- India

- International

Streetwise Kolkata: Strand Road, along the edges of River Hooghly, was built with public lottery funds

Although it is not known when Strand Road was completed, its development not only served to demarcate the city’s western boundary, but it also helped in the development of the strategically important Port of Calcutta that required cleared waterways and embankments.

An old building along Strand Road in Kolkata. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

An old building along Strand Road in Kolkata. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

On the right bank of the Hooghly river in Kolkata, one of the city’s longest thoroughfares, Strand Road runs parallel in a long stretch in the business district in the centre of the city. The neighbourhood has a unique collection of some of the city’s most diverse and astonishing architectural heritage, although much of it has dilapidated due to neglect over the years.

Metcalfe Hall, a heritage building, stands at the junction of Kolkata’s Strand Road and Hare Street. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

Metcalfe Hall, a heritage building, stands at the junction of Kolkata’s Strand Road and Hare Street. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

When Richard Wellesley was appointed Governor-General of India in 1789, he initiated the ‘Minute of 1803’, a street policy that was aimed at the “native inhabitants” and the seemingly improper way their houses had been built “without order or regularity” and the streets and lanes “formed without attention to the health, convenience or safety of the inhabitants”, writes S W Goode, in his book ‘Municipal Calcutta: Its Institutions in Their Origin and Growth’ published by the Corporation of Calcutta in 1916. The British government in India believed that it was their “primary duty” to establish a “comprehensive system” for the development and improvement of the city’s streets and roads and to lay down permanent rules for the construction of homes and public spaces.

Read | Streetwise Kolkata: How Tollygunge is linked to Tipu Sultan

The policy was implemented by the institution of the Town Improvement Committee that was responsible for constituting a complete street scheme for the city of Calcutta. The ambitious scheme, although sanctioned, funded and implemented by the British government, could only be partially executed because of a shortage of funds. The Lottery Committee was hence set up in 1817, to collect funds for the city’s development through public lotteries.

The funds disbursed through the Lottery Committee saw the development of the long stretch of Strand Road, from north to south, right from Hathkhola to Prinsep Ghat with shorter streets and bylanes running in between, like Elliot Road, Wood Street, Wellesley Street, Wellington Street, College Street, Cornwallis Street, Hastings Street, Moira Street, Loudon Street, Amherst Street and Hare Street. The funds also helped in the widening and straightening of Free School Street, Kyd Street, Mangoe Lane and Bentinck Street, all in central Calcutta.

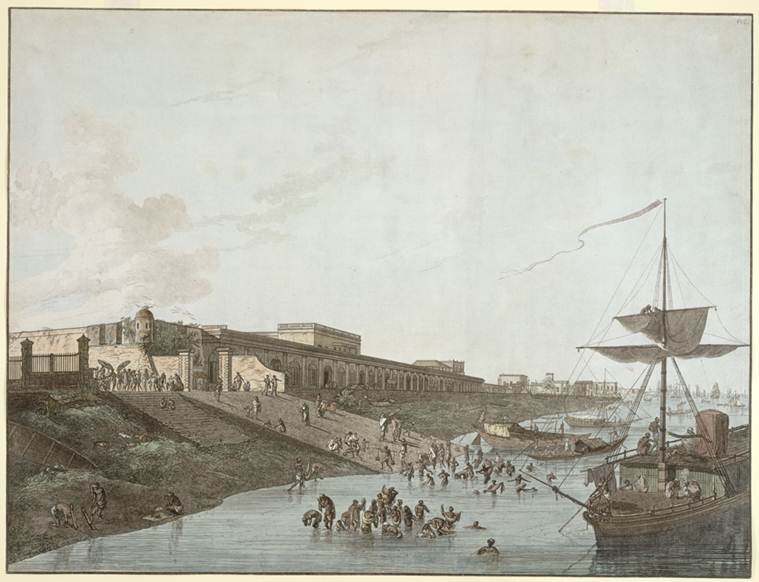

This is a coloured etching of the Old Fort Ghat adjoining old Fort William in Calcutta by Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) and is part of his collection titled ‘Views of Calcutta’ published in 1787. The British Library says for this etching: “The old Fort was built at the turn of the eighteenth century. In 1757, an attack on the fort by the forces of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, led the British to build a new fort in the Maidan. The old Fort buildings were repaired and used as a Customs House from 1766. Both goods and passengers were unloaded from ships at the landing-stage shown here. The ghat was also a popular bathing place for the people of Calcutta.” (Photo: The British Library)

