- India

- International

55 yrs after death, selected works of India’s first PM completed: ‘Nehru was genuinely global, his nationalism inclusive’

It is hoped that the hundred books will be online soon, as there is immense interest in international Libraries. More so, as these are almost the Collected works as very little material has been kept out.

The process of accumulating and sifting through scores of Nehru’s writings, letters and replies, his speeches and other essays began shortly after his death in 1964. But the compilation has taken more than five decades. (Source: Express Archives)

The process of accumulating and sifting through scores of Nehru’s writings, letters and replies, his speeches and other essays began shortly after his death in 1964. But the compilation has taken more than five decades. (Source: Express Archives)

More than five decades after his death, as India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru continues to dominate headlines and elections speeches even today, what he had to say has finally been put together in 100 volumes of his Selected Works, compiled late last year.

The process of accumulating and sifting through scores of Nehru’s writings, letters and replies, his speeches and other essays began shortly after his death in 1964. But the compilation has taken more than five decades.

Historian Prof Madhavan Palat, the second series editor, said, “Nehru was known to be short-tempered, but whatever he wrote was courteous, firm, clearly stating his position without being abrasive. I was astonished at the number of times he explained himself to (Sikh leader) Tara Singh, refuting the latter’s arguments point by point repeatedly, always correctly and exhaustively. Tara Singh was equally civilised.”

On the civility in discourse at the time, Palat said that when E M S Namboodiripad’s Communist government in Kerala was overthrown unconstitutionally and undemocratically, many Communists were summarily imprisoned in 1962. “Yet, their exchanges with Nehru were remarkably dignified – a Communist like Hiren Mukherjee positively adored Nehru. I have found only two persons were rude to or about him, a retired lieutenant general, Nathu Singh by name, and Ram Manohar Lohia (vol. 78, p. 143). But Nehru did not reply to them in the same vein; he preserved his dignity.”

On his eight-year stint as the series editor, Palat said, “By far the greatest challenge initially was to raise the morale of the editorial team and convince them that this was worth doing, and it can be completed.”

Historian Prof Madhavan Palat, the second series editor, said, “Nehru was known to be short-tempered, but whatever he wrote was courteous, firm, clearly stating his position without being abrasive.”

Historian Prof Madhavan Palat, the second series editor, said, “Nehru was known to be short-tempered, but whatever he wrote was courteous, firm, clearly stating his position without being abrasive.”

For about 20 years, he said, editors had been coming and going and the output averaged about one and a half volumes a year. This was raised to five and a half in these final eight years. Interestingly, the speed of work was improved by reducing the staff from eight or more to three. “Of course, that was possible because I was a full-time editor, the first one they had, and I did not take on any other job.”

So, for a historian, were there any surprise in what and how Nehru thought? Palat said: “I think it is conventional wisdom that Nehru was woolly-headed, vacillating, tending to compromise, not tough enough as it were. But as I read through his archives and saw him dealing with crisis after crisis, and the immense diversity of the country, I sensed that these were his strengths. He tried to bring people together, which meant reconciling the irreconcilable. Many see this as compromise, not realising that he achieved what you need from a leader – team work.”

Nehru, he said, also supported his subordinates, “holding them up when they faltered rather than punishing or dumping them. He would point to their strengths and suggest how their talents could be better used elsewhere.”

He would concede where a movement was democratic and widespread as in the demand for Nagaland, but he refused the much more intense and prolonged Akali demand for a Punjabi Suba on the ground that it was communal, not linguistic. He did not waver on the strategic objectives of unity, independence, citizenship, democracy, and growth; compromising on lesser objectives furthered these fundamental ones.”

So why does India’s first PM raise hackles of the Sangh Parivar, his staunch ideological rivals till date? “Because his nationalism was inclusive – that is, all those resident in India were included; other nationalisms in India are exclusive, be it Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, the linguistic, the regional, and so on. Second, he was genuinely global, not insular. He was obviously proud of being Indian, but like Gandhi and Tagore, he considered it absurd to exclude what the rest of the world had to offer.

“It seemed to him a form of self-mutilation to do so. People who are parochial and exclusive, afraid of the wide open world, detest him.”

Are there any fresh details on what Nehru was planning to do with Sheikh Abdullah in Kashmir a few months before his death in 1964? Palat said, “Unfortunately not. Kashmir is a closely guarded secret by all governments, and we have little or no archives on it.”

It is hoped that the hundred books will be online soon, as there is immense interest in international Libraries. More so, as these are almost the Collected works as very little material has been kept out.

So was the last item that Nehru had penned the night before he died a poem by Robert Frost.

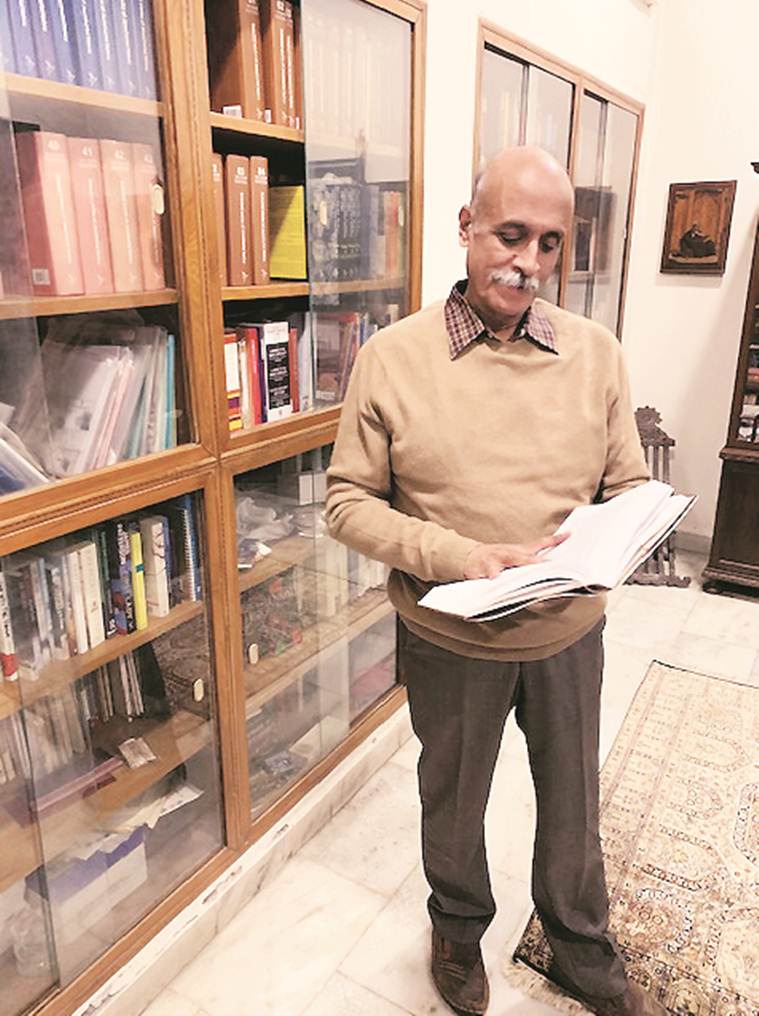

No, said Palat, leafing through the 100th book, “it is a letter to a devout Buddhist and peace activist, Siiche Hirose from Japan, written on May 26, 1964, thanking him for “the three images of Lord Buddha presented to India, which we regard as a very valuable gift and as a symbol of goodwill and friendliness between our two countries.”

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05