- India

- International

Taking stock of infant deaths: in Rajasthan, Gujarat and the rest of India

As outrage continues over the deaths of babies in J K Lon Hospital in Kota, Rajasthan, and in the civil hospital in Rajkot, Gujarat, the fact remains that India has the most child deaths in the world. In 2017, UNICEF estimated 8,02,000 babies had died in India.

Sick children with their mothers at J K Lon hospital in Kota, Rajasthan. (PTI Photo/File)

Sick children with their mothers at J K Lon hospital in Kota, Rajasthan. (PTI Photo/File)

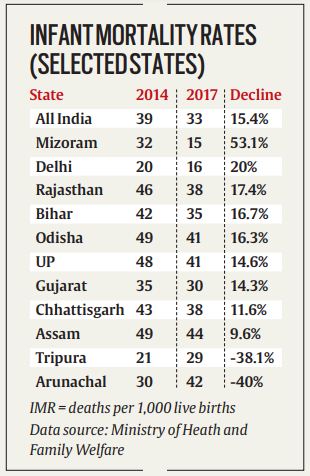

Every day, India witnesses the death of an estimated 2,350 babies aged less than one year. Among them, an average 172 are from Rajasthan and 98 from Gujarat. In 2014, of every 1,000 children born in the country, 39 did not see their first birthday. Today, that figure has come down to 33. That is 1,56,000 fewer deaths every year.

As outrage continues over the deaths of babies in J K Lon Hospital in Kota, Rajasthan, and in the civil hospital in Rajkot, Gujarat, the fact remains that India has the most child deaths in the world. In 2017, UNICEF estimated 8,02,000 babies had died in India.

How high are the mortality numbers?

India has an annual birth cohort of approximately 26 million. The infant mortality rate (IMR) in the country currently stands at 33 per 1,000 live births. This means babies numbering in the region of 8,50,000 die every year in India, or an average daily toll to 2,350. Gujarat has an annual birth cohort of 1.2 million. In 2017, the infant mortality rate in the state was 30 per 1,000 live births. This means the state sees about 36,000 deaths a year, or an average 98 a day.

In Rajasthan, an estimated 1.65 million births take place every year. The infant mortality rate is 38 per 1000 live births which implies an estimated 62,843 deaths annually, or an average 172 every day.

(Source: Ministry of Heath and Family Welfare)

(Source: Ministry of Heath and Family Welfare)Do Gujarat and Rajasthan have the highest infant mortality?

No. Between 2014 and 2017, India’s IMR has declined by 15.4%. At a decline rate of 17.4%, Rajasthan has been ahead of the national average in reducing IMR while Gujarat has a decline rate of 14.3%. The IMR in Rajasthan dropped from 46 per 1,000 live births in 2014 to 38, and in Gujarat from 35 to 30. In 2017, states such as Arunachal Pradesh (42), Madhya Pradesh (47), Assam (44), Uttar Pradesh (41), Meghalaya (39), Odisha (41) and Chhattisgarh (38) had a higher IMR than Gujarat and Rajasthan. Arunachal, Tripura and Manipur have recorded a negative reduction rate between 2014 and 2017, which means child death rates there have gone up. In Arunachal it went up from 30 to 42, in Tripura from 21 to 29 and in Manipur from 11 to 12.

Why do so many infants die in India every year?

On January 1, 2020, according to a UNICEF estimate, India, with an estimated 67,385 babies born that day, accounted for 17% of the estimated 392,078 births globally. This is higher than the 46,299 babies born in China that day, the 26,039 born in Nigeria and 16,787 born in Pakistan.

Among the factors that have been proved detrimental to child survival are lack of education in the mother, malnutrition (more than half of Indian women are anaemic), age of the mother at the time of birth, spacing, and whether the child is born at home or in a facility. According to a UNICEF factsheet on child mortality in India, “… Children born to mothers with at least 8 years of schooling have 32% lesser chances of dying in neonatal period and 52% lesser chances in the post-neonatal period, as compared to the illiterate mothers.” It also notes that infant and under-five mortality rates are highest among mothers under age 20. The rates are lowest among children born to mothers between the ages of 20-24, remain low up to 25-34, and increase again after that age.

According to the National Family Health Survey-4, only 78.9% births in India happen in a facility. This means 21.1% or about 54 lakh births in a year still happen outside of a facility where hygiene levels can be low, sometimes without the help of a trained health worker. Apart from the obvious infection risks in a non-institutional birth, vaccine compliance too is usually worse in these cases. According to the Health Ministry, the vaccination cover in India after several rounds of Intensified Mission Indradhanush (MI) and the original MI, now stands at 87%. This means over 33 lakh children continue to miss out on some or all vaccinations every year.

What measures are in place for sick newborns?

Special newborn care units (SNCUs) have been established at district hospitals and sub-district hospitals with an annual delivery load more than 3,000 to provide care for sick newborns: that is, all type of neonatal care except assisted ventilation and major surgeries. It is a separate unit in close proximity to the labour room with 12 or more beds, and managed by adequately trained doctors, staff nurses and support staff to provide 24×7 services.

According to officials in the Health Ministry, approximately 1 million children are admitted to the 996 SNCUs in the country every year with an average death rate of 10%. “The death rates are usually higher in medical college-based SNCUs like J K Lon (Kota) because they tend to get sicker babies, sometimes from faraway districts when parents rush them there in a last minute effort. J K Lon (Kota) for example has a 20% death rate. But that is because the challenges are higher,” said a senior Health Ministry official dealing with child health.

In AIIMS, New Delhi, usually only those newborns are admitted who are born there and these usually come from high-risk pregnancies. “The mortality rate for intramural cases is about 1.5% but these are low birth weight babies, pneumonia, sepsis. Extramural cases we only take those that are very sick, babies that nobody else will take such a heart disease kidney failure etc. Overall 10% has been the mortality figure since the time SNCUs began to be monitored nationally,” says Dr Vinod K Paul, member NITI Aayog and former professor of paediatrics at AIIMS.

Don’t miss from Explained: The nominal GDP worry

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 19: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05