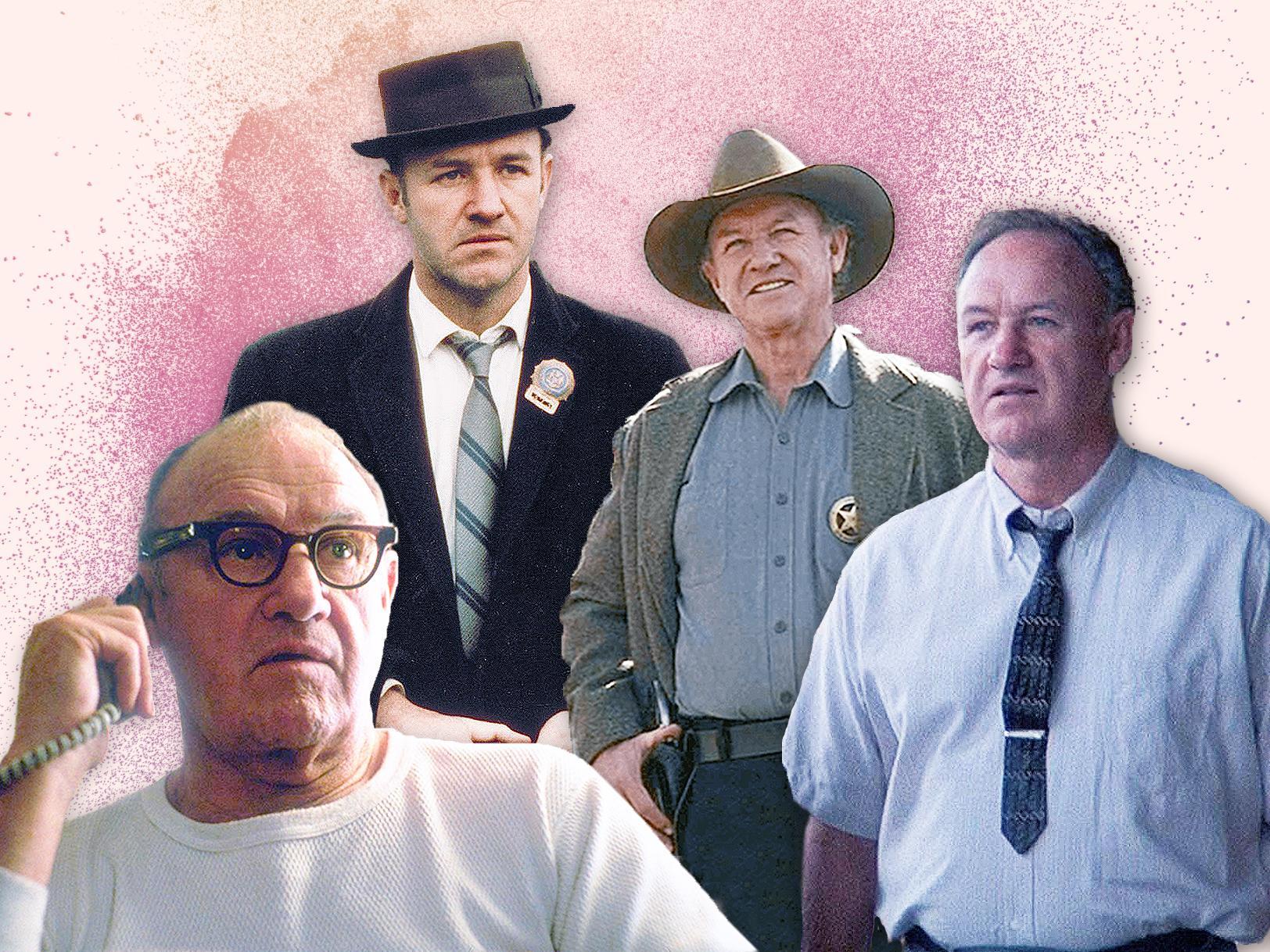

Gene Hackman: The tormented, brawling genius of film

Despite being voted ‘Least Likely to Succeed’ by his acting school classmates, Hackman has become one of the greatest actors of our age, writes Martin Chilton

Gene Hackman joked that he was “at least seventh choice” to play Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle in The French Connection. After years of struggle and misfortune, the role of the gritty New York detective won him an Oscar at the age of 41 – and made him a star.

