The first time you see Joby Weeks work his magic, you might wonder what the hell is going on. Here he is, serving up financial advice on stage in Acapulco or Aspen or some other place where millionaires roost, and he’s dressed like a frat boy, in cargo shorts, a T-shirt and sandals. He giggles, snorts and waves his arms, as if he’s herding pledges to an endless supply of Jägerbombs.

But this 38-year-old bro can sell. As he settles into his pitch, it becomes clear that his attire is ideal for the task at hand. It screams casual, comfy, I-don’t-give-a-rat’s-ass sincere. It’s the antithesis of the uniform of Wall Street corporate tools, the pinstripe suit and Hermès tie and John Lobb wing tips. It’s what a bro would wear 365 days a year if he was absurdly rich and didn’t have to impress anybody. And what Weeks is selling, to some extent, is his own legend: The Secret of How to Be Me.

LIVE A GREAT STORY, one of his T-shirts proclaims. And what greater story is there than the carefully cultivated success story of Joby Weeks?

It goes something like this: Colorado teen of modest means, bitten by radioactive ambition, turns into amazing super-entrepreneur, hawking nutritional supplements. Becomes a millionaire at age 19 — or 21 or 23, depending on when the story is being told. Gets into Bitcoin, e-cigs, renewable energy, marijuana legalization, Ron Paul. Gets richer, rich enough to spend his days in perpetual motion, traveling the globe in search of adventure and posting photos of his journeys on his brand-building website, WeeksAbroad.com.

Here’s Joby, dune-buggying across the Sahara. Snowboarding down Mt. Elbrus in Chechnya. At the South Pole, planting the flag of Liberland, a largely hypothetical country beloved by libertarians. Cruising around St. Kitts, Machu Picchu, Reykjavik, Tokyo, the Cook Islands — dozens of countries and more than a hundred cities a year, almost never spending more than a week in one place. In 2018, Weeks and his wife, Stephanie, took their newborn daughter, Liberty, to all 50 states in 42 days, setting a new record for infant peripateticism. By the time she was thirteen months old, Liberty had visited 45 countries on four continents.

Amid all this globe-trotting, Weeks emerged as the most visible spokesperson for BitClub Network, a venture that promised to make the rarefied world of cryptocurrency available to the masses. For a $100 membership fee and an investment as low as $500, BCN clients could purchase a share in a Bitcoin mining pool; the money was supposed to go toward acquiring and operating stacks of high-speed computing equipment to be used in carving out new blocks of transactions in the Bitcoin blockchain. “Miners” who solve the complex computational problems involved in that process are rewarded with newly issued Bitcoin. Weeks likened the BCN pool to “buying the goose that lays the golden egg,” rather than simply purchasing a few golden eggs’ worth of bitcoins.

“We’re basically selling machines that print money,” he told one audience in 2017. “Whatever the data center generates each day is paid out to our investors in a daily dividend. … We’re paying these people in Bitcoin every single day.”

The pitch was a tempting one, particularly at the peak of the Bitcoin frenzy a few years ago. (The value of a single bitcoin reached close to $20,000 in late 2017, but a sell-off sent the price plummeting; it’s now back up around $10,000.) Machines that print money! Fractions of bitcoins trickling into your account every day, financing your own cargo-short sorties to the Bahamas, the Seychelles, or some other Joby-like place…. It was a fine daydream, and more than a few of Weeks’s spellbound listeners bought into it.

The dream blew up a few weeks ago, with the arrests of Weeks and three other men on charges of wire fraud and selling unregistered securities. The federal indictment characterizes the BitClub Network as an elaborate scam that conned hundreds of thousands of investors out of “at least” $722 million, making it one of the largest cryptocurrency frauds ever.“We are building this whole model on the backs of idiots.”

tweet this

While the BCN promoters bragged that they had “the most transparent company in the history of the world,” a venture that was “too big to fail,” prosecutors accuse them of operating an updated version of a classic Ponzi scheme — making exaggerated claims about mining capability they didn’t have, doling out inflated earnings to early investors in order to rope in more suckers, and taking huge rake-offs for themselves, much of it in the form of commissions from a multi-level marketing setup that offered investors bonuses for recruiting new members.

