- India

- International

Where Piyush Goyal is right: investments in infrastructure is different from money brought in to finance losses

It’s possible that the minister’s harangue against Amazon was aimed more at small shopkeepers and traders, the ruling BJP’s original support base, ahead of the Delhi Assembly elections.

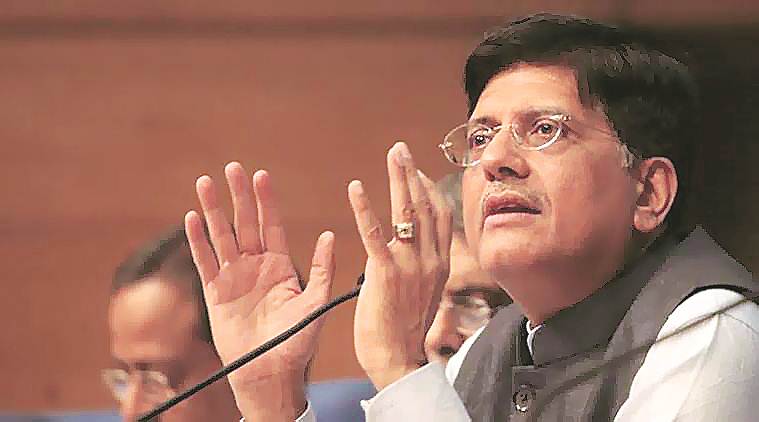

Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal said last week that the Amazon is not doing a great favour by promising to invest $1 billion in India. (File)

Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal said last week that the Amazon is not doing a great favour by promising to invest $1 billion in India. (File)

Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal courted criticism last week for his comment that Amazon wasn’t “doing a great favour” by promising to invest an additional $1 billion in the country. Both the statement (indiscreet, bordering on arrogance) and timing (when the $232.9-billion American e-commerce giant’s founder was visiting India) have certainly done no favour to an economy facing its worst growth, investment and jobs crisis in at least two decades.

Yet, Goyal has a point when he makes a distinction between investments by Amazon in warehousing and logistics infrastructure (“which is welcome”) and money brought in “largely to finance losses” (which “raises questions”). The latter part he elaborates by claiming that the Seattle-based retailer is losing $1-1.5 billion in India on a turnover of $10 billion (presumably the gross merchandise value of products sold through its online marketplace) due to “indulging in predatory pricing or some unfair trade practices”.

It’s possible that the minister’s harangue against Amazon was aimed more at small shopkeepers and traders, the ruling BJP’s original support base, ahead of the Delhi Assembly elections. But the basic concern — that the price points on many products offered on Amazon’s or Flipkart’s platforms are below even the cost price for ordinary brick-and-mortar retailers — is a valid one. If much of the new investments are only funding the losses from such deep discount sales, which are simultaneously undermining the operations of traditional kirana stores, it is a serious allegation.

The viability of mom-and-pop outlets — the country has an estimated 12 million of them — has primarily rested on three things. The first is low overheads: Kiranas are predominantly family-run enterprises employing one or two hands (“chhotus”), not paying rent on their own little shopping premises, and avoiding taxes by dealing in cash. The second is maximum space utilisation: The small retailer’s focus isn’t his store’s layout or appeal as much as ensuring the highest possible sales per square foot. That would mean packing, say, 200 items or SKUs (stock keeping units) within a 200 sq ft area.

But it is the third USP — high inventory turnover and working capital rotation — that is least appreciated. The real business of mom-and-pop stores comes from very fast-moving SKUs such as milk, curd, eggs, bread and vegetables. Take milk, where the neighbourhood grocer sells 100 litres daily. At an average maximum retail price (MRP) of Rs 50/litre and a margin of Rs 1.5/litre, his return on an investment of Rs 5,000 would be Rs 150. While that might seem small, our kiranawala is, however, getting back his Rs 5,000 (plus Rs 150) the same day for re-investing to buy and sell 100 litres the very next day. His cumulative return on a daily rotating capital of Rs 5,000 is, then, Rs 4,500 at the end of 30 days or Rs 54,750 over 365 days. A 3 per cent margin translates into an annual return that is nearly 11 times his capital investment.

The provision store-owner may, apart from the 100 litres milk, also sell about 25 litres of curd and butter milk/chhaachh (Rs 2-4 margin on MRPs of Rs 55-60 and Rs 20-25 per litre, respectively), five crates of eggs (Rs 15 margin on each 30-piece crate retailing at Rs 180) and 20 packs of bread (Rs 3 margin on an MRP of Rs 30). These articles of daily consumption are what keep our mom-and-pop stores going. By allowing rotation of capital almost 365 times a year, they generate good returns even on small margins, while making it possible for the kirana to also stock other less fast-moving items — both food (sugar, edible oils, dal, rice, biscuits, beverages, snacks) and non-food (toothpaste, soap, shaving cream, sanitary pads, washing powder, light bulb, stationary, broom).

The above business model of the traditional Indian grocery store, which is fundamentally efficient like our family-owned and managed farms, can be upended if subjected to unfair competition. The pioneering role of Amul, in procuring of milk directly from millions of farmers for processing and marketing to urban consumers, is well acknowledged. For the Rs 55/litre price of full-cream six per cent-fat milk that the consumer in Delhi pays, the farmer at Banaskantha in Gujarat today gets roughly Rs 43.9 (at a procurement price of Rs 710 per kg of fat) or close to 80 per cent. The rest is accounted for by the cost of chilling at the village collection centre (Rs 0.40), taking to dairy plant (Rs 0.50), processing (Rs 1.50), packaging (Rs 0.70), transportation from Banaskantha to Delhi (Rs 2.50), local distribution and marketing (Rs 2.50), advertising and other assorted expenses. This is a remarkably equitable and efficient system made in India, benefiting producers as well as consumers.

Not as well highlighted, though, is the part played by organised dairies, both cooperative and private, in providing livelihoods to mom-and-pop enterprises. Amul alone, for instance, has a network of a million retailers, in addition to its 3 million-odd farmers. Whether it is dairies, sugar mills or other food processing industries, the entire livelihood chain they support — farmers on one side and small grocers on the other — needs to be factored in. Retail is ultimately about margin, stock turnover and sales per sq ft — key metrics in which our kirana outlets, perhaps, fare as well or even better than an Amazon, Walmart or Reliance. Walmart’s average “days inventory outstanding” — a measure of how quickly stocks in its shelves turn into cash — is about 43, whereas the same would not exceed five days across all SKUs for the traditional stores. Where the kirana sector cannot compete is in scale and deep pockets.

India’s small retailers were badly bruised by demonetisation and the goods and services tax, while the ones in the mobiles and electronics business have simply been unable to take on Amazon or Flipkart. The Narendra Modi government is now seemingly trying to make amends. Goyal’s sanctimonious pronouncements are basically an outreach exercise to the BJP’s oldest constituency. By drawing a distinction between so-called genuine investment and investments to fund losses from heavily discounted sales, his government has put the big global e-retailers on notice.

40 Years Ago

EXPRESS OPINION

Best of Express

More Explained

Apr 18: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05