Hackman, who celebrates his 90th birthday on 30 January, had a remarkable career, spanning 85 movies and acclaimed roles in television and on stage. Yet success came only after numerous crushing disappointments. Many aspiring actors would have given up, but tough former marine Hackman said he held on to his conviction that “I wasn’t going to let any f***ers get me down”.

The actor, born Eugene Alden Hackman in San Bernardino, California, in 1930, learnt resilience at just 13. His father walked out on their family for good. “He always went too far, laid it on pretty heavy,” recalled Hackman of his dad, who operated a newspaper printing press and believed in corporal punishment. Things came to a head in 1943, after the family had been forced to relocate to Denville, Illinois, and live with grandparents.

The fateful day Hackman’s father abandoned his family remained forever etched into Hackman’s mind. The actor often talked in later life about the “hurt and disappointment” of the memory of his father waving from the car as he drove past him on the street. “That wave, it was like he was saying, ‘OK, it’s all yours. You’re on your own, kiddo’,” Hackman recalled in The New York Times Magazine 46 years later. He drew on the emotions of that fateful day in his career, quipping that “dysfunctional families have sired a number of pretty good actors”.

The 40 best films of the decade

Show all 40As a teenager, part of a single-parent family that moved about a lot, Hackman was frequently in trouble. He rowed with authority figures at Storm Lake High School in Iowa. He even spent a night in jail after stealing candy and a bottle of soda. His most peaceful times were when his movie-loving mother Anna took him to the cinema to watch his beloved James Cagney, a hobby that sowed the seeds of his future ambitions.

Hackman finally left school after a furious row with his basketball coach. After working for a brief spell in a steel mill, he lied about his age so he could join the Marine Corps at 16, “looking for adventure”. He spent four and a half years in the marines – serving in Japan and undergoing missions in China during Mao’s revolutionary years. His proclivity for trouble was not cured by wearing military uniform, however, and he got into trouble for brawling. “I have trouble with direction, because I just have always had trouble with authority,” he told Larry King in 2004. “I was not a good marine. I made corporal once and was promptly busted.”

Fate intervened just as his battalion was called up to fight in the Korean War. Hackman crashed a motorcycle into a tractor that had no lights, breaking his right leg, right shoulder and left knee and leaving him unfit for active service. After being discharged in 1952, Hackman spent six months studying journalism at the University of Illinois before dropping out. At the age of 22, he made his way to New York to try to be an actor, bolstered by the taste of show business he had sampled as a marine, when he had been a disc jockey and news announcer on Armed Forces Radio Service.

Hackman would later ruefully recall the dark days of his early twenties, scuffling around miserable jobs, and living at the YMCA in New York. He drove trucks, worked as a shop assistant at a drugstore (“customers treated you like crapola”), sold confectionery door to door, worked in an upmarket women’s shoe department (where he would slip expensive shoes to friends in exchange for a few dollars) and hauled furniture up high-rise apartments. The worst job, he said, was the night work at the Chrysler Building, polishing leather furniture.

What Hackman described as the “turning point” of his life came in 1955 when he was a doorman at a Times Square hotel. A marine sergeant who had been his drill instructor happened to walk past, dressed in his full colours. “He never looked at me but muttered, ‘Hackman, you’re a sorry son of a bitch’,” he told David Letterman. Hackman was “so embarrassed” by the way he was earning a living that he redoubled his efforts to make it as an actor.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Things began to change in 1956. On New Year’s Day, he married his girlfriend Fay Maltese, a bank secretary, and she encouraged him to pursue his dreams. They moved back to California, where Hackman enrolled at the Pasadena Playhouse Theatre’s acting school. “I was not considered one of their most promising students,” Hackman recalled drolly in a 1987 interview. He was putting it mildly.

