The last couple of years have produced a lot of books about Russia. Many, if not most of them, argue that Donald Trump’s election was a plot by Vladimir Putin, and feature a Russian stereotype or three on the jacket – St Basil’s Cathedral, a nesting doll, letters turned round – to make the connection between the two presidents visual. Many cover the same ground, blaming Trump on the Kremlin’s omnipotent and steely-eyed dictator, rather than on any deep currents in American society. This book is not like that.

Joshua Yaffa is a humane, gifted, curious-minded American journalist who has lived and worked in Moscow for the past seven years, many of them as a correspondent for the New Yorker. Between Two Fires is his rich and detailed examination of how Putinism works, about the compromises required by individuals who want to get ahead, and the capricious nature of the system Putin inherited then moulded in his own image.

The country he describes is a world away from the stereotypical dictatorship that emerges from the brains of more excitable writers. Putinism is far less pernicious than it is often made out, which is what is so pernicious about it. Each chapter of Yaffa’s book has a new main character – the head of the country’s largest broadcaster; an Orthodox priest; a doctor who helped homeless people – and each acts as a mini-biography, tracing how that individual responded to the pressures of making a career, and seeking to make a difference or get ahead in Russia’s unique political culture.

Some Russians do not compromise with their government. They have principles and live by them, as dissidents did in Soviet times. But most Russians seek to navigate the system, to bend themselves to its requirements, and to realise their dreams within its structures. Yaffa’s gift is not immediately to condemn them for that, but to seek to understand the pressures that led them to cooperate with the Kremlin, to evaluate what they gained from doing so, and what they lost. “I became convinced,” he writes, “that the most edifying, and important, character for journalistic study in Russia is not Putin, but those people who habits, inclinations, and internal moral calculations elevated Putin to his Kremlin throne and now perform the small, daily work that, in aggregate, keeps him there.”

This pointillist approach to describing Russia has been used before, most notably by Andrew Meier in Black Earth, as well as by Yaffa’s boss at the New Yorker David Remnick, in his classic Lenin’s Tomb. But that’s not to condemn Yaffa for doing it again; it is a highly effective way of addressing a country that is so big and so diverse that the only other way to capture it in a single volume is to generalise so widely as to lose all human interest.

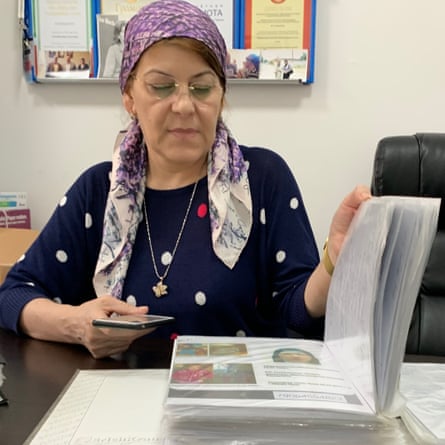

Perhaps the most shocking chapter describes Heda Saratova, a Chechen human rights activist, and her journey from 1999, when she was trapped in Grozny while a military campaign begun by Putin smashed the city around her, to now, when she is a cheerleader for Putin’s hand-picked warlord. In Yaffa’s account this was a journey not of one appalling transformation, but of many smaller evolutions, each one barely perceptible. If she wanted to do good, she needed to work with the powerful; if she wanted to save people, she needed to know who to ask for salvation. Her colleagues refused to make the compromises she did, and therefore perhaps failed to assist all the people she managed to help. But, after two decades of accommodation, she had so lost her moral compass that she would excuse torture and murder, in the name of human rights.

Other chapters do not show such a stark journey, but all of them share the same pattern – idealism, compromise, outcome – and it explains much about how Russia functions. The Russian state is the source of overwhelming power so, to effect change, you have to work with it. But, by working with it, you prevent any other alternatives from emerging, whether that be political parties, the media, charities, or anything else. And you have to compromise your own ideals in the process.

One of Yaffa’s chapters updates a story I have told. For me, the creation of an independent museum on the grounds of the old Perm-36 gulag camp was a sign of hope, of a new Russia growing from the ashes of the old. Yaffa goes back to see what happened next, and comes to a very different conclusion. He tells the story of the camp’s directors being squeezed out, of it being taken over by bureaucrats, and being forced to adapt its historical message to the political realities it is in. History, like everything else, must serve the Kremlin.

Perhaps Yaffa’s most striking achievement is that every compromise he describes is completely understandable, yet cumulatively their effect is disastrous. The plural of compromise turns out to be corruption. This is a measured, clever, well-researched and superbly written work. It won’t sell nearly as well as the books explaining how Trump has been a KGB agent for 30 years, but it will be read long after they’re deservedly forgotten.