovernable human curiosity in the face of the running down of the universe. The play is a fantastically ingenious construct, but it lacks a strong internal dynamic, and Peter Wood’s production, explanatory rather than emotional, makes you aware of the lack of narrative propulsion. The one genuinely moving moment comes when Thomasina’s tutor, responding to her lament over Caesar’s burning of the Alexandrian library, argues that whatever is historically lost is recovered in the long march of humanity.

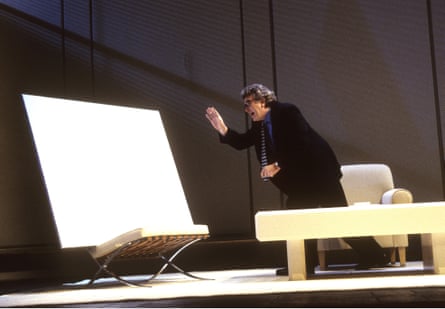

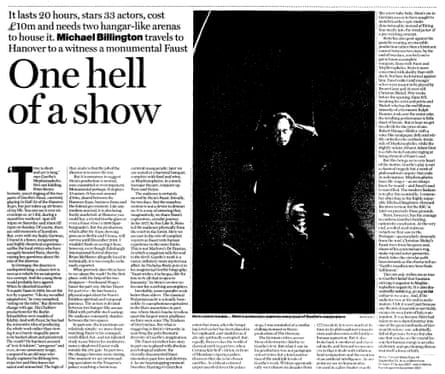

Faust

Hanover Expo, 2 September 2000

“Time is short and art is long,” says Goethe’s Mephistopheles. He’s not kidding. Peter Stein’s historic, uncut staging of the two parts of Goethe’s Faust, currently playing in Hall 23 of the Hanover Expo, has just taken up 20 hours of my life. You can see it over six evenings or, as I did, during a marathon weekend: 3pm till 10pm on Saturday and 10am till 11pm on Sunday. The action is divided between two hangar-like arenas filled with portable steel seating: the audience constantly shuttles between the two spaces. The audience is certainly moved by Stein’s Faust: literally, for two days. But the ceaseless motion is not a device to distract us. It is a way of ensuring that, imaginatively, we share Faust’s exploratory, circular journey.

The Circle

Salisbury Playhouse, 12 October 2000

The danger is that this kind of play, written in 1919, elicits a stock response. It boasts french windows, a stately drawing room, Georgian furniture: all the things young dramatists have fought against. Study the play closely, however, and you see that Somerset Maugham is offering a waspish portrait of upper-class manners.

The Accused

Theatre Royal Haymarket, London, 6 December 2000

Jeffrey Archer, in the character of a doctor on trial for wife murder, was last night proclaimed guilty by a majority audience vote of 333 to 254. A more considered verdict might be that, as the play’s author, he is also culpable of taking West End theatre back about 50 years by creating a cardboard courtroom drama.

Blasted

Royal Court, London, 5 April 2001

Five years ago, I was rudely dismissive of Sarah Kane’s Blasted. Yet watching its revival last night I was overcome by its sombre power. So what has changed? The space, the design, the lighting, the cast and James Macdonald’s production are all radically different. But, above all, one sees the play through the perspective of Kane’s tragically short career and her obsession with love’s survival in a monstrously cruel world.

Frozen

Cottesloe, London, 4 July 2002

The force of Bryony Lavery’s play lies in its ability to change hearts and minds. It never mitigates the horror of child killing, but it makes us understand Agnetha’s argument that physical damage to the brain, rather than inborn evil, prompts serial murder. In an extraordinary scene, Nancy confronts Ralph in his cell and offers him a forgiveness far more fatal than a distant, cold-blooded revenge. I still think there are contradictions within Lavery’s argument: on one level she is out to prove the predictable banality of the killer, yet Agnetha describes Ralph as “mesmerising like a rattlesnake”. And, while showing Ralph as methodically calculating, Lavery brushes aside the idea of moral responsibility. But, in a world filled with tabloid hysteria, Lavery’s play comes across as a refreshing draught of sanity.

Sanctuary

Loft, Lyttelton, London, 31 July 2002

I admire Tanika Gupta for using the stage to rub our noses in global reality. There is a graphic description, for instance, of the killings in Rwanda and of the butchery of 3,000 Tutsis seeking sanctuary in a church. And Kabir feels he is haunted by Satan for having failed to protect his wife from a group of rapacious Indian soldiers. Gupta’s play may not always be fair, but it touches a nerve when it suggests that, in our snug little island, we are either ignorant of or indifferent to the world’s suffering.

Mother’s Day

Lyric Studio, London, 21 September 2002

Unironic optimism is a rare quality in modern drama. But Courttia Newland’s Mother’s Day, enthusiastically put across by the multicultural Post Office company, posits a Britain in which the nuclear family thrives, racial harmony is easily achieved and local councils act with enlightened beneficence. By the end, I was almost prepared to believe in Santa Claus.

The Mob

Orange Tree, London, 9 September 2003

The stock argument against John Galsworthy is that, in plays like Strife and Justice, he suffered from a neutralising impartiality. But here his passions are sufficiently aroused for him to allow his hero an unnerving Coriolanus-like contempt for the mob; and even though Galsworthy shows a measure of sympathy for More’s wife, whose brother is called to the front, he also suggests that she shamelessly uses sexual blackmail to break her husband’s militant pacifism.