In addition to its brazenness, the scheme was notable for the unbridled contempt that some of the participants expressed for the marks who forked over their money. One of Weeks’s co-defendants, Matthew Goettsche, a 37-year-old Colorado resident, was involved in the launch of BCN in 2014. According to internal emails and online chats obtained by federal investigators, Goettsche urged the company’s computer programmer to provide fake proof of mining power, to “bump up the payout,” and later to “drop mining earnings significantly” so that the operators of BCN could “retire RAF” — rich as fuck. Goettsche described the company’s target audience as “the typical dumb MLM [multi-level marketing] investor.”

“We are building this whole model on the backs of idiots,” Goettsche explained to the Romanian programmer, Silviu Balaci. And, in another exchange with Balaci: “We can make up the numbers any way we want to appease auditors.”

His attorneys say Joby Weeks didn't know about the scamming inside BitClub Network, despite being the company's top seller.

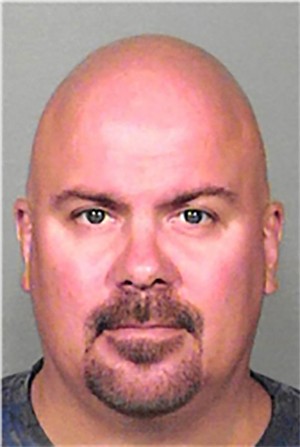

Korey Rowe

Prosecutors have argued against granting the defendants bail before trial, contending that their wealth, global connections and other considerations make them heavy flight risks. Goettsche, for example, bought an island in Belize for $6.4 million in 2017, owns his own plane and, along with Weeks, has sought to obtain citizenship in St. Kitts.

“Goettsche likely had access at various points of the scheme to hundreds of millions of dollars, and he has used entities, properties, law firms, and cryptocurrency exchanges, among other methods, to make tracing those millions incredibly complicated,” one government pleading states. “His access to wealth from anywhere in the world is so overwhelming [that] there is no combination of conditions that would make fleeing the country anything more than a minor inconvenience.”

Goettsche’s attorneys have responded that there’s nothing inherently sinister about seeking citizenship in St. Kitts, which has an extradition treaty with the United States. “It’s common for U.S. citizens working in the digital currency industry to obtain dual citizenship,” they contend, because some cryptocurrency entities won’t do business in the highly regulated U.S. market. They also say that BCN was engaged in more extensive mining operations than federal prosecutors seem inclined to admit.

Weeks’s attorneys have weighed in, too, maintaining that their client was as much in the dark about the scam at the heart of BCN as any clueless investor. Although sometimes identified in public presentations as a “founder” of the company, Weeks was not in on the ground floor, like Goettsche, and apparently had no access to BCN accounts; he’s described himself as one of dozens of promoters of the mining pools, not an operator.

“There’s no question that he was not in a real management position,” says Korey Rowe, a filmmaker who traveled with Weeks for a year, working on a documentary about his far-flung adventures. “He was the number-one seller in the company, but he didn’t know it was designed to be a fraud. He believed avidly that this was a legitimate MLM and not a Ponzi scheme.”

It’s ironic, of course, that something as supposedly inviolable as Bitcoin, a digital currency untethered from the corporate banking system and subject to meticulous, independent verification of each transaction, should become such rich ground for scams and frauds. But ever since the “genesis” block of Bitcoin was first mined eleven years ago, there have been convoluted efforts to game the system, along with cryptocurrency empires that were too big to fail but did. The collapse of BCN adds more confusion to the scene, blurring the line not only between legitimate mining pools and scams, but between the con man and the dupe: Did at least one of the hucksters involved actually buy into the dream he was peddling, the golden goose and the machine that prints money and all the rest?

