- India

- International

On hold

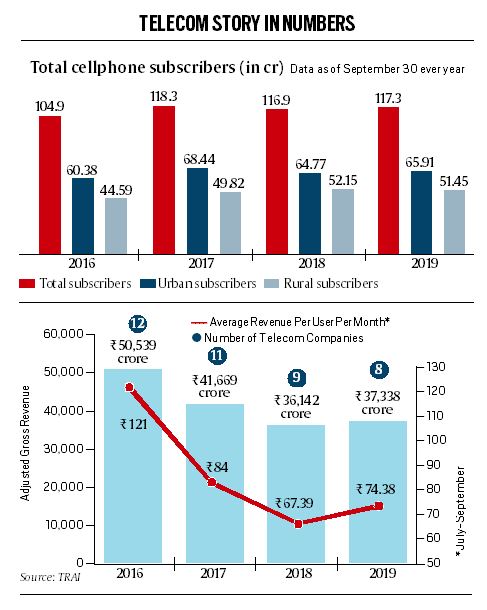

The recent Supreme Court ruling asking private telecom companies to pay Rs 1.5 lakh crore in dues is the latest blow to a sector that’s reeling under debts of Rs 8 lakh cr. The Indian Express examines the events that have ended with one of the biggest players teetering on the brink of a collapse. Can the industry, with 117.3 crore cellphone subscribers at last count, survive this crisis?

In the deeply contested space that India’s private telecom companies have been inhabiting for the last 28 years, there have been no clear winners or losers. (File)

In the deeply contested space that India’s private telecom companies have been inhabiting for the last 28 years, there have been no clear winners or losers. (File)

The story of India’s telecom sector is a bit like a football knockout tournament, where clubs lined up against each other get eliminated in every round till only the winner remains. But behind that win are often reasons beyond just good football — ranging from a club’s financial capacity to match-day conditions and decisions by match referees.

In the deeply contested space that India’s private telecom companies have been inhabiting for the last 28 years, there have been no clear winners or losers, but a combination of government policies, court verdicts, regulatory decisions, entry of competition and rapid change in technology has led to these players executing and undergoing a series of goals, tackles, saves, shots and sometimes, even a few self-goals.

The latest blow to this industry that’s struggling under a mountain of debt — more than Rs 8 lakh crore, as of date — came in the form of a Supreme Court ruling, which rejected pleas by leading telecom companies to review the court’s October 24 verdict, asking them to pay Rs 1.47 lakh crore in past licence fee and spectrum usage charges. These dues are calculated as a percentage of the telecom company’s adjusted gross revenues (AGR), that is, an operator’s total revenue minus roaming charges, service tax and access charges, among other things.

On February 14, the court came down heavily on the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) as well as telecom companies, including Airtel and Vodafone for failing to comply with its order and said the way everyone was behaving suggested there is “no law left in the country”. While Bharti Airtel is expected to pay Rs 35,500 crore, Vodafone Idea is expected to pay more than Rs 53,000 crore (though recalculation of the companies’ dues is currently underway).

Even as the companies have started making the first set of payments after the Supreme Court’s rap on the knuckles, sector analysts suggest Vodafone Idea may not have the financial headroom available to pay the full dues by March 17. This could potentially lead to a duopoly situation with only two private players — Reliance Jio and Bharti Airtel — surviving in the market. Experts have also pointed out that such a situation will prove to be disadvantageous to consumers, who could expect the two players to increase tariffs in order to make good on their investments.

So how did the telecom industry — arguably one of the biggest beneficiaries of the 1991 opening up of the country’s economy — end up here?

In the beginning was the licence fee

At the heart of all the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats the sector has witnessed is the telecom licence, its conditions and the legal interpretations of those conditions.

The current plight of the mobile services industry traces back to 1991, when the Centre started liberalising the licensing norms to allow private players to enter the sector.

In 1992, the government for the first time invited bids from companies for licences to offer cellular mobile services in the four metros of Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. Licences were awarded to eight players, two in each circle, but even before the industry could begin operations, the companies that did not get a licence moved the Supreme Court. This would go on to be the first in a series of interventions by the Supreme Court in cases that have shaped the sector. In its judgment two years later, the apex court said that it would not interfere with the government’s decision-making process unless any such decision was arbitrary in nature.