The Sugar Syndrome

Royal Court, London, 21 October 2003

This first play by 22-year-old Lucy Prebble has many of the virtues – and some of the faults – you expect in early work. It tackles tricky subjects, such as paedophilia and teenage psychological disorders, with unselfconscious candour: at the same time, having outlawed instant moral judgment, Prebble can’t quite determine what to put in its place. Her purpose may be unclear but she has an instinctive playwright’s gift for grabbing your attention and compelling sympathy for damaged people.

Hamlet

Old Vic, London, 28 April 2004

Trevor Nunn’s boldest decision is to cast Ben Whishaw, in his early 20s, as Hamlet. With his hollow cheeks, spindly frame and nail-biting intensity, Whishaw makes a compelling figure. In his feigned madness, he reminded me of a scuttling, manic Danish Mr Bean. There are several moments, as when Hamlet tells Gertrude that at her age “the heyday in the blood is tame”, when Whishaw profitably reminds you of Hamlet’s callowness. But what this Hamlet lacks is irony, reflectiveness and any sense that he poses a real physical danger to Claudius.

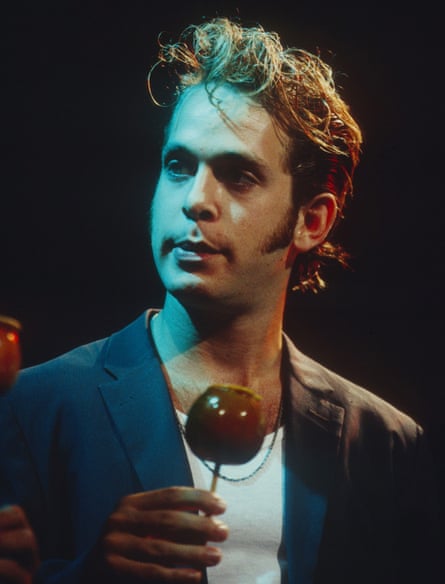

The History Boys

Lyttelton, London, 19 May 2004

What is astonishing is how much territory Bennett manages to cover: the teaching and meaning of history, inflexible and imaginative approaches to education, and the idea, as in Forty Years On, that a school has the potential to be a metaphor for English life. It is no accident that the play is set in the 80s, when the arguments between beleaguered humanism and pragmatic functionalism were at the very height. The play is also blissfully funny, but behind the almost ceaseless laughter lies a hymn to the joys of language, intellectual exploration and inspirational educators.

Don Carlos

Crucible, Sheffield, 4 October 2004

The triumph of Michael Grandage’s production and Christopher Oram’s design lies in their visualisation of Schiller’s ideas. A swinging thurible, a prison-like court with high, barred windows, even the menacing hiss of the ladies-in-waiting’s fans all tell us that we are in a world of religious and political tyranny – a point underlined by Mike Poulton’s translation, where Philip announces: “The instrument God places in my hand is terror.” But Grandage also captures the subversive eruption of feeling in this crepuscular hell: at one point Richard Coyle’s neurotic Don Carlos beats against the court doors like a trapped animal, and his simultaneous passion for Posa and the queen implies a state of Hamletesque sexual confusion.

Hedda Gabler

Almeida, London, 17 March 2005

The character of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler is infinitely various. In the past we’ve had melodramatic Heddas, neurasthenic Heddas, socially superior Heddas. But, in Richard Eyre’s fine new production, Eve Best gives us a dazzlingly ironic Hedda: one aware of life’s absurdity and viewing it with a mixture of dark humour and angry exasperation.

You Never Can Tell

Theatre Royal, Bath, 27 August 2005

I am staggered by our current indifference to Shaw: when, for instance, did the National Theatre last revive one of his plays? Peter Hall almost single-handedly keeps the Shavian flame alight; and his revival of this 1897 comedy captures perfectly its Mozartian ability to handle serious issues with an airy lightness and grace.

A Right Royal Farce

King’s Head, London, 2 August 2006

Last year Toby Young and Lloyd Evans wrote a mildly amusing farce, Who’s the Daddy?, about the shenanigans at the Spectator. Now they have tried to repeat the format with the royal family, and the result is an evening of desperation. Even to summarise the inane plot requires a heroic act of will … Young and Evans struck lucky with their Spectator skit, but this play suggests they don’t know their farce from their elbow.

War Horse

Olivier, London, 18 October 2007

Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris recreate the kaleidoscopic horror of war through bold imagery, including the remorseless advance of a manually operated tank, and through the line drawings of Rae Smith projected on to a suspended screen. Admittedly, the performers are somewhat eclipsed by the action, but Luke Treadaway, as the tenacious Albert, and Angus Wright, as the sympathetic captain, make their mark. The joy of the evening, however, lies in the skilled recreation of equine life and in its unshaken belief that mankind is ennobled by its love of the horse.