At 26, he was more than five years older than most of his fellow students, whom he regarded as tanned young “walking surfboards”. Hackman, who was 6ft 2in, thought of himself as “big lummox kind of person”, talking self-deprecatingly about having the face of “your everyday mine worker”. His classmates did not rate him. The only person he liked was a small, 19-year-old oddball who strolled around in a suede vest and sandals. The rest of the class were hostile to him, too, calling him a “beatnik”. That friend was Dustin Hoffman.

The future Oscar winners bonded over their dislike of their fellow students. “Dustin was thought of as amusing and strange,” Hackman recalled in 1998. “I’d been in the Marine Corps for five years and was married – an equally unlikely candidate for movie stardom.” Hackman and Hoffman would escape their classmates by going up on to the roof of the theatre to play bongos.

The class alumni voted them both “Least Likely to Succeed”. Hackman was thrown out of the Playhouse after a year, having been awarded the lowest ever grade given there. In later years, he tended to frame these experiences in humorous terms, joking about failing to hear from his old classmates. In 2001, Hackman recalled that after his own acting career had started to take off, he had run into one former classmate who boasted about being in an episode of a TV drama called Blue Light. “And it’s gonna be repeated,” he told Hackman. Blue Light was axed in 1966 after only one season – the same time Hackman landed his first big film role in Bonnie and Clyde.

Being voted “Least Likely To Succeed” only fuelled Hackman’s determination. Back in New York, he began studying twice a week with George Morrison, a graduate of Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio, who taught him about “method acting”, relaxation techniques, how to hone his timing and delivery and overcome his insecurities. “Gene never knew whether he was an actor,” Morrison told Vanity Fair in 2013. “He would have a part, and then go back to moving furniture.” Hackman did, however, take on board two fundamental questions Morrison said he should dwell on for every part: “How am I like this person?” and “How am I not like this person?”

The battle to get on to Broadway was arduous – “No one starts at the top in the theatre,” he said, “and the bottom is a very ugly place” – but he gradually began to get promising parts, making decent money for the first time. His biggest disappointment was that his mother, who died in 1962 when her burning cigarette ignited a fire in her home, was not around to see him fulfil his dreams. Even as an old man, Hackman would talk wistfully about a trip to the cinema with her, when she said she hoped “to see you do that someday”.

In 1964, the year he appeared in the popular comedy stage show Any Wednesday, Hackman landed a role in Lilith, a movie with Warren Beatty. A couple of years later, Beatty recommended Hackman for the role of Buck Barrow, elder brother of the outlaw Clyde Barrow. Hackman’s performance in Bonnie and Clyde, which captured the anger and rebellion of Buck, won him an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor, although he lost out to Cool Hand Luke’s George Kennedy.

In his thirties, Hackman remained obsessive about improving his skills. He would wander around New York, endlessly watching people, absorbing their personalities and mannerisms. He also drew on emotions about the people close to him, admitting that he did so “in a very cold and clinical way”. Director Arthur Penn said Hackman was one of the best at exploiting the early pain in his life. “He’s one of the ones who are willing to plunge their arm into the fire as far as it can go,’’ said Penn, who directed Hackman in Bonnie and Clyde and Night Moves (1975).

There is a compelling scene in Clint Eastwood’s 1992 western Unforgiven, in which Hackman portrayed the sadistic Sheriff Daggett. Hackman’s character brutally beats a hired gunman called English Bob, played by Richard Harris. When asked how he found inspiration for this scene, he said he channelled anger over a snub from Harris. The pair had appeared together in the 1966 film Hawaii. “I could tell he didn’t remember having worked with me and he tried to fake his way through it,” Hackman told The New York Times in 2001. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh, I can use this.’ I just took that disappointment and did this kind of transference.” He won an Oscar for his performance.

