- India

- International

Bumper again

Pulses farmers are set to harvest a record chana crop, but their party could be spoiled by imports.

Kalyan Hake (left) with his father at his chana field, which is almost ready for harvest. Tur procurement has started at Vikas Agro’s Takli centre. (Express photo by Partha Sarathi Biswas)

Kalyan Hake (left) with his father at his chana field, which is almost ready for harvest. Tur procurement has started at Vikas Agro’s Takli centre. (Express photo by Partha Sarathi Biswas)

“Why is the government still allowing imports? Why don’t they come and see the crop here?,” asks Kalyan Hake, pointing to the chana (chickpea) on his six acres, of which the grain on two acres has already been harvested.

As the 32-year-old farmer from Takali Bardpur in Latur taluka and district of Maharashtra’s Marathwada region prepares to harvest the remaining crop, Hake is visibly nervous about his prospective realisations. “The government’s minimum support price (MSP) for this year’s chana is Rs 4,875 per quintal, whereas it is already trading at Rs 4,200 now in Latur APMC (agricultural produce market committee) mandi. If rates are so low before even the marketing season has actually begun, imagine how much they will slide once the crop arrivals happen after Holi,” exclaims Hake, who expects his average grain yield at 8 quintals/acre this time, as against 6 quintals for the 2018-19 crop.

ALSO READ | Being one of India’s top pulses exporter, Canada urges govt to pursue consistent farm policies

The Union Agriculture Ministry, on Tuesday, estimated India’s chana production for 2019-20 at 11.22 million tonnes (mt), up from last year’s 9.94 mt and marginally short of the record 11.38 mt of 2017-18. Farmers have, moreover, planted an all-time-high 107.21 lakh hectares (lh) area under this rabi (winter-spring) pulses crop, compared to 96.19 lh in 2018-19 and 107.08 lh in 2017-18. While the acreage in Madhya Pradesh has dropped from 34.32 lh to 27.38 lh — the abundant water in reservoirs and recharged aquifers from surplus rains have prompted farmers there to sow more wheat instead of chana — it has significantly gone up in states such as Maharashtra (from 13.14 lh to 21.79 lh), Rajasthan (15.03 lh to 21.38 lh), Chhattisgarh (3.71 lh to 4.11 lh) and Gujarat (1.74 lh to 3.78 lh).

At the MSP procurement centre in Takali Bardpur run by Vikas Agro Producer Company Ltd, a farmers’ cooperative, over 5,000 pulses growers have already registered their crop for sale. “I don’t know when they will start procurement and when the payment will be made into my bank account. But there is no other place I can sell today. The APMC prices are below MSP and traders say they will fall further if imports aren’t halted. Why can’t the government just do that, rather than spending money for procurement and making us stand in lines?” points out Hake.

Tur procurement has started at Vikas Agro’s Takli centre. (Express photo by Partha Sarathi Biswas)

Tur procurement has started at Vikas Agro’s Takli centre. (Express photo by Partha Sarathi Biswas)

For farmers in the relatively dry Marathwada and Vidarbha region, chana is an ideal rabi crop to grow after their kharif soyabean, which is planted from mid-June (after the monsoon rains) and harvested by October. Cultivated mostly on the residual soil moisture, it requires hardly one round of irrigation, as opposed to three or more for wheat. This time, bountiful rains, especially during the second half of the monsoon (August-September) and extending till early November, has resulted in higher sowings and farmers like Hake even reporting a one-third jump in yields.

In Latur, a major chana-growing district of Maharashtra that also houses one of India’s biggest wholesale market for pulses, many farmers could not take their kharif crop due to poor rains in the first half of the monsoon (June-June). Hake is among those who was forced to skip his soyabean crop and, instead, went in for early sowing of chana towards the end of October. With harvesting going on at full swing, the not-so-great price outlook for the legume is a major worry.

At the Latur APMC, traders identify two main reasons for the current weak sentiment.

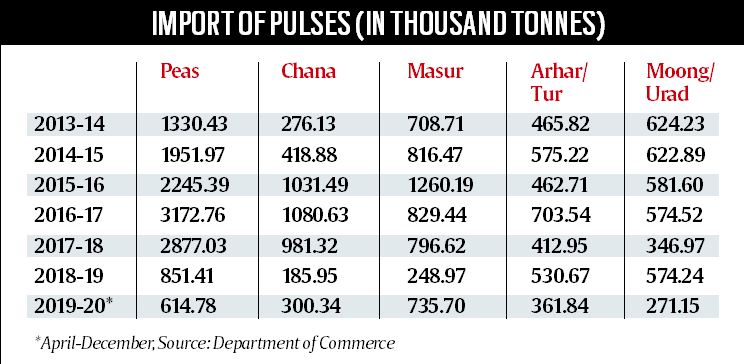

The first is imports. Since March 2018, the Narendra Modi government has clamped a 60% import duty on chana, while pegging it lower, at 40%, for the larger kabuli or garbanzo bean varieties. Earlier to that, it imposed a 50% customs duty on white/yellow peas (which are a cheap substitute for chana and even used for adulteration of besan flour made from the latter) in November 2017 and 30% on masur (lentil) in December 2017. Further, imports of tur/arhar (pigeon-pea), moong (green gram) and urad (black gram) were, in August 2017, moved from the “free” to the “restricted” list, subject to annual quantitative caps. These measures have helped stem the flow of imports from their 2016-17 and 2017-18 peaks. The current fiscal has, nevertheless, witnessed an increase, particularly of masur and chana imports (see accompanying table). Both happen to be rabi pulses crops. Masur and white/yellow peas are imported mainly from Canada, while chana is mostly supplied by Australia, tur/arhar by Myanmar, Mozambique and Tanzania, and moong and urad by Myanmar.

A second reason is the huge unsold stock of chana lying with the government from last year’s MSP-procured crop. The National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (Nafed) was, as on February 17, holding 21.03 lakh tonnes (lt) of pulses in its godowns, of which chana alone comprised 15.83 lt. According to Nitin Kalantari, a leading Latur-based dal miller and pulses trader, Nafed’s stocks alone are weighing down prices in the mandis. “They should have offloaded this grain during the Dussehra and Diwali season, when demand for besan (used in many sweet preparations) is high. Nafed is now floating tenders to sell, right at the start of the new crop’s arrivals. How can prices, then, look up?,” he notes.

At the Takali Bardpur procurement centre, Vilas Uphade, director of Vikas Agro, is having a tough time convincing all growers not to come with their crop now. The farmer producer company — part of the MAHA-FPC, a state-wide consortium of producer organisations/companies that is a sub-agent of Nafed for undertaking MSP procurement operations — began purchase of tur/arhar on February 18. “Tur (which is harvested in December-January) is also selling at Rs 4,900 per quintal (below the MSP of Rs 5,800), but our real concern is chana. Not only is the crop much bigger this year, but many farmers have not done any kharif sowing and gone directly for chana. They need a good price for what is clearly a bumper crop,” explains Uphade.

Severe water scarcity last year led Ali Mohammed Sheikh to skip his chana crop in 2018-19. The delayed onset of monsoon this time meant that he couldn’t also plant the 2019 kharif soyabean. But the monsoon’s magic revival from August enabled this 10-acre farmer from Takali Bardpur to go for chana on eight out of his 10-acre holding. “If the government procurement centres are not opened in time, I may have to settle for a price of Rs 3,500 or even lower,” sighs Sheikh, who also grows sugarcane and wheat on one acre each of his balance land that has irrigation facility.

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05