The Brothers Size

Young Vic, London, 14 November 2007

Tarell Alvin McCraney is a graduate of Yale School of Drama and what he has done in this study of two black Louisiana brothers is draw on “elements, icons and stories from the Yoruba cosmology”. In practice, this means that the action combines ritual and realism, and that the language takes the form of a heightened prose-poetry. Without doubting McCraney’s talent, I feel that the result is a conscious literary artefact. What I wouldn’t deny is that it comes thrillingly alive in performance.

Glaspell Shorts

Orange Tree, London, 9 April 2008

It was the deceptively named Trifles, written in 1916, that established Susan Glaspell’s reputation. Set on a remote farm where a murder has taken place, it shows female observation triumphing over male obtuseness. While an attorney and sheriff blunder around, their wives discover the real clue to the crime in an empty cage, a strangled songbird and a badly sewn quilt. With the deftest economy, Glaspell conjures up a world of solitude, despair and imprisonment where the women acknowledge their share of guilt.

Fast Labour

West Yorkshire Playhouse, 25 April 2008

The play reminds us of our own complicity in the migrant labour industry: as someone points out, the British want their last-minute iceberg lettuce in March without questioning how it got there. Steve Waters’ twin-focus technique allows the migrants to drop their fractured English, signalling a return to their native tongue, and exchange wickedly subversive thoughts about their inherited world.

Her Naked Skin

Olivier, London, 2 August 2008

Rebecca Lenkiweicz’s method is to start with a wide-angled shot and then gradually focus on intimate relationships. Film footage of Emily Davison’s sacrificial gesture at the 1913 Derby is followed by a sketch of male political intransigence over female suffrage. But Lenkiewicz’s real concern is to show how female militancy transcended class and sexual convention. Lady Celia Cain, trapped in a loveless marriage, is erotically drawn to Eve, a young suffragette machinist. Passion and politics coalesce as they pursue an intense affair, but the question Lenkiewicz obliquely raises is whether liberation is more easily achieved from a position of social privilege.

Imagine This

New London theatre, 20 November 2008

They said it couldn’t be done: a musical about the Warsaw ghetto. And, now that I’ve seen it, I know that they were right. If this show ultimately fails, it is not for want of trying, but because of the discrepancy between form and content. The romantic sentiment and uplift inherent in the musical sit uneasily with a story of not just heroic resistance but starvation, suffering and the death of more than 100,000 Polish Jews.

Death and the King’s Horseman

Olivier, London, 9 April 2009

Rufus Norris’s production, with the aid of Katrina Lindsay’s spectacular design, moves assuredly from the teeming world of a raffia-filled market to the play’s elemental conclusion. There are sterling performances from Nonso Anonzie as the horseman, Kobna Holdbrook-Smith as his son, and Claire Benedict as the market leader. One emerges dazzled but also disturbed by Soyinka’s ideas: in particular, the unfashionable notion that death can be seen as a triumphant entrance rather than a tragic exit.

Funny Turns

Hull Truck, 30 April 2009

In these recessive times, a new theatre is as rare as snow in June. And, in moving from an old converted backstreet Methodist church into a spanking new space in the town centre, Hull Truck has got itself a dazzler. What strikes me is the value for money of the £15m venue: it boasts a 440-seat main house, a 135-seat studio and wide public spaces that use glazed brick and steel. The wraparound stage has echoes of the former Spring Street building, and Funny Turns, written and directed by John Godber, shows his familiar optimistic championship of society’s underdogs. Even if it doesn’t have the instant mythic appeal of Bouncers and Up’n’Under, it displays a similar warmheartedness.

It Felt Like a Kiss

Hardman Square, Manchester, 3 July 2009

The last third of the evening is a total letdown. We find ourselves wandering through debris-filled rooms, entering desolate cells, even being pursued down darkened corridors by a masked man clutching a chainsaw. I guess the aim is to show how the American dream turned into a nightmare. But to do it through these fairground shock tactics is an insult to our intelligence. The cant critical word for this kind of thing is “scary”. But what is the point of simply making people jump out of their skins?

The Black Album

Cottesloe, London, 22 July 2009

Hanif Kureishi has turned his own vibrant 1995 novel into a play. The result is a busy, hectic affair that raises all kinds of issues about religious and political faith, fatwas and censorship and the purpose of art. But, as so often with adaptations, you get the bones without the thickness of texture that was part of the original’s charm.

Category B

Tricycle, London, 13 October 2009

The Tricycle certainly thinks big. After its trilogy about Afghanistan earlier in the year, it now comes up with an ambitious three-play season by black writers about the state of Britain. First out of the blocks is Roy Williams with a typically forceful play about prison life that manages to avoid most of the cliches that cling to the genre. Williams’ setting is a category-B jail: the kind that neither the screws nor the prisoners want to end up in. But what he brings out are the uncanny parallels between the institution’s rival power blocs.

Behud (Beyond Belief)

Belgrade, Coventry, 31 March 2010

You can see why Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti had to write this play. It is her response to the notorious events that in 2004 led to her play, Behzti, being withdrawn after mass Sikh protests outside, and even inside, Birmingham Rep. By recreating that traumatic episode in fictionalised form, Bhatti is clearly exorcising her demons and liberating her imagination. The new piece, however, is only intermittently successful as drama.