Finally, after a delay caused by the lawsuit, in 1994, the DoT came out with the first National Telecom Policy, which, among other things, targeted that “all value-added services (which include cellular mobile services) available internationally should be introduced in India… preferably by 1996”.

On July 31, 1995, the then telecom minister Sukh Ram made the first-ever mobile call in India to West Bengal Chief Minister Jyoti Basu. It was a landmark moment that was made possible by the telecom policy, but other than that, the 1994 NTP was seen as a gross overestimation of the sector’s capability to grow and invest. One of the primary constraints was the licence fee.

Chances of duopoly

An immediate fallout of the Supreme Court verdict, asking telecom companies to pay their dues, could be a cut in investment in operational infrastructure, which could affect quality of services for consumers. It could result in further consolidation of the sector, effectively leaving only two players in the fray.

In 1994, the fixed licence fee arrangement of the DoT was set circle-wise — Rs 3 crore for Mumbai, Rs 2 crore for Delhi, Rs 1.5 crore for Kolkata and Rs 1 crore for Chennai. The fee was revised every year, and by 1999, it had become Rs 24 crore for Mumbai, Rs 16 crore for Delhi, Rs 12 crore for Kolkata and

Rs 8 crore for Chennai. However, after having doled out more than 30 licences, by 1998, the government saw eight operators default on their licence fee payments.

The first round of elimination took place.

A different model

The exit of these operators got the government to take a hard look at the situation and it asked the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) to conduct a study on the financial stress in the sector. In its report, the regulator highlighted the high licence fee as one of the pressure points on the telecom companies.

The TRAI report led to the NDA government in 1999 to come out with a new telecom policy that envisaged a move from fixed licence fee model to a revenue-sharing model, where companies paid a certain percentage of their AGR as licence and spectrum fee. Besides, TRAI also regulated telecom tariffs, thus pushing the growth of cellular services for the first time.

Shortly thereafter, in 2001, the government issued licences for basic telephone services that used WLL, or wireless in local loop, technology that enabled landline operators at that time, such as Tata and Reliance, to offer wireless services. This was also the first time licences were issued on a first-come-first-serve basis — a policy, which had consequences that later led to a complete upheaval of the sector.

The telecom sector’s golden period had just begun. The number of cellular subscriptions per 100 people ballooned from less than one to nearly 70 over the next 10 years. A number of foreign players bought licences. The incumbents also saw revenues rise multi-fold. The intense competition in the sector saw regulatory interventions such as the introduction of an interconnect usage charge that effectively allowed operators to do away with the incoming call charges.

In 2003, DoT raised the first AGR-related demand, saying all revenue earned by telcos from dividend from subsidiaries, interest on short-term investments, money deducted as trader discounts, discount for calls, etc. —essentially, activities beyond the domain for which they obtained the licence — would be included in their AGR. Such a calculation effectively increased the levies that the telecom players had to pay.

The operators, under a unified front, approached the Telecom Disputes Settlement Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT), which in July 2006 ruled that the matter must be sent back to TRAI for fresh consultations. TDSAT rejected the government’s contention and the Centre moved the Supreme Court.

The period also saw the entry of Vodafone Group into India in 2007 with its acquisition of Hutchinson Essar for $11 billion, giving the company access to nearly 22 million subscribers. The bet was mainly on the immense potential that the Indian telecom sector was seen to be having at the time, for which Vodafone paid about $500 for every subscriber it acquired. Various companies were also experimenting with different strategies, offering novel products to consumers such as the per-second billing plans, Rs-10 recharge packages, etc.

But this honeymoon lasted only till 2012, when the Supreme Court cancelled 122 telecom licences in the now infamous 2G scam case. The cancellation of licences by the Supreme Court prompted the key stakeholders — government and telecom operators — to revamp the sector, with spectrum now being allocated through auctions.

The verdict also forced many corporates, especially foreign players, to cut back on their India exposure. It thus impacted bank books, with loans to telecom companies and infrastructure providers comprising nearly 3 per cent of the portfolios for lenders at that time. The companies that saw their licences being cancelled included those with investments from foreign players such as Telenor, Etisalat, Sistema, Bahrain Telecommunications, Malaysia’s Maxis, etc.

The second round of elimination took place.

Enter Jio

For the survivors of the 2012 judgment, including players such as Bharti Airtel, Vodafone India, Aditya Birla Group company Idea Cellular, Reliance Communications, Tata Teleservices, Telenor India, Videocon Telecom, Aircel, etc., growth continued, albeit in a way that significantly leveraged their books. Though the proliferation of mobile services continued to happen, the process of acquiring costly spectrum partly contributed to the financial stress in the sector.

Another period of growth continued till 2016, during which a voice-heavy telecom industry saw an uptick in tariffs, backed by TRAI’s move to not interfere in tariff setting.

In September 2016, Reliance Industries Ltd announced the launch of Jio with an introductory offer of free voice and data services that rattled the incumbents. Just months before the nationwide commercial launch of Jio, a wave of consolidations and exits hit the sector. While bigger players started to combine their firepower, the smaller ones began to jump ship.

The data wars began and led to two of the three biggest companies in the country — Vodafone India and Idea Cellular — joining hands. All this happened even as operators continued to underestimate 4G and overestimate the survivability of legacy services such as 2G and 3G.

“No one had imagined that a company with such deep pockets would come in at such a large scale and start offering free services. Even from a regulatory and policy perspective, we were caught off-guard,” said a senior TRAI official.

Jio officials underlined the high efficiency of 4G that brought down costs. However, incumbent operators heavily criticised TRAI’s move to reduce interconnection usage charge from 14 paise a minute to 6 paise per minute. This is the fee that the operator, from whose network a call is made, pays to another operator, to whose network a call is made.

Mails seeking comments from Bharti Airtel, Vodafone Idea and Reliance Jio did not elicit a response. Queries sent to TRAI also went unanswered.

The consolidation led by the so-called data wars pushed even more companies out of the sector. Post the Vodafone-Idea merger, only three private players remained in the Indian mobile services market.

The third round of elimination took place.

What next?

With its back pushed to the wall, Vodafone Idea’s top leadership has been talking about the inability of the company to continue as a going concern, causing a panic situation among the operator’s subscriber base.

For the fiscally strained government, the Supreme Court ruling on AGR dues of telecom companies has created a Catch-22 situation. While on the one hand, it has a strategic sector to protect, on the other hand, the government has to manage a fiscal deficit situation while also complying with the Supreme Court’s orders.

In a recent note, Bank of America Securities postulated certain scenarios going ahead. “We believe the market could be surprised if Birla or Vodafone group inject equity in Vodafone Idea. Both parent companies have consistently maintained the view that they are unlikely to inject more cash for the next 18-24 months; if the government potentially takes an ordinance route in Parliament and decides not to charge penalty/interest from telcos; if there is any asymmetric regulation favouring Vodafone Idea given its balance sheet is more stretched and needs relief. We see low possibility of these events,” it noted.

From a consumer perspective, a duopoly would not only mean costlier telecom services but also constrained incentives for operators to maintain quality of services.

In December 2019, even with three players in the market, all of them almost simultaneously announced increased tariffs in the range of 15-40 per cent. Now, one player less would mean that the survivors could have greater pricing power — a factor that makes their stocks more attractive, according to those tracking the sector.

The quality of services is also a matter of concern, with the sector coming under fire from both by the government and the TRAI over the last few years for the call drop situation. However, beyond minor penalties, neither the Centre nor the regulator have the necessary legal teeth to compel operators to improve services.

TRAI, in 2016, had come out with regulations imposing mandatory compensation by telecom operators to subscribers for call drops. But later that year, the Supreme Court struck down TRAI’s order, calling it “arbitrary, ultra vires, unreasonable and not transparent”.

Experts suggest any move to save or bail out the telecom sector will require strong political willpower on behalf of the government and policymakers, considering it will need to find a fine balance between the health of the sector, consumer interest and its own fiscal headroom.

Apr 18: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05