‘You’ll have to excuse me, I’m just trying to fight with this veil,” says Viviana Durante, wrestling with an unwieldy sheet of coral silk as I walk into her studio. Voluminous wafting scarves are a key prop in the image and mythology of Isadora Duncan, the American pioneer of modern dance whose life was as free-spirited as her art. Durante is hoping to tap into some of that spirit in her latest production, honouring the unconventional dance icon.

A leading ballerina with the Royal Ballet in the 1990s, 52-year-old Durante is returning to the stage in Isadora Now, the third outing for her own company. As well as Durante performing Frederick Ashton’s Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan, there will be the rare sight of a 1911 Duncan work, Dance of the Furies, and a new piece by Joy Alpuerto Ritter, recasting Duncan’s freedom of expression and feminist power for current times.

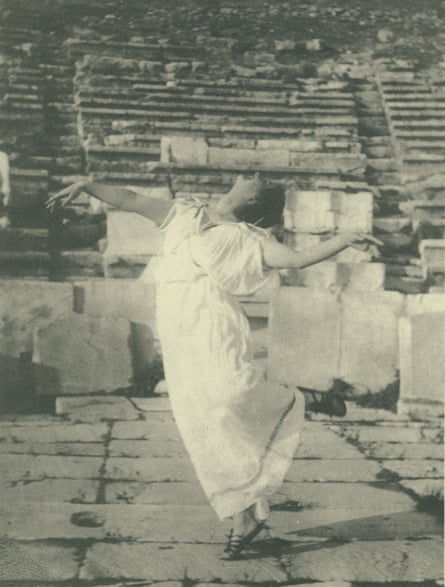

Duncan’s flowing, full-bodied dance was a rejection of the restrictions of classical ballet, inspired by her love of ancient Greece and performed in the drawing rooms of the wealthy in London and Paris at the turn of the 20th century. She expressed spirituality and sensuality, and garnered ardent fans – Rodin called her “the greatest woman the world has ever known” – as well as critics.

“She was very radical and very shocking,” says Durante. “She had no inhibitions about showing or saying what she felt through her dance. And she wasn’t afraid of the darkness of life.” Duncan’s own life held tragedy – the deaths of her children, two by drowning and a third soon after birth, then Duncan’s own death in a freak accident aged 50 when her scarf got caught in the wheels of an open-top car.

But Duncan’s influence lives on, and in the studio her expressive abandon, grounded to the earth in bare feet, is proving tricky for Durante’s petite, classically trained physique. Durante was always a passionate dancer, but within the refined context of ballet. “I’m trying but my feet are still in pointe shoes,” she says, metaphorically. “It’s not in my body yet!”

At her peak, Durante was one of the best in the world, and to any casual observer her dancing still looks exquisite, but in the studio she gives a commentary of criticisms and apologies, tough self-judgment being an ingrained part of any ballet dancer’s makeup. Yet when we meet again a few months later in her dressing room at the Barbican, some of Duncan’s essence has seeped in. “I wish I’d experienced this process back when I was dancing [at the Royal Ballet],” she says. “You’re not just learning the steps, it’s much more like a spiritual journey that she takes you on.” Immersing herself in Duncan’s story has been a revelation for Durante. “She’s taught me to love my skin, my body, who I am,” she says. “She celebrated women. She’s taught me to celebrate myself more. As a dancer you do tend to doubt yourself, especially a classical dancer.”

Ballet training doesn’t teach you to love your own skin? “Absolutely not,” she says. “And it’s a shame – dancers should learn to love themselves more, because it opens your mind.”

Last year, Durante was appointed director of dance at English National Ballet School. “I tell the students all the time, ‘I want you to have a voice.’ If you’re trying to teach somebody to have responsibilities on stage with their role, they also have to take responsibility for themselves. You have to allow them to grow, not just as a dancer but as people: the person is the dancer, and the dancer is the person. And as you grow older it’s fine to appreciate that and not remain this childlike [dancer] – I think there’s a danger of that.”

Durante’s own career was derailed when she raised her voice, back in 1999, over a concern about the partner she’d been assigned, which led to the management cancelling her appearances and her leaving the Royal Ballet. “I think dancers have more of a voice now,” she says. “But there’s a tendency for a dancer to always think they’re wrong, they’re saying the wrong thing, which does not help them reflect on how they dance.”

Durante’s company comprises six dancers from classical and contemporary backgrounds (including ex-ENB principal Begoña Cao) and she is encouraging them to trust themselves and embrace their femininity in all its forms. Duncan herself said she wanted not to dance in ballet tropes of nymphs and fairies, but “in the form of woman in its greatest and purest expression”. “And that’s why I celebrate Isadora,” she says. “She was a very courageous woman who celebrated herself – and celebrated dance.”

Viviana Durante Company: Isadora Now is at the Barbican, London, 21-29 February.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion