- India

- International

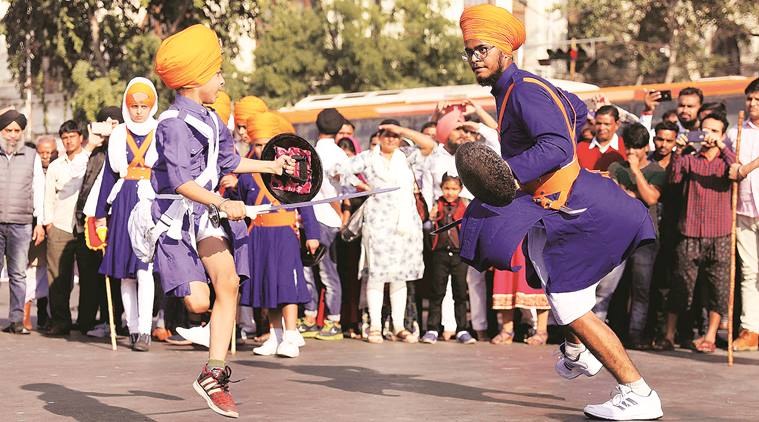

How Punjabi refugee dispersed into many corners of India, shaping national culture, and being embraced by friendship

'I grew up at the crossroads of many languages: Punjabi at home, Odia with my nanny, Hindi on the streets, and English at school. Which then is my mother tongue? What papers of authenticity will I be able to show? Where do I belong?'

After India’s Independence, a large number of Punjabi truck drivers took to the roads and highways. (Express Photo by Partha Paul)

After India’s Independence, a large number of Punjabi truck drivers took to the roads and highways. (Express Photo by Partha Paul)

(Written by Amandeep Sandhu)

For the rest of India, the Partition of India in 1947 is an abstract event fuelled by hate and kept alive for votes. But for those from Punjab and Bengal, it remains a lived reality. During Partition, Punjab lost more than half and Bengal three-fifths of its land. One million people died and 14 million were displaced. Many of these migrant refugees found their way into India beyond eastern Punjab and West Bengal. In many ways, this migration is why Punjabi food, clothes, music, and even cultural events have spread not only in the subcontinent but even beyond the borders of the nation-state.

Follow Live Updates of Republic Day

After India’s independence, a large number of Punjabi truck drivers took to the roads and highways. Their long and arduous travels, for instance, led to the mushrooming of dhabas to cater to their needs — again run mostly by Punjabis. Now, that food has travelled world-wide. From the 1940s to 1980s, the heavily Punjabi-influenced Hindi cinema spread its music to every corner of the nation. The state’s functional clothing, the salwar-kameez, has become a national attire.

The biggest challenge to the Punjabi migrant refugee experience, especially for the Sikhs, came in the year 1984: Operation Blue Star and the anti-Sikh pogrom. Contrary to the violence in the cow-belt, the experience of the migrants who came to Odisha and Chhattisgarh was different. Sixty-nine-year-old Hardaman Singh from Bhubaneshwar tells me why his family fled village Thuha Khalsa, near Rawalpindi in March 1947. As a Muslim mob attacked the village, women and children jumped into the well to escape the violence.

ALSO READ | 70 years of the Republic: Sunday Eye special on how our Constitution is a living, palpable force

“In 1947, my father was 19 years old. His father sent him to Madras (now Chennai) to work with one of the biggest contractors of the time. His other brothers went to the eastern and western regions of India,” he says. Why did the family not stay together? “My grandfather wanted his sons to spread out. He reasoned that if violence recurred in one part of the country, at least others would be safe,” he recalls. In 1957, Hardaman’s father moved to Bhubaneshwar and called his family over. “I have grown up in this city, lived here all my life. My family has no roots in today’s Punjab,” he says.

Given that a vast portion of Punjab’s land was lost in Partition, the migrants turned to opportunities in India. A huge number of Punjabis came to Odisha when the Hirakud dam, the Rourkela steel plant and the Paradip port were being constructed in the 1950s-60s. After these national projects got over, many stayed on as they entered trades like selling mechanical parts, small transport companies, civil work contracts, and so on.

My father, who worked on the Bhakra Nangal Dam, came to Rourkela in 1958. His reasons to travel 2,000 km was the desire to make a living but also the national mood: in Jawaharlal Nehru’s words, these projects “were the temples of modern India”.

At the release of my book in Bhubaneswar, a man walked up to me and asked if my parents had lived in Rourkela. His name was Aurobindo Behra. In 1984, he was the ADM Rourkela. On October 31, as mobs shouted slogans and nasty graffiti turned up on walls, he mobilised the police to take every Sikh family to the gurdwara. My childhood friend, Gagan Bains, remembers that timely intervention. “As soon as some rowdy elements threw stones at our home, our neighbours collected and told them to buzz off. The neighbours insisted we stay back but the police escorted us to the gurdwara. In our absence, the neighbours took care of our garden, our pet Pomeranian, and returned us the cash we had left with them for safe-keeping.”

ALSO READ | Why January 26 was chosen to be the Republic Day

When I tell these stories to Hardaman, he is not surprised. “My father was then the president of the gurdwara in 1984. Then chief minister JB Patnaik called him up and told him not to worry; he would ensure no Sikh is harmed. Though Bokaro, Ranchi burnt, nothing happened here or even in Rourkela. His concern was his state, his people. He defied his party’s high command. The current chief minister Naveen Patnaik’s mother is a Sikh. That is why north Indians remain safe. Two of the biggest business houses in Bhubaneswar are the Narula and the Hans families. They too are Partition refugees who started small.”

When my father took voluntary retirement in 1991, he chose not to return to Punjab but settle down in Durg, in then Madhya Pradesh, now Chhattisgarh. His reasons were: Punjab was in the throes of militancy, his friends were in Bhilai, and he felt safe in eastern India. My father’s best friend’s son Kulvir Singh tells me, “In 1984, unlike your parents in Rourkela, we in Durg did not even leave our homes.” After an MBA, Kulvir chose to get into his father’s business in Durg. “I like going to Punjab once in a while but this is home to me.”

What makes it home? He reminds me of his and my childhood. “That group of children cut across class and language divides. There were kids of officers, of workers, of maids, of local business families. We were from Punjabi, Odia, Telugu, Tamil, and Hindi-speaking families. That diversity shapes my understanding of India.”

These PSU towns saw some of India’s first experiments with nuclear families, where neighbours came from different parts of India, where our tongues got mixed. This was what India sought when it started its “tryst with destiny”, to quote Nehru again.

With rising nationalism, the prospect of a National Register for Citizens (NRC), in which documents are the basis for citizenship, I wonder where I stand. I was born in Rourkela, I live in Bengaluru. I have neither land records, nor my parents’ birth records. To which region do I belong? I grew up at the crossroads of four languages: Punjabi at home, Odia with my nanny, Hindi in the streets, and English at school. Which then is my mother tongue? What papers of authenticity will I be able to show?

It is also important to note that Punjabi migration in the east was a middle-class experience. The very dams, ports, steel plants and industry that were supposed to benefit the region have still not benefitted the tribal people whose lands were occupied. The Punjabis came here with a job or strove under the benign gaze of the state to become middle class. Our experience of citizenship is positive but the same cannot be said about the original inhabitants of these states – the tribal people. That is why, the real issue here is not communalism but organised corporate loot abetted by the state. Solving this inequity needs a framework of justice that the current citizenship-related politics does not address and, perhaps, never will.

The writer is the author of Panjab: Journeys Through Fault Lines

Apr 19: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05