This is a coloured etching of the Old Fort Ghat adjoining old Fort William in Calcutta by Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) and is part of his collection titled ‘Views of Calcutta’ published in 1787. The British Library says for this etching: “The old Fort was built at the turn of the eighteenth century. In 1757, an attack on the fort by the forces of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, led the British to build a new fort in the Maidan. The old Fort buildings were repaired and used as a Customs House from 1766. Both goods and passengers were unloaded from ships at the landing-stage shown here. The ghat was also a popular bathing place for the people of Calcutta.” (Photo: The British Library)

The road, so named because it was built on the edges of the river, was developed to form a western boundary for the city of Calcutta. In 1820, the Lottery Committee considered the development of “a wharf and a road to the north of the Old Fort Ghat’, adjoining the premises of what is now Fort William. “Even at that early date, difficult questions of title to the alluvial lands along the Hughli had arisen,” writes Goode. “The Committee was of the opinion that (the British) Government had an incontestable right to all alluvial lands not included in the pottas of the riverside proprietors.” According to the Calcutta Review Vol. VI, published in 1846, ‘pottas’ is a term for undeveloped land leased to tenants who have no fixed rights and hold the land at the will of a government authority.

Read | Streetwise Kolkata: Chowringhee is older than the city of Calcutta

Records from 1820, states Goode, show that “some of the potta holders demanded compensation that was paid to them, while others freely surrendered their lands to the East India Company for the purpose of the road, reserving however to themselves their right to the land west of the road down to the water’s edge.”

Traditional boats docked at Babu Ghat in Kolkata. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

Traditional boats docked at Babu Ghat in Kolkata. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

There are varying accounts of when the construction of Strand Road began and ended. H E A Cotton, in his book ‘Calcutta, Old and New”, writes that the Strand Road was completed in 1828 and made its way down to the neighbourhood of Hastings and near Prinsep’s Ghat, a structure that was completed two decades after the construction of the road. Goode, however, writes that work concerning Strand Road started only in 1828, having been financed by public subscriptions, “raised in the form of shares, which were repaid with interest from a toll levied on passengers and vehicles at the bridge across the mouth of Tolly’s Nullah.” The cost of constructing Strand Road that year came to Rs 1.5 lakh, Goode writes, but the Municipal Office did not appear to have documentation concerning when the construction was completed and nor what it ultimately cost after completion. “No other of the fine public works which Calcutta owes to the Lottery Committee compares in its far-reaching importance to the Strand Road,” says Goode.

A photograph of the Strand from Samuel Bourne’s collection, ‘Views of Calcutta and Barrackpore’ taken in the 1860s. The British Library says for this photograph: “The Strand extends along the Calcutta’s Hooghly river from the northern point of Chandpaul Ghaut to beyond Fort William and Prinsep’s Ghaut, near Tolly’s Nulla. The Road was part of Marquess Wellesley’s scheme for the embankment of the river.” (Photo: The British Library)

A photograph of the Strand from Samuel Bourne’s collection, ‘Views of Calcutta and Barrackpore’ taken in the 1860s. The British Library says for this photograph: “The Strand extends along the Calcutta’s Hooghly river from the northern point of Chandpaul Ghaut to beyond Fort William and Prinsep’s Ghaut, near Tolly’s Nulla. The Road was part of Marquess Wellesley’s scheme for the embankment of the river.” (Photo: The British Library)

Although it is not known when Strand Road was completed, its development not only served to demarcate the city’s western boundary, but it also helped in the development of the strategically important Port of Calcutta that required cleared waterways and embankments. Goode writes that had the potta settlements on the banks of the river been allowed to settle and become more permanent in nature over the decades, the government would have had a difficult time clearing them away to construct the port in 1870.

Cotton writes that the Lottery Committee looked after the affairs of the city of Calcutta till 1836 and among the streets and lanes the Committee had been instrumental in setting up, it was also responsible for constructing roads and paths that run across the Maidan area and the low balustrades that exist even today, running on the side of the roads around the Maidan. Along the stretch of Strand Road, the Committee also established the Babu Ghat on the riverside and the Respodentia Walk towards the south, “which has long since disappeared but would be used for moonlight walks.”

The Lottery Committee also established Babu Ghat on the banks of the Hooghly river in the Strand Road neighbourhood. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

The Lottery Committee also established Babu Ghat on the banks of the Hooghly river in the Strand Road neighbourhood. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

It is impossible to write about Strand Road without mentioning the Strand Bank because the two are so closely associated with each other. The Strand Bank, a stretch of road just beyond Strand Road to the north, was a result of alluvial deposits of the Hooghly river and the Military Board in Bengal attempted to protect the riverside, especially at Fort William, from erosion by building spurs, also called artificial embankments. This neighbourhood consisted of valuable land, and the British government began dumping refuse that had collected as a result of “town sweepings” to create reclaimed land on the banks of the river.

In 1848, Goode writes that the “town sweepings” began to create a nuisance, presumably due to the sight of dirty refuse and its stench, and the municipality office stepped in to permanently cover it up. The increase in the property value of the neighbourhood and the subsequent income led to the creation of the Strand Bank Fund, which was in turn used to drain parts of the Maidan to plant their own trees and plan the open space. These funds were also used by the British government to “embellish” and develop the Eden Gardens and the Esplanade nearby.

The profitability of the land around Strand Road meant that people living around it wanted a share that was being pocketed by the British government, and that included the “pottadars”. The British government however, claimed that the “pottadars” had given up their claims on the land in 1820 itself, agreeing only to use of what would now be public property, on condition that there would be no elevated buildings and only government buildings for public welfare. James Broun-Ramsay, the 1st Marquess of Dalhousie, who became the Governor-General in 1848, said that although the “pottadars” in 1820 had been made to believe that their location on the banks of the river would give them advantageous use of the road and the river frontage, the government had plans to further develop the banks of the river into public spaces like ghats and wharves but had no plans for elevated buildings, partially adhering to the promises made by the British to the “pottadars”.

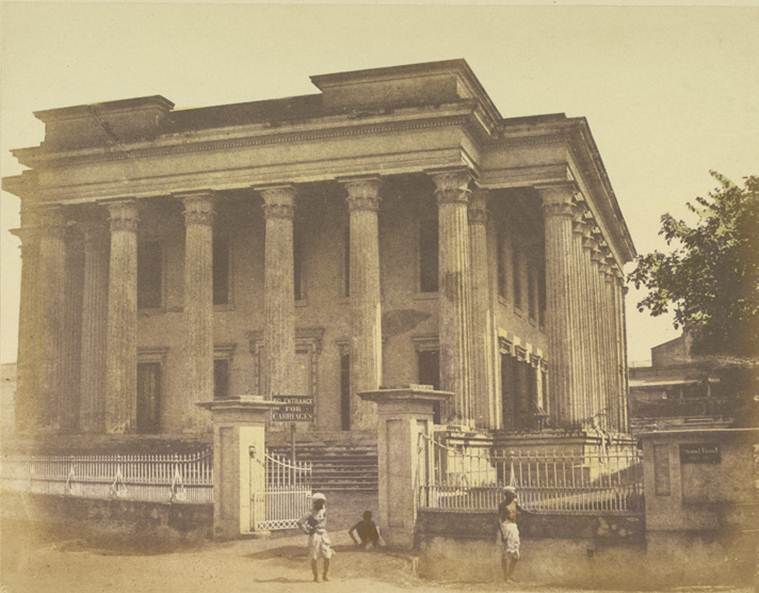

This hand-coloured print of Metcalfe’s Hall, Calcutta, belongs to the Fiebig Collection, ‘Views of Calcutta and Surrounding Districts’, taken by Frederick Fiebig in 1851. According to the British Library, “this is a view from Strand Road of Metcalfe Hall, which at one time was home to the Imperial Library. The Hall to commemorate Lord Metcalfe was designed after the Temple of the Winds in Athens, and built in 1844.” (Photo: The British Library)

This hand-coloured print of Metcalfe’s Hall, Calcutta, belongs to the Fiebig Collection, ‘Views of Calcutta and Surrounding Districts’, taken by Frederick Fiebig in 1851. According to the British Library, “this is a view from Strand Road of Metcalfe Hall, which at one time was home to the Imperial Library. The Hall to commemorate Lord Metcalfe was designed after the Temple of the Winds in Athens, and built in 1844.” (Photo: The British Library)

One advertisement in the Calcutta Gazette of 1828 indicates that in that year, Strand Road was open for pedestrians and traffic without tolls, indicating that almost all work on the road had been completed by then. After evicting the “pottadars” from their land, the British reneged on their promises and engaged in rampant construction of elevated government buildings around the neighbourhood, on some of the most expensive real estate in the city, including the Shipping Corporation of India, the Metcalfe Hall and the High Court of Calcutta. The neighbourhood also included boarding and residence for sailors who were involved in maritime trade and shipping in the city.

According to the British Library, this photograph of the Sailor’s Home from the ‘Walter Hawkins Nightingale (PWD) collection: Album of views of Calcutta’, was taken by an unknown photographer in the late 1870s. “The Sailor’s Home in Calcutta was situated on the Strand Road and overlooked the River Hooghly just north of the junction of Strand Road with Hare Street. In the late 18th century the Sailor’s Home was pulled down and replaced with the Magistrate’s Court.” (Photo: The British Library)

According to the British Library, this photograph of the Sailor’s Home from the ‘Walter Hawkins Nightingale (PWD) collection: Album of views of Calcutta’, was taken by an unknown photographer in the late 1870s. “The Sailor’s Home in Calcutta was situated on the Strand Road and overlooked the River Hooghly just north of the junction of Strand Road with Hare Street. In the late 18th century the Sailor’s Home was pulled down and replaced with the Magistrate’s Court.” (Photo: The British Library)

Today, if one were to walk down the entire approximately five-kilometre stretch of Strand Road, from Hathkhola all the way down south to Prinsep Ghat, it would make for an incredibly chaotic visit. The pavements running along the side of the ride are blocked by hawkers selling everything from metal keys and locks to fruits and tea, with little space for pedestrians. The red-brick warehouses along the riverside that were instrumental to maritime trade over the centuries lie mostly in disrepair, sections of which have been occupied by squatters.

Upon exiting the business district in B.B.D. Bagh, and moving down south to Chandpal Ghat, towards the left of the riverbank looms the New Secretariat Building, constructed by noted architect Habib Rahman in the Bauhaus style in the early 1950s. The building, despite its storied creator, seems to stand out like a sore thumb among the grand colonial structures that surround it. Just further down is the large expanse of Eden Gardens, a view of the Maidan beyond and the sprawling army quarters of Fort William. A little further down, if one continues walking on the banks of the river, towards the neighbourhood of Hastings, comes an unparalleled view of the Vidyasagar Setu, the longest cable-stayed bridge in the country and the long Doric columns of the Prinsep Ghat, established in 1841, frequented by young adults seeking privacy.

The iconic Prinsep Ghat, established in 1841, is easily recognisable due to its long Doric columns with the Vidyasagar Setu in the background. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

The iconic Prinsep Ghat, established in 1841, is easily recognisable due to its long Doric columns with the Vidyasagar Setu in the background. (Express Photo: Shashi Ghosh)

No documentation or trace remains of what happened to the “pottadars” who were cheated and evicted by the British to give the city some of its most expensive and important real estate. The traffic flow of cars, rickshaws and pedestrians on this road temporarily subsides as dusk falls on the city, but it never entirely abates, rendering the neighbourhood in a state of perpetual motion. Beneath the grime, chaos and crumbling heritage in this part of the city, the history and grandeur of the Strand Road can still be found for those who are willing to search for it.

Must Read

Apr 23: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05