“The other guys, I think they’re trash,” says Rowe. “I think they set up a company to defraud people, and they should spend every day in jail. But Joby’s not them. He didn’t do that.”

Joby and Stephanie Weeks chronicled on a website their world travels, spanning hundreds of cities and dozens of countries.

WeeksAbroad.com

Joby’s great-great-grandfather, John W. Weeks, was a U.S. senator and served as Secretary of War during the Harding and Coolidge administrations. Sinclair Weeks, John W.’s son, was Eisenhower’s Secretary of Commerce, and his point man for building the interstate highway system.

Joby’s father, Nathaniel Weeks, bucked a family allegiance to Harvard; he went to Dartmouth and became a teacher at a Christian school in Arvada. It wasn’t a high-paying or glamorous job. (“We didn’t believe in miracles; we relied on them,” Joby later quipped.) Joby has credited his dad with introducing him to the work of Ayn Rand and a go-getter work ethic. In his teens he became a skillful barterer, swapping a $25 guitar for a $250 car stereo, cashing that in for a $1,000 home theater system, and so on. He also started buying M&Ms in bulk at Costco and selling them door-to-door at a substantial mark-up.

It wasn’t quite as Horatio Alger as it sounds. “I had that rebellious spirit in me,” Joby told one TV pastor in 2004, recalling his brief career as a “street pharmacist,” busted for smuggling drugs in Costa Rica at age sixteen. Court records indicate that he was also charged as an adolescent with obstructing the police and assault, and that he had two DUI arrests in his twenties.

Joby attended Faith Christian Academy, the Arvada Covenant Church, and summer camp at Summit Ministries before moving on to Pomona High School. He enrolled in the University of Colorado but dropped out before his first class. He didn’t see any reason to waste his time studying to be a wage slave when he’d found something better.

For years, his mother, Silence Weeks, a respiratory therapist, had sought to increase the family’s income through direct sales on behalf of different multi-level marketing firms. Her side business took off after her brother-in-law, physician Bradford Weeks, introduced her to Mannatech, an MLM powerhouse with a product line of dietary supplements and a far-flung network of sales associates. Before long, Silence had become one of the company’s top sellers, and Joby was developing his own sales network.

Mannatech has proven to be one of the most durable companies in the booming nutritional-supplement business; at one point, former presidential candidate Ben Carson was appearing in the company’s testimonials, though he later downplayed the relationship. Scientists have questioned the therapeutic value of its pricey products, and the company has occasionally landed in litigation because of overreaching claims by its sale force of independent contractors, some of whom have suggested that the supplements can cure cancer, AIDS, autism or asthma. (The man who took Mannatech to the Weeks family has also come under attack, for different reasons. In 2013, Brad Weeks had his medical license suspended by Washington regulators after he allegedly prescribed human growth hormone to several patients as an anti-aging therapy; Dr. Weeks has challenged the action as unjust. The long-running dispute prompted Nat Weeks to write to Carson, now a member of Donald Trump’s cabinet, to complain, “This is the oppression we elected Trump to defang.”)

In a recently filed court document, Nat Weeks notes that Joby “by age 19 was earning $6000 every 28 days as an independent contractor with Mannatech” — a sizable income for a teenager, but hardly millionaire territory. It’s possible that he made his first million by 21, or 23, as he later claimed. His array of interests and investments continued to expand — from MLM projects and green-energy hustles to libertarian causes (he stumped for Ron Paul) and Colorado’s Amendment 64, legalizing recreational marijuana. By the time he married Stephanie, a dental hygienist, a decade ago, the couple could afford to adopt their whirlwind travel schedule, taking occasional time-outs for snowboarding back in Colorado and charity work.

Joby also became an early investor in cryptocurrency. Having a foolproof way to move assets around without reliance on governments or banks would seem to be a no-brainer for a perpetual traveler of his caliber, but he wasn’t an instant convert. His YouTube pitches for BCN usually include the story of how he bought his first 250 bitcoins for $200, then promptly forgot about them. A year later, he says, he logged into his digital wallet and saw that his purchase was now worth close to $50,000.