The Man

Finborough, London 1 Jun 2010

Theatre is different every night, but this new piece by James Graham, which forms the centrepiece of a Finborough festival offering 30 plays in 30 days, takes the idea of flux to Ayckbourn-style lengths. Four actors alternate in the role of Ben (I caught Samuel Barnett). The sequence of events also depends on receipts handed out to the audience as they enter; they are later reclaimed by Ben as he struggles to fill in a tax return and recall a year of London life. The idea of tax receipts as an index to existence is highly original.

The Persians

Brecon Beacons, 13 August 2010

This is site-specific theatre with a vengeance. High up in the Brecon Beacons, in a mock-up village used by the military as a training base, National Theatre Wales is recreating the oldest extant play in western drama: Aeschylus’s The Persians. The combination of the story and the setting, with the sun slowly disappearing over the hills, is overwhelming. We assemble in a square in this deserted military village where the four-strong male chorus is rejoicing in war and announcing: “No one can withstand this tsunami of the Persians in full rage.” We then march up a hill to sit in front of a four-storey house with the front cut away; and there we see, both in live action and on video, the tragedy enacted. There’s a wonderful moment when Atossa arrives in a white car to a blaze of trumpets.

Onassis

Novello, London, 13 October 2010

Martin Sherman has written not so much a play as a part, and it is one that Robert Lindsay fills to overflowing. But, as if to compensate for the emptiness of the dialogue, he is forced to lapse into an Anthony Quinn style of overacting that I’m tempted to dub Exorbitant the Greek. “Stillness always works,” Onassis remarks at one point, but you’d scarcely know it from the restless, larger-than-life performance filled with extravagant hand gestures that Lindsay feels obliged to give. He is a fine actor compelled, by the fundamental lack of drama, to put on a bit of a show.

Racing Demon

Crucible, Sheffield, 18 February 2011

David Hare’s play gets richer with time. Acclaimed in 1990 for its accurate portrait of a Church of England in crisis, it now seems a perfect metaphor for British institutional life. Presented as part of Sheffield’s three-play Hare season, it could be about the tensions inside any hierarchical organisation, from a political party to a national newspaper. What is impressive is Hare’s imaginative reach: his ability to see the virtues, as well as the flaws, in every character.

Frankenstein

Olivier, London, 24 February 2011

Benedict Cumberbatch’s Creature is unforgettable. “Tall as a pine tree,” as the text insists, he has humour as well as pathos: his naked entry into the world is marked by a totter on splayed feet and, when he moves, it is with a forward-thrusting, angular, almost Hulotesque curiosity. But there is also an epic grandeur about Cumberbatch. As he quotes Paradise Lost, his voice savours every syllable of Milton’s words and when, in outrage at his rejection by the exile’s family, he burns their cottage, he utters a Hamletesque cry of “I sweep to my revenge.” It is an astonishing performance. Miller’s strength, in contrast, lies in his menace. Stockier than Cumberbatch, his Creature makes you believe in the character’s satanic impulse and in his capacity for murder.

truth and reconciliation

Royal Court, London, 6 September 2011

Staged by debbie tucker green herself in the Theatre Upstairs, with the spectators sitting on hard chairs that replicate those endured by the characters, the piece is cryptic, fragmented, unsettling and well acted – especially by Wunmi Mosaku as the Rwandan widow, Petra Letang as the zealous Zimbabwean, and Clare Cathcart as a defiant Northern Irish mother. But, although the play raises the issue of whether truth and reconciliation can be compatible, it feels strangely incomplete. I wanted either to hear the piece again or attend a post-play discussion to learn whether the author’s political pessimism was justified.

Stones in His Pockets

Tricycle, London, 20 December 2011

Marie Jones’s witty conceit is to view the making of a piece of Hollywood-Irish hokum from the perspective of two County Kerry extras: the quintessentially optimistic Charlie and the more jaundiced Jake, lately returned from New York. What Jones does is to skilfully oppose life and art. In the movie, the high-born heroine romantically weds a local lad; in reality, Jake rejects the advances of the gushing American star who pretends to seduce him in order to appropriate his accent. And, while the film offers a rose-tinted vision of Irish life, the truth is that the land is being split up and Jake’s suicidal cousin is the latest victim of both rural decline and the national propensity to dream.

Hay Fever

Noël Coward theatre, London, 27 February 2012

Among the guests there is a peach of a performance from Jeremy Northam as the buttoned-up diplomat quivering with shy lust. His initial, embarrassed encounter with Amy Morgan’s taciturn flapper also proves that Coward, like Pinter, knew the comic value of extended pauses. And Phoebe Waller-Bridge makes something truly memorable of Judith’s daughter whom she plays as a gauche 19-year-old trying strenuously hard to be soigné and sophisticated. But that simply offers further proof that Coward’s 1924 comedy becomes even funnier when played, as in Davies’s fine revival, for its emotional veracity.

