- India

- International

The University That Built Me

At Jawaharlal Nehru University, I learned to shed my many layers of privilege and realised that there is nothing apolitical about life.

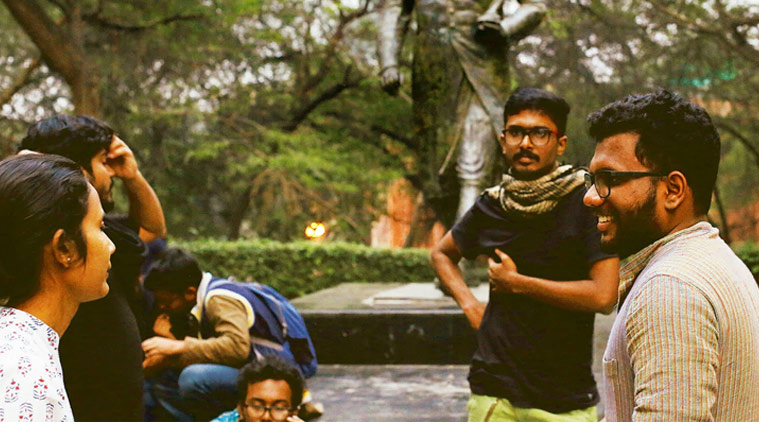

Seat of learning JNU enters one’s bloodstream, slowly but surely, reconfiguring the person. (Photos: Express Archive)

Seat of learning JNU enters one’s bloodstream, slowly but surely, reconfiguring the person. (Photos: Express Archive)

When I first came to JNU, joining the School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies for an MA in English literature, I affected a studied insouciance about the political scene on campus. August was about to end, the year was 2005, and while American troops were rampaging about Iraq and Afghanistan, bougainvillea flowers had painted our campus in streaks of magenta and white. When rainclouds massed in the sky, in the somnolent forests by the southern stretch of the Ring Road, you sometimes caught a glimpse of the iridescent colours in a peacock’s train as it twerked to impress its mate. It was all very atmospheric. Even though there was a long waiting list for a hostel room and I was sleeping on the floor in a friend’s room as a guest, I had begun to feel so solidly at home in the university that I suspect my parents in Calcutta felt a bit betrayed by their only child.

“I am done with politics,” I told anyone who made overtures at me. Recruiting members of the new flock to one’s ideology was something that absorbed most politically-minded students on campus in the monsoon semester, across party lines, and these conversations could happen anywhere — in the bathroom while we filled our buckets in the morning as water would run out after 9 am, in the department canteen after classes on African literature, or late at night in Ganga Dhaba, over anda parathas and too-sweet tea. “Honestly, I am done,” I emphasised, managing to sound as jaded as is possible when you are 21 years old.

I had done my share of politics at Presidency College, thank you very much. After all, our Independents’ Consolidation had fought and lost a bloodied election on campus, and then, the year after, fought and won a bloodied election (where the victorious Constituency Representatives had to be huddled away in a guesthouse for two days so the ruling party, the Students’ Federation of India, couldn’t get to them before election day) and while I had enjoyed the drama intensely at the time, that life was now behind me, in Calcutta. I was looking forward to changing the world through literary theory. Or rasa theory, I corrected myself in a self-conscious post-colonial swipe.It was somewhat of an obfuscation though.

The truth was that I had come to JNU for two reasons, and literary theory was not one of them, not really. The first reason was love. My boyfriend, whom I later married, was a student in the economics department at School of Social Sciences, and a heady idealist. We had fallen in love back in college (we had both contested in the historic Presidency elections) and since he was senior to me, he had come to JNU a year ago. Apparently, in addition to politics, I was also done with long-distance relationships. The second reason was infinitely more complicated. I wanted to be a writer. Though I had never allowed the words to come together and coalesce in my head in that order, of course not. (It was 2005, and from where we came, young people didn’t go around saying things like “I want to be a writer” because that meant you wanted to be published, an objective-oriented bourgeoisie position, and so, at best, you said, “I want to write”). But it was true, and I knew it in my bones. And somehow, despite never having thought of writing in terms of process or craft, I knew even then that my future, my JNU years, was going to give me my material. Politics was only one part of the larger JNU story, of course, and I wanted all of the story.