Actually, the rise in the price of a single bitcoin from less than a buck to around $200 took almost three years — a little detail that’s easily lost in the shuffle as Weeks’s wide-eyed audiences mentally calculate the current seven-figure value of 250 bitcoins. But Weeks wasn’t interested in simply stashing away a few bitcoins; he saw the phenomenon as part of a revolution in the global economy, one that would provide startling new opportunities for canny entrepreneurs."I guess most people do not know only 40 percent is used for mining and the rest for commissions."

tweet this

He became a high priest of crypto, a featured speaker at conferences of the like-minded — a gaggle of self-proclaimed anarchists, radical capitalists and digital messiahs. He became so enamored of one such annual gathering, the Anarchapulco confab in Acapulco, that he paid $4 million in Bitcoin for a thirteen-bedroom mansion there with an ocean view. And his journey led him to the BitClub Network, an enterprise that appeared to combine two promising revenue streams: Bitcoin mining and an MLM sales structure.

Weeks got involved in BCN in the summer of 2015, after the company had already been operating for almost a year. Federal investigators were able to trace the origins of the scheme through online discussions between Silviu Balaci and Matthew Goettsche stretching back to early 2014.

Goettsche, a 2005 graduate of CU, wasn’t well known in Bitcoin circles, but he had a strong background in network marketing projects. Online references suggest that at one point he was involved in the distribution of Waiora, a line of nutritional and detox products that, like Mannatech, has its share of detractors; one lawsuit claimed that the company “sold a mineral-enhanced anti-aging product that, in reality, contained little more than water.” According to court records, Goettsche played a major role in shaping the revenue structure of BitClub Network, which called for splitting the investors’ money three ways: 20 percent for operating expenses, 40 percent for commissions, and 40 percent going to pay for mining equipment.

“I guess most people do not know only 40 percent is used for mining and the rest for commissions,” Balaci observed.

“The leaders know,” Goettsche replied. “It’s the sheep that don’t.”

How much Weeks knew about the arrangement is a key question in the current criminal case. He hadn’t been with the company long when he complained that BCN wasn’t “transparent enough for the big money guys.” And he seemed troubled by how little of the investors’ money was going to actual mining.

“We can’t just ‘sell’ people mining hardware [shares] in BitClub and then not use the money to buy equipment,” he wrote in an email to Goettsche. “It’s not right.”

Filmmaker Korey Rowe, who spent a year traveling with Weeks, says he has no complaints about his own investment in the BitClub Network.

Korey Rowe

As speculation in cryptocurrencies has spread, more investors have also been drawn to the arcane process of Bitcoin mining — even though the chances of striking it rich in the mining business are uncertain at best, and next to none in the pyramid-scheme mining pool that BCN was offering.

The Bitcoin blockchain is often described as a form of digital ledger; every Bitcoin transaction is stored as part of a block in the chain, verified by a network of computers around the world. Miners attempt to add new entries in that ledger, a process that requires both luck and heavy-duty computing power. The miners are essentially in a contest, racing to solve daunting math problems through a vast series of trial-and-error calculations. The first miner to produce the acceptable 64-digit hexadecimal number for the next block in the chain — cracking the code, so to speak — is rewarded with bitcoin.

The odds of guessing the magic number are currently about 15 trillion to one. Your prospect of getting paid thus depends on having enough computer power to spit out many, many calculations per second, a capability that is measured in “hash rate.” Years ago, a loner might attempt to mine with a single souped-up laptop, cranking out one gigahash (a billion hashes) per second. But as competition has intensified, the need for ever-increasing computer power has encouraged miners to join together in pools, using specialized hardware and chips designed for mining, to increase their odds of producing new blocks. In response to the added firepower, the level of difficulty confronting the miners is adjusted regularly to ensure that new blocks are added to the blockchain at a constant rate — one new block roughly every ten minutes, 144 per day. At the same time, the payoff for mining keeps dwindling: While mining a block earned a 50-bitcoin reward at the outset, the reward has been halved every few years and now stands at 12.5 bitcoins. (In another few months, it will drop down to 6.25.)

Despite all these obstacles, mining deals continue to attract investors. Those who don’t want to get directly involved can enter a contractual arrangement for cloud mining, paying others to do their mining at a data center somewhere. Or they can purchase “shares” in a mining pool and hope they’re not running afoul of securities laws. Either option, it turns out, has ample opportunities for swindles.

“There’s a pattern throughout history that fraud is more likely in areas of innovation,” notes John Griffin, a professor of finance at the University of Texas whose research interests include cryptocurrency crime. “There was quite a bit of fraud in the dot-com period, too. It’s always tempting to blame the investors, but sometimes it’s difficult to ferret these out.”

Weeks (right) enjoys a little dune-buggying in an episode of "Weeks Abroad," a reality series Rowe was developing around his sense of adventure.

Korey Rowe

Beigel began sounding the alarm about BCN years before the federal grand jury indictment. He caught a spiel by one of the company’s promoters on YouTube that displayed little knowledge of mining pools and even less appreciation for the risks involved. He tried to identify the operators of BCN’s website and found the domain registrant unlisted. A statement on the site described the BCN leadership only as “a team of experts, entrepreneurs, professionals, network marketers, and programming geeks who have all come to together to launch a very simple business around a very complex industry.” No names.

Poking around online chat sites, he found other skeptics who’d uncovered bogus testimonials praising BCN. One of the satisfied customers was identified in promotional material as Victor Diaz from Brazil; the photo was that of a convicted rapist in India. Finding real people who’d made money investing in BCN was much more difficult.“If you’re promoting BitClub Network today, you’re promoting a Ponzi.”

tweet this

In 2016 Beigel posted an analysis of BCN’s investment potential, working from third-party records — which showed BCN was then responsible for 4.2 percent of the Bitcoin network’s mining activity — and from the company’s own claims about earnings. Assuming that Bitcoin prices remained relatively stable, he calculated that a BCN investor would have recovered only about 60 percent of his original investment by the time the 600-day term of the mining share had run its course.

The actual numbers were probably much bleaker. As indicated in the discussions between Goettsche and Balaci, only a small portion of the investment capital went into buying mining equipment. Two-thirds of a $600 buy-in was allocated for the membership fee, commissions and operating costs. And the investors were to be paid only half of any earnings from mining; the rest went to purchasing additional shares in the mining pool. Weeks claimed in his pitches that this forced reinvestment was like “playing with house money.”

But wait, as they say in infomercials — there’s more!

Investors might have thought that the costs of mining were coming out of the portion of their investment designated for “operating costs,” or from the half of earnings withheld for “rebuy.” BCN’s own promotional videos gave that impression. But in a 2016 Facebook exchange, one of the BCN principals explained to Weeks that this wasn’t the case. The enormous electricity cost involved in mining, a tab that consumed roughly a third of the mining revenue stream, was being paid out of investors’ earnings.

“Oh, I thought that came out of the rebuy,” Weeks wrote. “So it’s 100 percent of the mining earnings are paid out after expenses like the power bill.”

The BCN honcho — Russ Medlin, presumably, though his name is redacted in the court file — replied that the company was trying to keep that information on the down-low. “I promise you that you will cost your self time and money to focus on this,” he wrote.

In the early going, the BCN operators allegedly concealed the meager returns by cooking the books. At one point Goettsche directed Balaci to “bump up the daily mining earnings” by 60 percent, a figure that had Balaci exclaiming, “That is ponzi territori [sic] and fast cash-out ponzi.” The 2017 surge in Bitcoin prices helped, too; even tiny fractions of bitcoin in an investor’s account began to look robust in the midst of a forty-fold increase in the value of the currency. And some investors walked away happy.“We understand U.S. citizens are property, and we don’t want any trouble with your owners.”

tweet this

“I made my money back,” says filmmaker Rowe, who joined BCN while making his documentary about Weeks. “The numbers never seemed 100 percent right, but I wasn’t looking that deep into it.”

Nobody was supposed to be looking too closely at the earnings. They were supposed to be dazzled by the multi-level marketing element, the ability to earn “passive income” by getting your friends, and your friends’ friends, to join BCN, climbing their way up an unsustainable pyramid of commissions. Medlin’s online presentations crackled with MLM gibberish, promises that “every single sale through your tree counts to infinity,” and that a little bit of recruiting effort could earn you commissions of $800 a day.

The commissions were clearly a significant moneymaker for the top promoters, including Weeks, one of 104 “monster builders” in the BCN pyramid. But there was actual mining going on, too. The early claims about mining power the company didn’t have were eventually replaced with videos showcasing their hardware. Weeks claims to have brokered sales of more than $60 million in mining equipment to BCN, and he led tours of the data center in Iceland where much of the mining was taking place. (A spokesperson for Verne Global, the owner of the facility, says that the company never had a direct relationship with BCN and can’t comment on its mining capabilities.) In one video, Medlin can be seen bragging that BCN would soon be mining at a rate of 1100 petahash (more than a quintillion hashes) per second, raking in $10 million to $20 million a month in Bitcoin.

“By the end of 2018 we’ll be the number-one Bitcoin mining operation in the world,” Medlin exults.

Russ Medlin’s mug shot appears on Nevada’s sex-offender registry.

Nevada Department of Public Safety

Regardless of the sums involved, the company had another problem. The feds viewed the offering of shares in the BCN mining pool as a conspiracy to sell securities without registering them with the Securities Exchange Commission. BCN attempted to tiptoe around the regulations by having American investors contact them through encrypted networks or at online addresses that appeared to originate in other countries.

“We just change our IP addresses to ones outside USA,” Weeks explained to one potential investor in a Facebook message exchange. “All the money you make is NOT reported to the tax man so…it’s like having an offshore account growing for you tax free.”

In communications with other American investors, Weeks insisted that they were citizens of individual republics (“the Republic of Utah”) rather than the United States. He urged BCN management to put a notice on its website that would explain why the company was supposedly turning away American investors: “Despite what you may have been told, America is, unfortunately, no longer a free country. If you are a U.S. CITIZEN with a SS# (Slave Surveillance Number), then you may get in trouble with your masters at the IRS for making a bunch of bitcoin tax free…We understand U.S. CITIZENS are property and we don’t want any trouble with your owners.”

Weeks has a longstanding interest in microcountries that offer theoretical refuge from regulations and taxes. He’s visited Liberland, a disputed parcel of land on the Danube that a libertarian activist has declared to be a sovereign state, and he’s finagled an appointment as prime minister of Potinha, also known as Atlantis, an island off Portugal with a population of four. He’s joked that it would be cool to start his own country, but his fascination also reflects his growing disenchantment with his native land. “We’ve lost our way,” he told one interviewer, referring to America’s regulatory climate. “We’ve been infiltrated.”

Long before he could have been alerted to any investigation into BCN, Weeks sought citizenship in St. Kitts, where he and Goettsche had invested in a time share, then Vanuatu, an archipelago in the South Pacific that has no extradition agreement with the United States. Both applications were denied.

As the BitClub Network began to unravel, other promoters began to slink toward the exit. Stated earnings were slowing down. Angry investors were inquiring as to the whereabouts of their money. In 2019 one of the defendants, Joseph Frank Abel, publicly broke with the company. In a video showing off his own mining machines and promising “massive, massive rewards,” he issued a belated warning.

“I think BitClub is in very big trouble,” Abel said. “If you’re promoting BitClub Network today, you’re promoting a Ponzi. … They should have hundreds of millions in equipment, which they don’t. … All big lies.”

Asked at a conference if he was promoting a Ponzi scheme, Weeks replied that Social Security and the stock market were the real Ponzis.

“There’s a lot of scammers out there that are doing a lot of unethical things,” he told the Anarchapulco crowd. “Just because we’re using Bitcoin doesn’t mean we’re a bunch of criminals.”

In a video, promoters Joseph Frank Abel (left) and Russ Medlin tout BCN’s computer hardware.

YouTube

“He was trying to convince the agents that he might serve — in his words — as a ‘Jason Bourne’ of cryptocurrency,” one court pleading notes.

But the agents seemed more interested in what Weeks could tell them about the BitClub Network. A follow-up interview was arranged in West Palm Beach on December 10, 2019.

“We were talking about going to Barbados for Christmas,” filmmaker Rowe recalls. “He said he was going to be handing out shoes with Richard Branson in the rainforest to some needy children.”

Instead, Weeks was arrested at the Florida meeting. He was wearing a belt that contained thousands of dollars in cash. Questioned in custody, Weeks refused to give federal agents access to his holdings, but the investigation turned up a bank account in Dubai, a string of high-dollar international wire transfers, an empty tube in Colorado that may have once contained a cold storage (offline) bitcoin wallet, and evidence of another cryptocurrency wallet that had received transactions amounting to approximately $124 million.

There was also evidence that Weeks may have directed some BCN investors to camouflage their investments by sending them to an account controlled by him, under the name of Manna Ministries. “Say it’s a donation and nothing to do with bitcoin,” he instructed one depositor. “Put that it’s for ‘Antarctica Trip.’”“He was trying to convince the agents that he might serve as a ‘Jason Bourne’ of cryptocurrency.”

tweet this

On the same day that Weeks was arrested, federal agents knocked on the front door of Goettsche’s $1.5 million home in Lafayette. No one answered, but they saw a male figure walk across the visible area inside the house, headed for a home office. They breached the door and found Goettsche standing in the doorway of the office.

The power supply to two desktop computers had been disconnected, making it more difficult to access files on an encrypted hard drive.

The government seized his passport and more than $9 million in assets, including the equivalent of $500,000 in bitcoin in a cold storage wallet. Subsequent analysis of cold storage wallets found in Goettsche’s house indicated that transactions totaling more than $233 million had moved through his accounts — $70 million in a single two-month period. (In an online exchange between Balaci and another individual, the programmer complained that Goettsche had stiffed him on various deals. “He put me with my back at the wall because I trusted him,” Balaci groaned. “This, after I literally made him hundreds of mil in the past 2 years with his stupid projects.”)

Goettsche’s attorneys didn’t respond to a request for comment on the case. In court filings, though, they’ve contended that the wallet transactions don’t prove anything: “That funds passed at some point in time through an offline wallet, which is commonplace, says nothing at all about how those funds were used.”

Weeks’s lawyers also suggested that the vast sums passing through their client’s wallet had more to do with purchasing mining equipment for BCN than personal profit. They claim that Weeks made only $1.5 million, tops, from commissions for recruiting new members.

That doesn’t sound like much of a return for the risk involved. The charges Weeks now faces carry a possible prison sentence of 25 years. But every traveling salesman knows you have to sell yourself before you can sell anybody else — and Korey Rowe suggests that his friend Joby was a very good seller indeed.

“Joby believes in manifestation — that if you keep your mind focused on something and you stay positive, you can manifest the conclusion you want,” Rowe says. “He probably believed in Bitcoin to a fault. He chose to ignore some of the things that normal people might have seen. But I believe he didn’t know it was a fraud. He is, in my mind, a patriot who went around the world speaking the truth and trying to educate people about new technology.”

Weeks now resides in a lockup in New Jersey. Last week, after a two-day hearing, his request for release on bail was denied.

His passport has been seized. The agents who took it from him had never seen one so heavily stamped, every page full.

“He’s surprisingly positive,” Rowe says. “It’s hard to get him down, but it’s getting to him, for sure.”