The Radicalisation of Bradley Manning

Cardiff High School, Wales, 19 April 2012

Tim Price gives us a vivid picture of Manning’s life and of the contradictory responses that he evokes. But what troubles me is the blurring of fact and fiction. I can easily believe that Manning would have been taught about Welsh radicals, from the Chartist John Frost to Aneurin Bevan. But, in one scene, Manning is asked to enact the role of the 23-year-old Dic Penderyn, who in 1831 led a Merthyr uprising and was publicly executed. Entering into the spirit of the part, the 13-year-old Manning denies that Penderyn was a martyr and says: “I just got caught and blamed for something I didn’t do.” Dramatic licence is here stretched to the utmost in that Price makes the schoolboy Manning utter sentiments that appear to prophesy his present predicament.

London Road

Olivier, London, 13 August 2012

Conventional musicals, even at their best, take us into a world of fantasy. This miraculously innovative show finds a new way of representing reality. Rufus Norris’s production and Katrina Lindsay’s design also deftly evoke the community’s transition from a period of terror to one of entrapment, symbolised by a maze of police incident tape, to restoration, as floral baskets descend from the Olivier ceiling. And an 11-strong ensemble play multiple characters – with Kate Fleetwood, Nick Holder and Nicola Sloane outstanding as leading lights in Neighbourhood Watch. A previous Blythe show about seaside sex workers, The Girlfriend Experience, smacked of condescension. But this one not only explores the way it takes a crisis to engender community spirit but opens up rich possibilities for musical theatre.

My Life After

Corn Exchange, Brighton, 27 May 2013

The Brighton festival’s theatre programme ended with this extraordinary import from Argentina in which five actors recalled, with the aid of photos, letters, home movies and old clothes, the lives of their parents. Conceived and directed by Lola Arias, the show offered a compelling mix of personal memories and – since the actors were all born around the time of the 1976-83 dictatorship – a mosaic of modern Argentinian history. I suspect Arias is an admirer of the Brazilian pioneer Augusto Boal, whose “theatre of the oppressed” dramatised communal issues. Here, the big question is how the actors either live up to the radicalism of a previous generation or, in one case, live down its collusion with dictatorship.

Chimerica

Almeida, London, 30 May 2013

“Chimerica” was a term coined by economist Niall Ferguson to indicate the global dominance of the dual country that is China and America. But Kirkwood’s play highlights the sharp differences, as well as the similarities, between the twin superpowers. In America, Joe’s bolshie individualism as a photographer who records world events is ultimately celebrated; in China, Zhang Lin, who has already suffered for his involvement in the Tiananmen protests, pays a heavy price for inciting unrest. Kirkwood goes further in examining the nature of capitalism in both countries. China may be open to western investment and apparently enthralled by its products; at the same time, Joe’s girlfriend, Tessa, in a brilliant presentation speech to her clients, explains that the only way into its markets is to understand that China is a country that values the supremacy of its culture.

Handbagged

Tricycle, London, 2 October 2013

Buffini’s brightest idea is to double the central roles. So we get an older and younger Queen, respectively known as Q and Liz. Equally, we get an older and younger Thatcher, identified as T and Mags. Add in two male actors playing 17 other roles, ranging from Kenneth Kaunda to Rupert Murdoch, and you have what sounds like a recipe for confusion. In fact, Buffini’s device gives the whole evening a buoyant, meta-theatrical playfulness. The older Q spends much of the play trying to hustle the action along in order to get to the interval. And the two Thatchers, while consistent in their detestation of socialism, often lapse into a good cop/bad cop routine that says a lot about the late PM’s contradictory techniques.

Punishment Without Revenge

Theatre Royal, Bath, 22 October 2013

This is the real deal: an unqualified masterpiece by Lope de Vega that, in Meredith Oakes’s excellent new translation, forms part of Bath’s Spanish Golden Age season. Since Lope’s 1631 play deals with the guilt-racked love between a young woman and her stepson, one is inevitably reminded of Euripides’s Hippolytus and Racine’s Phedre in its moral intricacy. However, Lope’s play is the equal of its twin rivals – and indeed, in some ways, far better. This is a multilayered play that touches on numerous themes, from the power of theatre to poisoned inheritances. It gets a first-rate production from Laurence Boswell, which is physically spare yet implies sumptuousness. Much of that is down to Mark Bailey’s sets and costumes, with their silver thrones and sable doublets.

Ciphers

Everyman theatre, Cheltenham, 23 October 2013

Even if Dawn King’s play is not as original as Foxfinder, it is clearly the work of a natural dramatist who knows how to generate suspense. Blanche McIntyre’s production and James Perkins’ design, based on sliding white screens, also have a pristine purity that contrasts neatly with the murkiness of a world in which human beings are disposable. Keenan doubles beautifully as both the enigmatic Justine and her upfront sister, and there is strong support from Jhutti as both a community worker and an adulterous artist, and from Bruce Alexander and Shereen Martin as figures who, in both sections of the plot, are pulling the strings. The result is an intelligent puzzle play in which, rather as in Macbeth, nothing is but what is not.

Ellen Terry With Eileen Atkins

Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, London, 21 January 2014

Actors are often the sharpest judges of Shakespeare: a point proved by Ellen Terry, who in 1910 started touring a series of informal lecture-demonstrations on Shakespeare’s characters. Eileen Atkins has now adapted them into a 75-minute show that offers the delirious pleasure of seeing one great actor inhabiting the mind and spirit of another. Atkins possesses not just an immaculate technique but an imagination that allows her effortlessly to transcend the limitations of age and gender. If the BBC does not instantly send a film crew to record this masterclass in the art of acting, I shall go and chain myself to the portals of Broadcasting House in protest.

