When Nidia Becerra first vowed to drive out illegal mining and logging from her indigenous community’s ancestral lands in Colombia, her elders and traditional spiritual guides, known as “Sinchis Yachas,” warned there would be trouble.

“I would have to proceed with a lot of caution, or I would be dead,” she remembers them telling her.

Almost 10 years later, Becerra still takes that advice to heart. She sometimes wears a bulletproof vest when out in public and frequently changes her residence. When she travels, she’s often accompanied by armed guards provided by the government or the indigenous communities she’s fighting for.

Colombia is the most dangerous place in the world for activists who seek to help protect land and other natural resources, according to a recently released report by Front Line Defenders, an Irish advocacy group. And the trend is getting worse. More than 40 human rights defenders and community leaders have been killed in Colombia since January, including a national park ranger and several indigenous rights and environmental advocates, according to Indepaz, a Colombian peace-building nonprofit based in Bogotá.

Becerra, 31, has dedicated her life to helping indigenous communities throughout Colombia protect their territories by obtaining legal recognition of their lands by the government and stopping mega-infrastructure projects like roadways and hydroelectric power plants from being built in these regions without the communities’ consent, all while risking her life.

She is one of three activists who spoke with NBC News to detail what they say is a constant threat of violence that accompanies their work.

Over the years, Becerra said she has received hundreds of calls and texts and has had flyers left at her doorstep calling for her death. In 2014, armed men shot at her. But she says nothing can stop her from continuing her work.

“Each time an attempt is made against my life, I come back stronger, and this is just further proof that I need to continue in this fight and struggle,” she said.

Colombia is not the only part of the world where violence is routinely used to silence nature-focused reformers and organizers.

Protecting the environment and indigenous land rights is becoming an increasingly fatal mission for activists worldwide. Just in the last month, two monarch butterfly conservationists were killed in Mexico, and a group of armed men killed six indigenous people on a nature reserve in Nicaragua.

According to Front Line Defenders, more than 300 human rights leaders were killed last year in 31 countries, and nearly half of those killed were targeted specifically because of their environmental activism. The Philippines, Honduras, Mexico and Brazil all ranked among the deadliest of countries after Colombia, where the slayings of 106 human rights activists were documented in 2019.

Climate activism in Colombia often takes the form of advocating for indigenous people and their lands, which Becerra says are intrinsically connected.

“The connection is so profound between humans and nature and land that a violent act against land, or vice versa against woman or man, is a violent act against the other,” she said.

This belief system is what drives Becerra and many other indigneous activists to defend the environment at all costs. Because of this protection, indigenous peoples are oftentimes living on some of the earth’s most well-preserved lands, says Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples. But these lands are highly coveted by powerful economic interests eager to mine gold, harvest timber or extract oil, she said.

“We’re essentially coming down to a question of profit,” said Ed O’Donovan, one of the lead authors of the report, who is also responsible for overseeing Front Line Defenders’ work to help support and protect human rights leaders at risk around the world.

As legal and illegal entities force themselves upon the lands of indigenous peoples to exploit their natural resources without their consent, many of these communities are displaced due to violence or have their traditional livelihoods eradicated as local forests are wiped out and water sources are contaminated.

When the communities resist, they often find themselves in the firing line of criminal interests associated with these groups, said Ben Leather, a campaigner for Global Witness, another organization that has been tracking the violence against environmental defenders around the world since 2002.

“They’re stepping on big toes, and on the toes of big interests,” he said.