Two decades earlier, as Popeye Doyle, Hackman had found having to be violent on screen so gruelling that he told French Connection director William Friedkin “he should consider replacing me”. But it is strange, given Hackman’s personal history of fights with strangers, that he had such qualms about slapping around a drug suspect on screen. Hoffman said that his friend would sometimes just announce, “I gotta go,” explaining to Variety that “he had to get in a fight. He’d go to some bar.”

He was still getting into real-life violent altercations as an old man. In December 2001, a minor traffic accident in West Hollywood escalated into a fist fight with two men in broad daylight. “He brushed against me and I popped him,” Hackman told the Los Angeles Times. “Then the other guy jumped on me. We had this ugly wrestling match on the ground. The police came ... I got a couple of good shots in. The guy had me around the neck. That’s the ugly part. When you’re down on the ground and you’re nearly 72 years old.”

Hackman is truly a man of wild contradictions. Robert Duvall, who has been a friend since the 1950s, called him “a tormented guy, always into his own space, his own thing”. Where director Arthur Penn saw a man normally full of “great joie de vivre”, Morrison saw an inveterate “loner”. Hackman’s volatile bust-ups with directors on set earnt him the nickname “Vesuvius” – although he was forgiven for his temper tantrums. “There’s something very charismatic in him, even when he’s being his worst,” said Wes Anderson, who directed Hackman in The Royal Tenenbaums.

The paradoxes of his life are plentiful. His political views were liberal; he was a lifelong Democrat voter who was proud of being listed as an “enemy” of President Nixon. Yet Hackman also loved arch conservative Ronald Reagan, saying: “I loved the idea of that man. He was so committed to a beautiful America.”

He is as happy talking about his beloved Jacksonville Jaguars football team as he is about art. Hackman started painting impressionist oil works in the 1950s, shortly after taking a class at the Art Students League Of New York. At the height of his fame, the Oscar winner steered clear of “shallow” Hollywood parties, preferring instead to spend his spare time stunt flying and deep-sea diving. In the late 1970s, Hackman drove in Sports Car Club of America races and even competed in a 24-hour sports car endurance test in a Toyota he shared with leading Japanese racer Masanori Sekiya.

Hackman’s hobbies, though, were always secondary to his devotion to his craft. His greatest roles – including his two films as Popeye Doyle and the monumental way he portrayed the drug-withdrawal scenes in French Connection II – have earnt him a stellar reputation among his peers. “Gene was simply the best actor I worked with,” said double Oscar winner Kevin Costner.

Hackman’s popular roles included playing sneering supervillain Lex Luthor in the Superman films, but the former stage actor always thrived on taking on challenging parts in movies, including playing a widowed college professor in 1970’s I Never Sang for My Father, a role that earnt him a Best Supporting Actor nomination. He was nominated again for his gripping portrayal of FBI agent Rupert Anderson in Mississippi Burning (1988), and is also saluted for major contributions to hit movies such as The Firm (1993), Get Shorty (1995), Enemy of the State (1998) and The Royal Tenenbaums (2001).

However, two of his finest roles came in films that had little commercial success. In the picaresque road movie Scarecrow (1973), which Hackman described as his favourite movie he worked on, he and Al Pacino played a pair of ex-con hobos who dream of opening a car wash. “It’s the only film I’ve ever made in absolute continuity, and that allowed me to take all kinds of chances and really build my character,” said Hackman.

Hackman had the ability to laugh at his own celebrity status at this time. He and Pacino prepared for Scarecrow by staying in costume and character while they spent time on the streets of San Francisco. Hackman told David Letterman about asking a muttering homeless man on Market Street the way to the nearest soup kitchen. The man gave them comprehensive directions. After they thanked him, in gruff voices, the homeless man smiled back and replied, “You’re welcome, Mr Hackman and Mr Pacino.”

Perhaps Hackman’s finest performance was as the bugging expert Harry Caul in The Conversation (1974). Finding out that he was second choice to Marlon Brando seemed to inspire him to even greater heights. The prescient script about illegal wire-tapping, written by director Francis Ford Coppola several years before Nixon’s Watergate scandal, reveals Hackman’s brilliance as a character actor, playing such a secretive, introverted man. “That was the pinnacle of my acting career in terms of character development,” Hackman said. “Caul was somewhat constipated. The character didn’t burst out. There was no satisfying cathartic moment in the film.”