Twelfth Night

Everyman, Liverpool, 13 March 2014

Adam Levy’s white-suited, self-dramatising Orsino repeats the play’s opening word, “If”, three times as a prelude to a visual coup introducing the shipwrecked Viola. As scholar Michael Dobson has pointed out, the whole play seems to take place within a conditional clause, asking “what if there were a country such as Illyria?” Gemma Bodinetz seizes on that idea to present us with a series of interlocking fantasies in which people lose their sense of self. There’s a telling moment when Jodie McNee’s disguised Viola, asked by Natalie Dew’s Olivia “What are you? What would you?”, looks totally flummoxed as if she herself is unsure.

This May Hurt a Bit

Octagon, Bolton, 27 March 2014

Since the NHS is never out of the headlines and directly affects most of us, our theatre has long been crying out for a new play on the subject. And, while Stella Feehily’s piece, co-produced by Out of Joint and the Octagon, is unapologetic agitprop on behalf of a beleaguered service, it makes its points most effectively when it captures the mix of care and chaos you find in wards up and down the country.

Yellow Face

The Shed, London, 12 May 2014

David Henry Hwang uses the satirical format to ask what it means to be classified by ethnicity, and also to invoke the xenophobic persecution of Chinese-Americans in the late 1990s. Behind the laughter, this is a probingly political play that tests the validity of Hwang’s optimistic assertion that “it doesn’t matter what someone looks like on the outside”. Alex Sims’s bracing production pursues its ideas with quickfire vigour. It’s a peach of a play, using theatre as a metaphor for life.

Ballyturk

Black Box, Galway, 21 July 2014

As so often in Enda Walsh’s plays, the main characters inhabit a hermetic world – almost a womb without a view. In this case, they are two men, simply identified as One and Two, who pass the time in speeded-up, silent-comedy rituals and speculating about daily life in an imagined Irish town called Ballyturk. But when the character Three turns up, he not only breaks up the partnership but invites one of the duo into the outer world, en route to inevitable extinction. It is not the last surprise Walsh springs, but it is as if Beckett’s Godot had unexpectedly materialised.

The James Plays

Festival theatre, Edinburgh, 11 August 2014

The main thing to say about Rona Munro’s plays is that, while telling us a lot about Scottish history from 1421 to 1488, they are also full of topical resonance. You see this especially in the opening play, The Key Will Keep the Lock. It shows James Stewart, after being kept a prisoner by the English for 18 years, finally assuming the Scottish throne that was rightfully his. As he does so, James McArdle’s wonderfully nervous king gives a speech to his aggressive nobles in which he pours scorn on England’s financial predatoriness and claims that a future Scotland “will be assaulted but it will never be broken”. It’s a good line that could easily be appropriated – and probably will be – by Alex Salmond.

The Apple Family Plays

Brighton Dome Corn Exchange, 5 May 2015

British drama tends to be driven by politics and American by relationships. That, at least, is what we assume. Such generalisations are blown apart by Richard Nelson’s extraordinary quartet of plays, which dominated the opening weekend of this year’s Brighton festival. Lasting close to seven hours in total, the plays use the crises within a single family to explore the larger confusions of liberal America. What is striking is how much ground Nelson covers: hope and disillusion, individual and collective memory, and the need to acknowledge the past without being possessed by it.

The Trial

Young Vic, London, 29 June 2015

Someone must have had it in for Michael B. He was dozing peacefully at home when a knock came at the door. Two men appeared, telling him he had to attend a new production of Kafka’s The Trial. “But I’ve done nothing wrong,” he protested. “I’ve seen Steven Berkoff’s version on stage. I’ve also seen a film directed by Orson Welles and another written by Harold Pinter.” He was forcefully told that was not enough. This time everything would be radically different. Watched by his guards, he arrived at the theatre to find a crowd excitedly milling around. To get to the auditorium people were led down long corridors and admitted through keyhole-shaped doors. Once inside, Michael B was seated on a judicial bench and at first astonished by what he saw.

The Skriker

Royal Exchange, Manchester, 6 July 2015

When Caryl Churchill’s collaborative fantasy was first seen in 1994, it was regarded as bafflingly obscure. Aspects of it remain difficult but, watching the magnetic Maxine Peake, it becomes clear that the play offers, among other things, a vision of climate catastrophe we can all understand. In some ways, Churchill’s play is like a darker version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in that it shows a collision between mortal and immortal worlds. The big difference is that Churchill’s skriker, a shape-shifting, ancient fairy, is chillingly visible, unlike Shakespeare’s Puck, to the two teenage girls whom she haunts and pursues.

Medea

Gate, London, 10 November 2015

Euripides’ Medea has achieved such mythical status it is subject to endless variations. But, where Rachel Cusk’s new version at the Almeida cheats us of the cathartic climax, this radical update by Kate Mulvany and Anne-Louise Sarks, that originated at the Belvoir Sydney, does not duck the story’s horror. Its big idea is to see the action from the perspective of the heroine’s two children and the effect is as startling as Tom Stoppard’s notion of viewing Hamlet from the vantage point of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

Look Back in Anger

Derby theatre, 9 March 2016

You may go expecting a museum piece. What is startling is that John Osborne’s play, intimately based on his experiences as a married actor at Derby rep – and now celebrating its 60th anniversary – survives due to its unremitting emotional intensity. Director Sarah Brigham has also had the wit to precede it with an hour-long mono-drama by Jane Wainwright that charts the reaction of a gutsy, modern working-class woman to life’s baffling disappointments. Osborne’s play was initially hailed as a vital social document. It says a lot about the class-ridden culture of mid-50s Britain and paints a still-resonant picture of a younger generation educated but with nowhere to go. However, what keeps the play alive is its scorching, Strindbergian portrait of a failing marriage.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night

Bristol Old Vic, 30 March 2016

Timing matters with Eugene O’Neill as much as it does in a Wagner opera. I suspect Richard Eyre is seeking to contrast the brisk allegro of the play’s opening with the long adagio of its tragic end where the four members of the Tyrone family confront the appalling truth. But too often the tempo is unvaried, so that we miss the almost comic pattern of accusation and retraction that afflicts all the characters. When James Tyrone, a celebrated actor who sold out to commercial success, recites Shakespeare and his tubercular son Edmund recites Baudelaire, we should also feel them dwelling on the consolations of poetry rather than rushing through the speeches as they do here.

Doctor Faustus

Duke of York’s theatre, 26 April 2016

The idea of media stardom as a trick of the light is now a truism, and Lloyd’s production is forced to work overtime to give it purchase. We get lashings of sex and violence as well as an awkward collision of the two when Faustus invokes Helen of Troy who appears in the shape of the adoring Wagner and whom he proceeds to stab and rape. The lead actor acquits himself well in the circumstances. Given that he is obliged to bare his buttocks and parade in bloodied boxer shorts, I was tempted to dub him “off-with-your-kit Harington”. But he is much more than a TV icon and, when the production allows him, he gives us a sense of Faustus’s flailing despair.

Bitches

Finborough, London, 18 August 2016

Bola Agbaje has written a number of very good plays about different aspects of cultural identity. She has now come up with a new piece for the National Youth Theatre about two female pals – black Funke and white Cleo – who dedicate their energies to a music-and-chat vlog, but who, off camera, reveal their deep divisions. In exposing the potential dangers of a faith in new technology and the transcendent power of video, Agbaje makes a shrewd point that absolves her from the charge of vlogging a dead horse.

The Rover

The Swan, Stratford-upon-Avon, 16 September 2016

Even if Loveday Ingram allows no innuendo to go unstressed, she successfully steers us through Aphra Behn’s multiplying subplots and allows the action to grow, with the aid of Grant Olding’s fizzing score, out of a society in a permanent state of fiesta. Joseph Millson, making his entrance swinging on a rope like a Restoration Errol Flynn, plays Willmore excellently as a shameless rakehell whose sexual rapacity is offset by a boyish charm. You may not approve of him but you can’t help liking him.

Barber Shop Chronicles

Dorfman, London 8 June 2017

Bijan Sheibani’s exuberant production begins and ends with a party in which audience members dance with the cast or even go on stage for a quick trim. That seems entirely in keeping with the spirit of Inua Ellams’ invigorating play, which shows how barbers’ shops, run by and catering for African men, combine the roles of pub and political platform, social centre and soapbox. It makes the average white British male’s belief that you simply go in for a haircut look decidedly dreary.

Julius Caesar

Storyhouse, Chester, 26 June 2017

As the audience assembles in the foyer, pro-Caesar supporters emerge bearing banners saying: “Make Rome great again.” Although upbraided by the tribunes, the crowd noisily cheers as cameras record the arrival of their beloved leader. Celebrations continue in the auditorium, where the Lupercalian fertility festival is in full swing and Christopher Wright’s Caesar, to the accompaniment of rock music, poses for selfies and morphs from Donald Trump in Washington to Jeremy Corbyn at Glastonbury.

Gangsta Granny

Garrick, London, 2 August 2017

Ben, the 11-year-old hero, is a reverse Billy Elliot who has a covert wish to be a plumber and abhors his parents’ passion for ballroom dancing. Meanwhile, his lonely old gran, on whom he is deposited once a week, seems boring, smelly and flatulent but turns out to have a hidden life. It all makes for a lively show that prompts self-examination. When I asked my grandson on the way out if he found me smelly and boring, he had the wit to reply that at least I didn’t smell.

Loot

Park theatre, London, 24 August 2017

Michael Fentiman’s production constantly reminds us that Joe Orton’s shock tactics are a way of alerting us to the hypocrisy of a society in which greed, gain and lust are masked by religious piety and veneration for authority. You see this most clearly in the figure of Inspector Truscott, who, while posing as a man from the Metropolitan Water Board, turns out to be a corruptible sadist. Christopher Fulford plays him to perfection as a moustached suburbanite with a manic gleam.

For Love or Money

Viaduct, Halifax, 24 September 2017

Northern Broadsides have made a habit of giving European classics a Yorkshire setting. So it seems fitting that Barrie Rutter’s farewell, at least on home soil, to the company he founded should be a version by Blake Morrison of Alain-René Lesage’s Turcaret. Even if Morrison’s adaptation is unlikely to cause the offence that the original did in France in 1709, it remains a lively satire on capitalist corruption. Morrison shifts the action from Louis XIV’s Paris to a Yorkshire town in the 1920s, but the characters are still propelled by greed. Rose, a young war widow, milks a besotted bank manager, Algy, for all she can while herself being conned by a money-grubbing cousin. But loot is to this play what sex is to La Ronde, in that it forms an endless daisy chain.

The Shadow Factory

NST City, Southampton, 16 February 2018

Howard Brenton seeks to highlight the gulf between a bloody-minded British belief in liberty and the dictatorial necessities of wartime. Even the local engineer forced to execute Beaverbrook’s plans says: “I feel like I’m carpet-bombing my own town.” This leads Brenton into some strange ironies, whereby an aristo who readily hands over her stately home to the Spitfire design team emerges as more instinctively patriotic than the obdurate Dimmock. The play’s vitality, however, springs from its ability to show British resistance to any form of authoritarianism while keeping its roots firmly in Southampton life.

The Last Ship

Northern Stage, Newcastle, 22 March 2018

Having bombed on Broadway, this musical by Sting about the shipbuilding industry is being revived on its native soil with a new book by its director, Lorne Campbell. The only mystery is why the show ever premiered in the US in the first place. It is a deeply British musical that champions Tyneside life and leaves you in no doubt where it stands on Thatcherite economics. It was received, quite rightly, with full-throated acclaim by its Newcastle audience.

Nine Night

Dorfman, London, 1 May 2018

There’s a key moment in Natasha Gordon’s highly impressive debut play when Aunt Maggie leaves the nine-night funeral wake that is part of her Jamaican heritage to go home and watch EastEnders. “Big tings are gawn in the Queen Vic tonight,” she announces. For me, that neatly sums up Gordon’s theme – which is the ability to inhabit two cultures and to acknowledge one’s ancestral past while living fully in the present.

Machinal

Almeida, London, 12 June 2018

Sophie Treadwell’s writing is impressive for how much it leaves out. She doesn’t need to show us every detail of Helen’s honeymoon or home life to make us understand her sense of suffocation. While her dialogue is stylised, Treadwell uses the polyphonic possibilities of theatre to press home her point. From the outset, Helen seems surrounded by “the purgatory of noise”, whether it be the clack of office machinery, the clatter of garbage collectors or the drill that shreds her postnatal nerves. Sound has lately been reduced to an ominous hum in British theatre; in the expert hands of Ben and Max Ringham, it becomes a vital part of the play’s texture.

The Watsons

Chichester Festival theatre, 8 November 2018

I would seriously urge anyone planning to attend Laura Wade’s adaptation of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel, The Watsons, to stop reading now since one of the play’s many pleasures is its capacity to endlessly take us by surprise. We go in expecting a literary exercise and come out having seen a philosophical comedy.

Sweat

Donmar Warehouse, London, 20 December 2018

Lynn Nottage, as she showed in Intimate Apparel, has the capacity to dramatise work. In this breathtaking new play, she tackles the devastating impact of loss of work and of de-industrialisation on modern America. Based on extensive interviews with residents of the rustbelt town of Reading, Pennsylvania, it shows the anger and despair that helped fuel the election of Donald Trump.

Our Lady of Kibeho

Royal and Derngate, Northampton, 17 January 2019

Katori Hall’s virtue is that she puts a complete world on stage, one that embraces a cloistered college, a faith-hungry village and tribal hatred. James Dacre’s production rises to the challenge with the aid of a community ensemble, a Jonathan Fensom set that shows the sun-kissed landscape beyond the hermetic school, and an Orlando Gough score that blends a cappella singing with tingling accompaniments to the girls’ visions.

La Reprise: Histoire(s) du Theatre (I)

Royal Lyceum, Edinburgh, 4 August 2019

I loved this show for its clarity, compassion and curiosity. Director Milo Rau has something of the ability of Ken Loach to ask disturbing political questions, while extending the possibility of the medium in which he works. This show – which, among many others things, portrays the economic depression of a de-industrialised city and proves theatre is a form of inquiry – marks him out as a major talent.

Mary Poppins

Prince Edward theatre, London, 13 November 2019

I was rather grudging in my praise when I first saw this musical in 2004. Richard Eyre’s production, based on the PL Travers stories and the Disney movie and supplementing the Richard and Robert Sherman songs with new ones by George Stiles and Anthony Drewe, was more remarkable for its clinical efficiency than its pulsating joy. Either the show, which has enjoyed a long UK tour, has changed or I have: it now strikes me as rapturously pleasurable.

Pippi Longstocking

Royal & Derngate, Northampton, 19 December 2019

The virtue of the show is that it conveys the spirit of Astrid Lindgren’s books and suggests that Pippi belongs in the great line of rule-breakers from the medieval Till Eulenspiegel to Richmal Crompton’s William. I came out with a smile on my face, which is fortunate since this show marks the end of a chapter in my life as a critic and allowed me to exit stage left happily chuckling.