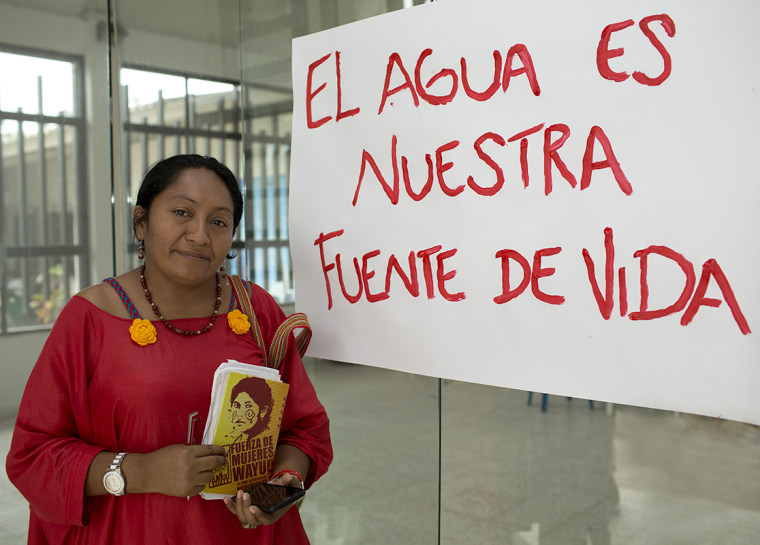

Jakeline Romero, an indigenous rights activist, has experienced this first hand in her own Wayúu community in La Guajira, Colombia. For years, she’s protested the Cerrejón coal mine that she claims turned the local water source black with chemicals until it eventually dried up completely, forcing her people and other local Afro-descendant communities to move away from lands they had lived off for generations, herding livestock and growing their own food.

Romero said she has received countless death threats over the years for protesting such mining operations and seeking reparations for the damages done, as have numerous other women she works with.

“They threaten you with rape, or with the killing of your son or your mother,” she said.

Activists in Colombia often face a convergence of many powerful interests. In addition to mining operations, communities often face major infrastructure projects from national and multinational companies as well as paramilitary groups and drug cartels vying for control of the country’s most resource-rich territories to grow and transport illicit drug crops.

Activists have also faced a growing threat as political shifts in Colombia have opened the door for new conflicts.

Many of the areas at stake were previously controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia People's Army, more commonly known as FARC. These lands historically or legally belonged to indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups, including Afro-descendant communities, who were displaced during the 50-year civil war between the FARC and the Colombian government.

When the conflict officially ended with the signing of the 2016 peace accord, these communities began returning to reclaim their ancestral lands, only to find themselves in the middle of another war they say they have been left to fight on their own.

In May, Afro-Colombian activist Clemencia Carabali was attending a meeting with other prominent Afro-Colombian leaders when a group of armed men opened fire and threw a grenade at them. No one was killed, but according to the Washington Office on Latin America, a research and advocacy organization, several people who were at the meeting received a text stating “what happened on Saturday was only the beginning of the extermination of it all.”

These types of attacks are “destabilizing,” said Carabali, who has been a human rights and environmental defender for more than 20 years.

But she said she will not let violence deter her.

“That’s exactly what they want,” Carabali said. “That we leave the territory so that they can continue taking away what is left.”

The Colombian government has claimed that it is committed to protecting human rights leaders by assigning them personal protection units and pursuing investigations.

“We reiterate that all the unfortunate cases of homicides, threats and other aggressions against human rights defenders and social leaders are being investigated by the Attorney General's Office, with support from the Elite Corps of the National Police, obtaining important results in order to prevent these acts from remaining in impunity,” wrote a representative from President Iván Duque’s Council on Human Rights and International Affairs in a recent statement sent in Spanish.

The statement said that the attorney general's office said specifically that of the 370 assassinations of human rights defenders since 2016, their office had made advances on the investigations of about 52 percent of the cases.

Activists and researchers who spoke with NBC News said they do not have faith in the government’s efforts to stop the violence.

“I don’t have high expectations for the protection that the government offers,” said Becerra, who is the Amazon regional coordinator for the indigenous rights group Land Is Life.

In December, she filed a complaint with the attorney general’s office detailing the dozens of death threats she has received. So far, she says no progress has been made to identify the perpetrators and hold them accountable.

It is not only up to the Colombian government to protect its country’s human rights and environmental defenders, said Leather from Global Witness. International companies doing business in Colombia must ensure that their operations are not displacing people or contributing to any other form of violence against those protecting the planet’s natural resources, he said.

“If we’re really serious about stopping climate change, we should be supporting the people on the forefronts of that movement who are these indigenous peoples who’ve shown how to live sustainably for centuries.”