Just to remind you, I was 21. And so, my eyes slightly wide and my palate strangely keen, I listened to people’s stories, and through these small individual narratives, JNU entered my bloodstream and, slowly but surely, reconfigured me. One of the most interesting sources for me was Saurav’s roommate, V, a student of Russian now in his MA. V was a Bhumihar from Bihar. (You were given that fact at hello.) While V was loosely connected to the ABVP — in the Vajpayee years, ABVP had grown on the campus — he had close links with a very large number of Bhumihars on campus who cut across party lines. At the time, people were still able to maintain friendships across party lines, a proposition now becoming increasingly fraught. His friends often lounged about in their room, while I puttered away on Saurav’s desktop and heard their tall stories. It was a far cry from my own classmates and seniors who peppered their conversation with “deconstruction” and “hetero-normativity” and “interpellation” and “the nation and its fragments”.

And so it was here, in this dingy room in Jhelum Hostel, that I came to meet a senior from School of International Studies who had just submitted his PhD thesis on West Asia. B, though everyone called him Bhaiya, was in his late-20s, given to laughing loudly, and I remember that, at the time, he had seemed almost impossibly old to me. Someone brought tea, I had biscuits in my bag, it all got pleasantly boisterous. Bhaiya remarked that he was preparing for the UPSC one last time and was working for a Hindi magazine on the side. “Wouldn’t it be better if you quit your job and focussed entirely on UPSC?” I asked him.

It was an earnest question. I can see myself now, looking sideways at Bhaiya, away from the computer screen where my essay on Toni Morrison still incomplete, in my cotton kurta and jeans, as comfortable in my skin as in my many layers of privilege. Bhaiya smiled.

Like many of the well-read Biharis and UP-wallahs on campus, Bhaiya had the talent of not offering a straight answer while offering a straight answer. He said, “You know, in all the years I have been a student here, every time I come to Delhi from home, my father says, ‘Shall I send some rice? Vegetables? At least take a few kilos of atta with you?’” He spoke softly, and I had to strain my ears to listen. The others had all fallen quiet. “He has never been able to say, ‘Here, take some money. You’ll need it for the journey, to pay for your studies.’ It was always the talk of the rice and the vegetable and the atta. And every time I would laugh and say, ‘Don’t worry pitaji, they feed us well in the hostels.”

My face flushed, and the words dried up on my tongue. At the time, our mess fees were around Rs 800 a month. Mess and hostel dues and registration fees for a semester were nominal enough for the likes of my parents, even though my pocket money was always limited, but for Bhaiya’s father, a farmer, even this was unaffordable. (The fee hike which the students of JNU are protesting today, incidentally, is a hike from Rs 3,000+ per month — only hostel fees, mind you, not the other costs that students have to bear, books and photocopies and other things — to Rs 6,000+ per month).

If I learnt anything from that conversation, it was to become a little more self-aware, a little less wrapped up in my own self-importance. I didn’t understand it then but, later, over the years, when grief and joy had both broken me down and re-purposed me again, this story would return to me, once, twice, and then again and again, not just what Bhaiya said and what it meant but all of it, my context, his context, the dingy room, the sunlight fading outside, the laundry drying on lines, the boys laughing in the courtyard, the books and the papers that were piled in every room in that hostel, in all the hostels of that campus, the sofas in the homes of the professors where we sometimes hung out and ate, the workers outside who, invisible to the career-minded students, re-paved roads and re-painted walls and repaired toilets and then re-did them again the next day. The small-ness of it all, the large-ness of it all, the wonder of it all. I stopped going around saying ridiculous things.

I was far from done. We are all far from done.

Devapriya Roy is a Delhi-based writer. Her newest book is Friends from College.

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05