- India

- International

Pakistani Hindus living in Jodhpur camps believe Citizenship Act is their passport to future

In 2016, Jodhpur was among the 16 districts in the country whose collectors were empowered by the Centre to grant Indian citizenship to legal migrants from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian communities (the same group that CAA covers as well).

Residents of Anganva Basti prepare for dinner as the day comes to an end. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

Residents of Anganva Basti prepare for dinner as the day comes to an end. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

“Aa jayenge woh bhi… inshallah (They will come too, inshallah),” says Tara Chand Bhil, 40, referring to his brother and his family who live in Sindh province of Pakistan. A moment later, realising what he just said, he smiles awkwardly.

“Bhaijaan is still not used to the language here. We said inshallah so often in Pakistan,” says younger brother Dilip, himself using a term for brother unusual for these parts.

It was only two months ago that Tara Chand and Dilip along with seven other family members arrived from Pakistan, to Anganva Basti in Jodhpur district. The brothers don’t want to reveal where they lived in Pakistan, scared for their relatives there; most residents here are from Mirpur Khas or Sanghar district of Sindh. They crossed the border through Wagah, bringing only their clothes with them.

As a settlement of at least 250 migrant Hindu families from Pakistan, most of them Bhil tribals along with Koli community members, Anganva Basti was well known to them. As was the border district of Jodhpur, which has more than 15 such settlements.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, speeding up the process of citizenship for migrants like them, has sent a wave of cheer through the camp — including residents who came here in 2013, to those who arrived 45 days ago. None is as yet an Indian citizen.

In 2016, Jodhpur was among the 16 districts in the country whose collectors were empowered by the Centre to grant Indian citizenship to legal migrants from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian communities (the same group that CAA covers as well). Union Home Ministry data shows that since then, most citizenships in Rajasthan have been granted in Jodhpur (ahead of Jaipur and Jaisalmer).

Those like Tara Chand and his brother, living in camps in dismal conditions, are now counting on CAA to see them through.

As per Rajasthan Additional Chief Secretary, Home, Rajeeva Swarup, 17,574 non-Muslims and 331 Muslims from Pakistan are staying in the state on Long Term Visas (LTVs) currently.

Chasing papers

Spread over four-odd acres, Anganva Basti is an arid expanse of row upon row of kuchcha shanties, broken by a few pucca huts. The tarpaulins on the roofs provide the only colour.

The adjacent hillock is overrun with the desert’s thorn bushes as well as human excreta. The residents defecate in the open as there is no water connection or sewerage system. By evening, it’s hard to escape the smell. Hours later, with no power supply, it’s difficult to find one’s way around.

The residents here hold either LTVs or pilgrimage visas, that they took to visit mostly Haridwar and never went back. Intelligence agencies and police keep constant watch, and they are required to pay frequent visits to the Foreigners’ Registration Office.

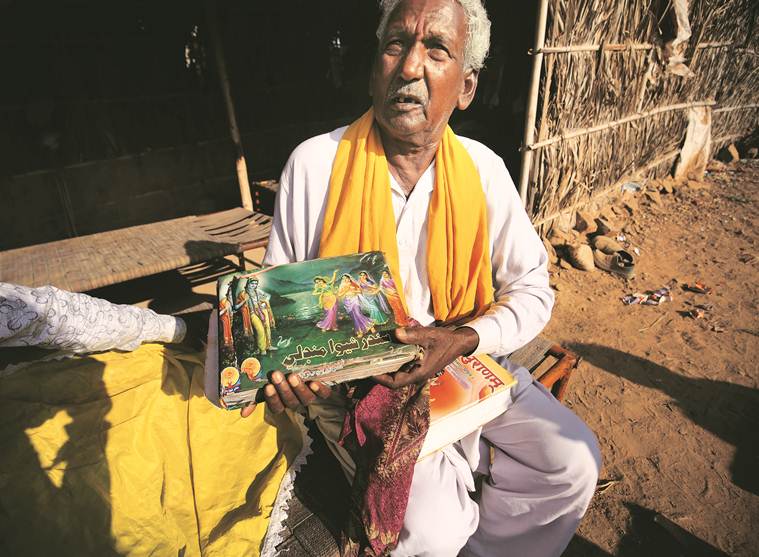

a 70-year-old Hindu migrant shows a copy of the Bhagwad Gita, which is in Sindhi written in Urdu script, one of the few things he brought from Pakistan. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

a 70-year-old Hindu migrant shows a copy of the Bhagwad Gita, which is in Sindhi written in Urdu script, one of the few things he brought from Pakistan. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

On December 20, nearly 50 of them participated in the BJP’s pro-CAA rally in Jaipur.

Sadoro Bheel, 53, is among the earliest residents of Anganva, having migrated in 2013. His makeshift home made of stones is located at the centre of the settlement. He came with his wife and four children (now 16, 12, 12 and 9), with the eldest, 19, who works as a driver, choosing to stay back in Sanghar in Pakistan. Sadoro drives a tractor for a local businessman, transporting agricultural produce, earning Rs 8,000 a month. His wife Shabu works as a daily wager, making Rs 200 on best days.

With no gas connection, Shabu cooks on firewood. Their daughter Ganga, 16, goes to a school run by an NGO, while the other three are in government schools. Back in Pakistan, they didn’t go to school, Sadoro says.

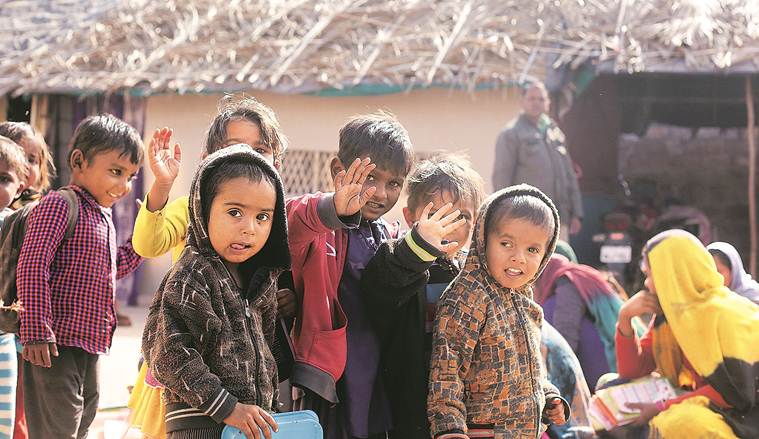

There are approximately 400 children at the camp, of whom around 300 go to government schools. The rest study in classes held by the NGO at the camp. The nearest government school is 1.5 km away; the nearest health centre around 5 km.

With the Thar Link Express between Bhagat Ki Kothi in Jodhpur and Munabao in Barmer, onward to Karachi in Pakistan, discontinued since India-Pak relations deteriorated after the August 2019 scrapping of Jammu and Kashmir special status, travelling to Pakistan has become difficult.

Sadoro and his wife have not been to Sanghar since coming here, and stay in touch with their eldest son on phone.

Admitting he doesn’t know exactly what CAA is, Sadoro says he has heard “it might give us citizenship”. Having migrated in 2013, much before the cut-off date of December 31, 2014, mentioned in the Act, Sadoro and family are entitled to speedy citizenship. But others at Anganva too hope to benefit, with residents claiming they had been told that everyone belonging to the six religions listed would get citizenship in five years.

Sadoro brings out the entire sheaf of papers he lugged from Pakistan in a tin case. He says he left, taking a pilgrimage visa, because he often ended up working and not getting paid. Now, the family is staying on an LTV.

“There’s so much talk, I don’t know what to believe on CAA and what not,” Sadoro adds. “But it would help if I can get a loan to make a house… Our stone home is very cold.”

Chasing promises

Over the years, both BJP and Congress state governments have vowed to take care of Pakistani Hindu migrants. Just before the 2018 Assembly elections, the BJP government relaxed a rule allowing Pakistani Hindu migrants with citizenship to purchase land at concessional rates anywhere in the state. However, again there is little information about this at Anganva, with residents not daring to venture out of Jodhpur, in line with visa restrictions.

The Congress manifesto talked about “holistic development” of Pakistani refugees.

With protests against CAA spreading, Rajasthan Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot has said his Congress government will not implement the Act and that persecuted refugees should be granted citizenship irrespective of religion.

In Rajasthan, the protests, including in Jaipur, Jodhpur, Ajmer and Bikaner, have been largely peaceful. Gehlot and Deputy CM Sachin Pilot were part of one such protest.

Pilot told The Sunday Express, “Anybody who feels they are being persecuted, we will stand in their support. We don’t want to segregate individuals on the basis of religion… Whatever needs to be done from the government’s side will be done.”

Says Rajasthan BJP president Satish Poonia, “On principle, all governments thought of granting these migrants citizenship, but they have been staying as refugees, deprived of facilities such as health, education, government schemes… Given the Rajasthan government’s stand on CAA, there is fear and insecurity among them.”

One of the residents, Jagdish Chouhan, says there is nothing wrong in CAA leaving out Muslim migrants. “Suppose two sides have quarrelled and a third gives one of them refuge. What will happen if both are given asylum? Once again there will be fighting,” reasons the 20-year-old who attended the December 20 BJP rally.

Of approximately 400 children at Anganva Basti, around 300 go to government schools. The nearest is 1.5 km away. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

Of approximately 400 children at Anganva Basti, around 300 go to government schools. The nearest is 1.5 km away. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

Chouhan says increasing harassment of Hindus caused him, his parents and three brothers to leave Mirpur Khas in Sindh in November 2014. They came on pilgrim visa.

More than four years later, they barely make ends meet stitching shirts and trousers for nearby factories, like most others in Anganva Basti, operating out of a one-room shanty.

Lal Chand, who arrived in 2015 with his uncle as a 16-year-old, says they mostly get shirt orders, earning around Rs 13-15 a piece. A science student, he is preparing to take his Class 11 exams through open schooling.

Chand, who too was at the BJP rally, says he misses his parents in Pakistan but is relieved to be in India. Once he has his citizenship, Chand plans to move to Banaskantha in Gujarat, where most of his relatives live since before Partition.

Another resident, who refuses to give his name scared for his relatives back in Pakistan, says he decided to leave after a woman he knew was kidnapped and converted forcibly to Islam.

Mirkhan is among the few residents of Anganwa to have an Aadhaar card. Proudly showing his copy of the Bhagwad Gita, which is in Sindhi written in Urdu script, wrapped in a yellow cloth with Islamic artwork, the 70-year-old says it was among the few things he brought with him. For his Aadhaar card, he had to submit identity proofs of his local guarantor. So, he welcomes the citizenship promise, and is scathing in his criticism of the anti-CAA protests.

“Modiji and Amit Shahji are like god to us for giving us CAA. But look at the protests… If this goes on, India will become Pakistan,” says Mirkhan, as others around him nod.

Asked about what the law would mean for Muslim migrants like Rohingya, Mirkhan says Rohingya are infiltrators and “child molesters”. “We are Hindus who have taken refuge in this country. It’s good our wellbeing is being thought of by the government.”

Word is trickling in about Nita Kanwar, 36, who migrated from Pakistan in 2001, winning panchayat elections from Natwara in Tonk district, five months after being granted citizenship.

Chasing citizenship

A frown creases the sunburnt face of Rewo Bheel, 83, as he talks of the change wrought by Partion in his native Tando Allahyar in Sindh. “First the Sikhs fled, then the Sindhi businessmen. When my family decided to leave for India, our Muslim neighbours said don’t worry… We thought we were landless, didn’t have any property, what is the worse that could happen?” says Rewo.

Sixty years later, in 2005, Rewo migrated with wife Neyan. Son Goverdhan says they faced increasing persecution following the demolition of Babri Masjid in 1992. “Living in Pakistan is like having a house near the sea. It could sink or be washed away at any moment,” Rewa says, sitting outside his one-storey house in Jodhpur’s Radha Beel Basti.

Larger than Anganva, the settlement too has around 250 migrant families, with only 50-odd among them citizens. The walls of most houses are semi-pucca, with saffron flags atop. The residents largely work as labourers or dye clothes at home.

Rewo and Neyan got citizenship in September 2018, after 13 years of being in India. Four months later, his son Goverdhan, 45, and daughter-in-law Radha Bai, who arrived in 2001, also became Indian citizens.

A motley group huddles around Rewa and Neyan as they hold out their laminated certificates carefully, tracing their fingers over the photos and the note in English, which they can’t read, proclaiming them citizens.

Bhurji shows the government identity card issued to him in Pakistan. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

Bhurji shows the government identity card issued to him in Pakistan. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

Precious as it is, the certificate has changed little, says Goverdhan, who runs a homeopathic clinic, while Radha Bai works as a daily wager. Their three children, including eldest Ashok Kumar, 24, a carpenter, are still to become citizens, with no word on an application sent a year ago.

The family has “arranged” for an electric connection in the absence of an official one and purchases water from private tankers for around Rs 2,000 a month. He says their memorandums to MLAs and political leaders have not yielded anything.

Government benefits too remain elusive (Bhils are entitled to Scheduled Tribe status in Rajasthan, and Kolis to Scheduled Caste). “I have been making the rounds for caste certificate, permanent residence proof and ration card. Officials insist on references from relatives for caste certificates. Most of my relatives are in Pakistan!” says Goverdhan.

Prem Bheel, waiting for own citizenship, wonders what Rewo’s family got apart from the right to “go anywhere”. Pointing out that many migrants had families in Jaisalmer and Barmer, Prem says, “There must be some rehabilitation mechanism for us.”

However, the power to travel freely is hardly an insubstantial power, as Goverdhan points out. “If my children too get citizenship, we would go on a trip… to Goa.”

Chasing escape

Six months after her engagement, Kajal, 22, is not sure whether her marriage to Sanjay Kumar will ever happen. Kajal and family live in a rented house in Kudi Bhagtasni area of Jodhpur; Kumar is over 500 km away in Sriganganagar.

“We will take permission for her to live in Sriganganagar. We can’t fix a marriage date before that,” says brother Nawab Chand, who runs a roadside stall of snacks and takes up embroidery work.

Kajal migrated with father Gul Chand, three brothers and their families from Rahimyarkhan in Pakistan’s Punjab province in 2015. In November, she and seven others of the family almost got deported after a Union Home Ministry letter to the state government saying Pakistanis had been found living in Nachna village of Jaisalmer, which is a restricted area for foreign nationals.

The members of the family were said to be involved in “suspicious activities”, including hawala. After the family threatened to commit suicide if deported, the ministry deferred the notice.

Gul Chand, who was among those served the notice, says they had gone to Jaisalmer looking for work and didn’t realise they were breaking a law. “Since the order is only deferred, we live in fear,” says son Kishore Das, who taught in a school in Pakistan and now repairs mobile phones for a living.

On the hawala charge, Gul Chand says, “One of our relatives had sent around Rs 2 lakh after selling some of our property in Pakistan. The money was sent through Oman, where the relative lives.”

Breaking down, Nawab’s wife Parmeshwari says, “Two of my daughters were born in India… Does the government not understand what would happen to us if half our family is sent back to Pakistan?”

The Additional Superintendent of Police, Intelligence, Jodhpur, Kailash Sandhu, says there is status quo in the case. “As per law, foreign nationals cannot go to restricted areas,” he adds.

In August 2017, Chandu Bheel, 80, had been deported from a migrant camp in Jodhpur to Pakistan along with nine other Hindu migrants on the same charge, of flouting visa norms and visiting an area off-limit to foreigners. The Rajasthan High Court ordered a stay, but officials claim that by then, the Thar Express with Chandu and others had already entered Pakistan.

Lal Chand, a tailor by profession, arrived in 2015 with his uncle. Working for a nearby factory, he mostly gets shirt orders, earning around Rs 13-15 a piece. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

Lal Chand, a tailor by profession, arrived in 2015 with his uncle. Working for a nearby factory, he mostly gets shirt orders, earning around Rs 13-15 a piece. (Express Photograph by Praveen Khanna)

Hindu Singh Sodha, president of the Seemant Lok Sangathan, which has been working for the rights of Pakistani Hindu migrants for more than three decades, says, “The Foreigners’ Registration Office, Jodhpur, submitted in the court that we sent back 1,165 Pak migrants in 2014-17. Isn’t it ironic that on one hand there is talk of sheltering persecuted minorities, and on the other, the people who left their belongings to seek refuge in India are being deported?… After return, they face worse harassment.”

Sitting at their two-room house, Kajal speaks little about the delay in her wedding. The house these days is full of friends and relatives who have arrived from Pakistan with plans of settling down in India.

Narrating a family lore passed down generations, 63-year-old Gul Chand says, “My great-grandfather migrated to Pakistan long before Partition. There was heavy drought that year in Jaisalmer where we lived and so he moved to Punjab. He couldn’t return as he didn’t have Rs 5 needed to hire a camel.”

Son Sunder Lal says now the lack of livelihood is killing them in Jodhpur. “We try to find menial work. It is difficult to even pay the house rent of Rs 5,500.”

What keeps them going, he says, is “the hope that one day we will become citizens”. “That is why people here burst firecrackers when CAA was passed”.

Chasing dreams

At 4:30 pm, a long line, mostly comprising women, makes its way towards a temple 400-odd metres from Anganva Basti. They are carrying buckets, plastic containers, tin cans, anything to bring water back from a reservoir at the temple.

With dark falling suddenly in winter, they must return early, navigating the rocky terrain and thorn bushes. Among them is an elderly Jaini Devi. Balancing her buckets, she says it is the last time they can relieve themselves for the day.

Along the way, they cross a few public toilets, choked and useless with waste, bearing the mark of the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan.

Admitting there are issues, Suresh Kumar Ola, the Jodhpur Municipal Corporation Commissioner, says the Anganva camp area falls under the Jodhpur Development Authority (JDA). “It is their responsibility to develop road, sewerage and other facilities… We will check if the residents have any requirements and make them available. We will also write to the JDA.”

Back in a shanty at Anganva, Bhurji, 48, has put concerns behind for now. The family is not done celebrating the birth of his grandson five days ago.

He and six other family members arrived from Kot Ghulam Muhammad in Pakistan in 2017. His grandson will not face “the loot, robbery and harassment faced by Hindus there”, Bhurji says.

Bhurji’s son Motilal proudly shows the baby’s birth registration form. He has decided to name him ‘Deepak’, Motilal beams.

It is on evenings like this that Bhomji, 40, feels the pain most acutely of having left his infant son behind with relatives when he came to India with his wife and five children in 2015. “We tried but couldn’t get a visa for him. How does one get visa for a 15-day-old?” says Bhomji, a daily wager.

In some huts around, low-power solar lamps have been lit, mostly to finish stitching assignments. “These can last till midnight if we don’t use them in the morning,” explains Karamshi.

Some distance away, the two bamboo shoots Tara Chand Bhil has placed parallel to each other,12 feet apart, are becoming indiscernible. But not to the 40-year-old.

“The shoots will form the base of my family’s new home,” he smiles.

Citizenship: The Numbers

- In 2016, the Centre empowered district magistrates and state home secretaries of seven states, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Delhi to grant citizenship to minority migrants. The states were selected as their border districts have a large number of persecuted minorities

- In July last year, MoS, Home, Nityanand Rai told the Lok Sabha that since 2016, 1,310 ‘minority migrants (Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian)’ had been granted citizenship by Rajasthan and district collectors of Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Jaipur. 1,113 of them were granted citizenship by the Jodhpur collector

- They were given citizenship either by nautralisation (having spent at least 11 years in India) or by registration (for persons of Indian origin who have been in the country at least seven years)

- In all, 605 migrants were granted Indian citizenship in 2015, 1,106 in 2016 and 816 in 2017

- Under citizenship rules, a district collector forwards the application to the state government within 60 days and the latter is required to forward the application to the Home Ministry within 30 days

- Citizenship (Amendment) Act cuts time limit for migrants who came to India uptil December 31, 2014, to become eligible for citizenship by naturalisation to five years. This covers Hindus, Christians, Sikhs, Parsis, Buddhists and Jains from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, leaving out Muslims

Apr 23: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05