After 50 years of writing more than 50 plays, David Williamson insists he is retiring from the theatre.

Turning 78 this February, the Noosa, south Queensland-based playwright is about to see his last two new plays produced back to back in Sydney where he built his career, while his classic semi-autobiographical satire of the harbour metropolis, Emerald City, will be remounted in a new production in Brisbane and Melbourne.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the fact he is widely regarded as Australia’s most commercially successful playwright, with a loyal audience hooked on his naturalistic style of storytelling about the white middle class, Williamson’s relationship with the people he sees as the cultural gatekeepers – theatre critics – has been fraught. Williamson says critics dismiss his work because it is popular, although the quality of his work has also been questioned. He once accused the Sydney Theatre Company of ignoring his plays “because I’m not theatre with a capital T”.

Williamson argues his playwrighting has always examined human psychology and verbal self-deception. But he now says he wants to make way for younger voices, including the minority playwrights he acknowledges have been denied a platform, to tackle the many issues Australia is facing. He’s had a “dream run”, he emphasises, and “can’t whinge” about his unabated box office success.

For Williamson, who has five children and 14 grandchildren, retirement is also motivated by his health: he has a long-term heart rhythm problem and several years ago suffered a transient ischaemic attack, which temporarily paralysed the right side of his body. “The whole process is stressful, from the writing of 12 or 15 drafts to the whole business of opening nights,” he says. “For many years, I couldn’t even go to an opening night. I had to have Kristin [Williamson, his wife and a fellow writer] reporting to me how things were going.

“You go to a brilliant opening night, you know it has connected, and then you think [of the critics]: ‘Oh those fuckers’. I remember one [review] line that said, ‘I sat with a dark cloud hovering above me as people fell off their seats laughing around me’. And you think, what is so terrible about that? Why did the black cloud descend upon him to see people enjoying themselves in the theatre?”

Famously, Williamson’s writing has often been clearly drawn from his experiences. In the early 1970s, he left his then-pregnant wife for his current wife, who also left her husband. This became the basis for his early play Jugglers Three, a depiction of two marriages breaking up, rewritten many years later as Third World Blues in which a character called Elizabeth accuses a character called Neville, based on Williamson, of having a “hyperinflated ego”.

Is everything in his life playwriting material? “Well, I have drawn on life. Any writer who says they don’t is lying. But you do change and alter [the details].”

In her 2009 biography of Williamson, Kristin – who met the playwright when she was cast in one of his early plays – argued that the “outraged letters and emails” her husband “fired off in fits of rage” to critics, directors and producers were borne of a sensitivity that also made him an “astute dramatist” who could perceive “malignant undercurrents in social behaviour”.

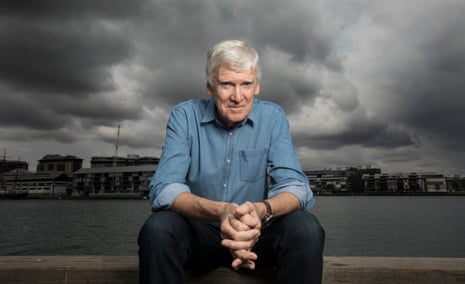

We meet in the rehearsal room for his new play Family Values. Williamson stands more than two metres tall; he used to fantasise about being shorter so he wouldn’t stand out so much. He is affable, sincere, a good listener, eloquent and forthcoming in his responses, although he brings up the critics of his work much earlier than I had planned: it’s clearly a spectre that will always bother him, even while acknowledging he has overreacted on occasion.

He agrees with his wife’s take on his psychology – but adds the rhythms of the “bitter fighting” between his late parents, gregarious retail saleswoman mother Elvie and quiet accountant father Keith, also “enormously” influenced his work.

“I didn’t realise it at the time, but my brother and I grew up in a house of perpetual drama,” he says. “There was hardly a minute when they weren’t having a go at each other. It wasn’t until the age of 11 that I realised it was a bit more complex than that, when I caught my mother goading my father to the point of an explosion.

“He was never a physically violent man, but finally he could be provoked into calling her names. I remember when my mother raced out to the laundry, and I followed her: she was chuckling away.” A few years before her death, Williamson brought up the memory, and asked her what was going on. “Well, it did get pretty boring in the country,” she answered.

“She was sparking the drama,” he says now. “I spent my young life wondering, ‘How can I avoid this? Is this what marriage means?’”

Born in 1942, Williamson grew up in the middle-class suburb of Bentleigh, then on Melbourne’s outskirts. The family moved when he was 12 to country Bairnsdale.

At the time, theatres in Australia offered virtually no plays about contemporary Australian society. In 1964, Williamson became Monash University’s first graduate in mechanical engineering – but as an assistant project engineer at General Motors-Holden he would read Chekhov under the desk.

Williamson’s subsequent study of psychology at Melbourne University would inspire him to think of himself as a “social scientist”, and he began writing plays. In 1971, his middle-class suburban election night satire, Don’s Party, was a hit at the Pram Factory, but the collective that ran La Mama theatre in Carlton thought it too bourgeoisie – so he wrote them a hard-hitting look at police and male brutality, The Removalists, which won him a prestigious award in London.

Instead of moving his career there in the wake of this international attention, he sensed his continued connection to Australian place and vernacular was critical to his writing. Williamson stayed home and rode the 1970s Australian “new wave” film industry resurgence, adapting many of his stage plays into successfully produced screenplays.

In his youth, Kristin Williamson wrote, David “became a zealous leftwinger, to the extent that he tried to convert his parents”. Is he still politically to the left? “Oh yes,” he says now. “Despite what some of my critics have said about me being a social conservative, there is an underlying social concern in all but a few of my plays. I always hope to be entertaining on the surface, but saying something about the state of our society in the subtext.

“I haven’t lost that. I am so angered by the growing injustices and inequalities in the world that it does still fire me up. It’s almost painful to pick up the Murdoch press every day and see the blatant attack on social progressivism of any kind, the fervent belief in neoliberalism, despite the world heading towards a real catastrophe.

“The honchos tend to be ageing white males, wealthy white males, who are incredibly threatened by the science of climate change, because it threatens their whole world view that neoliberalism has delivered huge prosperity to the world, that growth can go on forever, that there will be no evil consequences.”

Indeed, Williamson’s final two new plays offer social critiques of Australia now. Family Values reflects the writer’s disdain for Australia’s refugee policy, and has an asylum seeker character. Mandatory offshore detention “has been one of the morally despicable acts the Australian government has carried out, and both sides are guilty – Labor started it”, he says. “I fail to understand Jacqui Lambie voting against medevac because she said openly medevac is no threat to Australian security.”

The other play, Crunch Time – a blackly comic story of a father and son healing a relationship – carries the theme of assisted death. Williamson laments the failure of most states to adopt voluntary euthanasia laws. “The NSW Liberal party seems to be still in thrall of the religious right, and it’s the lizard brain dictating the rational capacity of human beings; it’s some emotional fear that someone is going to turn the switch off on them, or God wants to prolong our pain as long as possible before we have a decent death,” he says.

Would Williamson want voluntary euthanasia for himself, if it came to that? “Absolutely. I saw a friend die recently of pancreatic cancer, and they fade away to a human skeleton. It’s a horrible way to leave an image for your loved ones.

“I’d rather go out when they still recognise me as me, so there’s a bit of vanity, but also I’d want to avoid the extreme pain of the end game.”

Family Values runs at SBW Stables at Griffin Theatre in Sydney from 17 January until 7 March. Crunch Time runs at Ensemble Theatre in Sydney from 14 February until 9 April. Emerald City runs in Brisbane at QPAC Playhouse from 8-29 February, and in Melbourne at Southbank Theatre, The Sumner from 6 March to 18 April.