As well as reaching dizzying heights in acclaimed movies, Hackman also admitted to Costner that he had taken many “questionable roles”, in substandard films such as The Poseidon Adventure (1972), Lucky Lady (1975), A Bridge Too Far (1977) and March or Die (1977). In the late 1970s and 1980s, Hackman also ran into problems with tax liabilities, joking that he had to borrow his daughter’s “piece-of-s***” car to get to interviews in Hollywood, having blown money on expensive motor vehicles, private planes and bad investments. “I was just barely hanging in, taking pretty much anything that was offered to me and trying to make it work,” he told interviewer Alysse Minkoff in 2000. He had also been left devastated when his best friend Norman Garey shot himself in 1981. Five years later, his troubled marriage to Faye, with whom he’d had three children, ended in divorce. It was a terrible time for Hackman, who admitted he was struggling to find the motivation to act.

It says everything for Hackman’s character and true greatness as an actor that he pulled himself together to make his award-winning appearance in 1988’s Mississippi Burning after such a troubled period. “He is incapable of bad work,” said the film’s director, Alan Parker. “Every director has a short list of actors he’d die to work with, and I’ll bet Gene’s on every one.”

Hackman has always been a voracious reader, and alongside his acting, he also carved out a career as the co-author of historical fiction. After bonding with his New Mexico neighbour and undersea archaeologist Daniel Lenihan – they shared a deep love for the books of Robert Louis Stephenson, Herman Melville, Ernest Hemingway, Joseph Conrad and Jack London – the friends came up with the idea for a novel called Wake of the Perdido Star, a 19th-century sea adventure no less. They went on to write four more books, including a western thriller. Hackman says the hardest thing about writing fiction is the constant editing. “I like the loneliness of writing, actually. It’s similar in some ways to acting, but it’s more private and I feel like I have more control over what I’m trying to say and do.”

Hackman retired from acting in 2004 after a final role in Welcome to Mooseport, a satire in which he played retired president Monroe “Eagle” Cole. As an older man, he found the acting business “very stressful” and was no longer willing to make “the compromises that you have to make in films”. He later joked that he would only take another movie role if it was filmed in his house.

Since then, aside from narrating a documentary called The Unknown Flag Raiser of Iwo Jima in 2016, Hackman has been content to live quietly in Santa Fe with his second wife Betsy Arakawa, a former classical pianist 32 years his junior. Despite heart concerns (Hackman had angioplasty surgery in the 1990s) and knee pains that are a legacy of that bike crash, the Hollywood star continues to get out and about on his bicycle. Even a collision in 2012 in Florida – when, with no helmet on, he was struck by a pick-up truck and injured – has not dampened his spirits. In January 2018, Bicycling.com reported that 88-year-old Hackman had bought a $2,800 e-bike, capable of travelling at 20mph, so he could ride around Santa Fe.

Celebrity worship has never been something Hackman wanted in his life. He says he is “not a sentimental guy” and does not keep movie memorabilia in his home – apart from a poster of Errol Flynn. He isn’t even sure what happened to his Oscar statues. “Maybe they’re packed somewhere,” he told the LA Times in 2001.

After retiring, Hackman was amused rather than angry when – unlike the homeless man in San Francisco in 1973 – a film crew in his home town failed to recognise him. “There was a young assistant director on a backstreet in Santa Fe, directing traffic,” he said in 2011. “I pulled up next to her and asked her if they were hiring any extras. She said, ‘No, I’m very sorry, sir.’”

Hackman once said that he wanted to be remembered as “a decent actor – as someone who tried to portray what was given to them in an honest fashion”. He did so much more than that. Hackman is simply one of the greatest actors of our age – even if he did become “least likely to succeed as an elderly extra”.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies