Donald Trump is not known for downplaying foreign threats. And yet, as the Wuhan coronavirus triggered quarantines throughout China, moved into South Korea, Italy, the United States, and at least 36 other countries — while throttling global supply chains and depressing foreign markets — the fearmonger-in-chief remained sanguine. At the World Economic Forum in late January, Trump assured the gathered plutocrats that the virus was “under control.” Three weeks, hundreds of deaths, and one giant stock market plunge later, the president’s song remained the same.

“The Coronavirus is very much under control in the USA,” Trump tweeted Monday. “We are in contact with everyone and all relevant countries. CDC & World Health have been working hard and very smart. Stock Market starting to look very good to me!”

The source of Trump’s uncharacteristic reluctance to talk up a border-crossing menace to American public safety isn’t hard to discern. As several news outlets have reported over the past 48 hours, the president fears that panic over the looming pandemic could chill America’s hot economy — and nullify his strongest reelection argument in the process.

A pandemic is nothing if not a reminder of our species’ limited capacity to anticipate the future. If a microscopic organism spreading from a bat to a human body can bring the global economy to the brink of crisis, then who knows what other unknown unknowns are waiting to surface between now and November 3. To accept that we are all hurtling ever deeper into a moonless night, our train jostling and switching tracks in response to forces we can’t comprehend, let alone foresee, would be to surrender to a nihilistic fatalism (and, more critically, put horse-race pundits out of business).

So while no one can tell you where the COVID-19 outbreak is headed — or whether Trump’s fears about its political implications will prove prescient — here are five ways the virus could potentially impact the 2020 election:

1) The pandemic could sicken the economy, thereby sending the Trump presidency to an early grave.

The White House has good reason for sweating this scenario. Although the president commands the worshipful affections of the GOP faithful, he has little personal appeal to those beyond the Church of Donald Trump and the Latter-Day Schlemiels. The reason he has managed to keep his approval rating in the mid-to-high 40s — and his odds for reelection north of 50 percent — is that he has presided over a steadily improving economy for nearly the entirety of his first term. For months, America’s unemployment rate has been hovering near half-century lows. Wages have been rising (slowly but surely) even at the bottom of the labor market. Consumer confidence is hitting post-recession highs, Americans are expressing “record-high optimism” about their own personal finances (59 percent say they are better off now than last year, while 74 percent expect to be better off next year than they are now), and 55 percent of Americans approve of Trump’s stewardship of the economy.

All this has enabled a small but significant segment of swing voters to look past their antipathy for Trump’s tweets and deportment. The public’s esteem for the president’s economic management has always oustripped its approval for the man himself. But as the labor market has grown ever-tighter, Trump’s job approval rating has ticked up toward all-time highs. If his favorability rating remains frozen in place, while the economy continues on his current trajectory, most fundamentals-based election models would project his reelection.

By the same token, given his exceptional personal unpopularity, a reversal of economic fortune would be liable to bruise Trump even worse than it would a typical incumbent. And there’s reason to fear a global recession could be one symptom of a coronavirus pandemic (as recent market developments have indicated).

Some early analyses of the economic threat posed by COVID-19 found comfort in the precedents set by the 2003 SARS outbreak (which was itself a different form of coronavirus). In that instance, U.S. financial markets weathered the six-month outbreak, and then rode a spike of catch-up growth after the epidemic abated. But the SARS precedent is an unreliable guide for the present crisis in multiple respects. Beyond the fact that this coronavirus is much more contagious than its predecessor, China is far more central to the global economy than it was 17 years ago. The nation’s share of global trade has swelled from 5.3 percent in 2003 to 12.8 percent last year. It is now the world’s manufacturing mecca, and a central node in myriad global supply chains. Meanwhile, thanks to its income gains over the past two decades, China is no longer merely a supplier to American firms, but also a key consumer market.

And it was already battling slowing growth and mounting debt loads before an epidemic forced it to lockdown entire cities, constraining the consumption of hundreds of millions of people, and pushing countless small businesses to the brink of bankruptcy. Even if the virus had been contained within the country, its resultant disruptions would have been sufficient to dampen the outlook for global growth by a modest but significant degree.

And the virus has not been contained. In fact, coronavirus cases are spiking in Iran, South Korea, and Italy, where it has incapacitated the commercial center of Milan.

COVID-19 isn’t exceptionally lethal, but, for that very reason, it is exceptionally contagious. Ordinary influenza viruses kill about 0.1 percent of those infected. The H5N1 avian flu virus had a fatality rate around 60 percent. COVID-19, by contrast, appears to kill a bit less than 2 percent of those who contract it. This makes a coronavirus diagnosis less harrowing for the individual, but it also makes the bug’s emergence a more profound threat to global public health than many more fatal ailments. The severely ill don’t travel much; the dead shake few hands. But the median victim of coronavirus may not know that they are sick at all for the first few days the virus is incubating inside them. And at least some reports suggest individuals can spread the disease even before they are symptomatic. Regardless, many who do present with symptoms will be unable to distinguish the disease from the common cold. In other words, the virus is nonlethal enough to spread widely, but sufficiently deadly to be experienced as a public health crisis and mass killer of the elderly or already infirm.

China’s heavy-handed quarantine measures appear to have been somewhat effective. New cases in the country are declining. But it’s not clear whether this trend will survive the resumption of business as usual, which the Chinese authorities are understandably anxious to commence. Meanwhile, COVID-19’s arrival in Milan — a financial hub and tourist haven frequented by border-hopping E.U. elites — threatens to hasten the its ascent to the status of an official global pandemic.

Ryan Avent, a columnist for The Economist, outlines the potential economic fallout of this increasingly likely scenario:

Beijing is understandably eager to get things up and running again. But now there are serious outbreaks elsewhere in the world. Operating the economy at anything like its normal level therefore opens China to the very real possibility of infections flowing back into the country, and triggering a whole new phase of the epidemic. And even if China were to completely ignore that threat, getting back to 100% operation would be very difficult given the outbreak-related interruptions now coming to other large economies and Chinese trading partners. It is hard to picture a scenario in which China does not continue to operate well below its capacity for at least another month: and you can add to that every day the global spread gets worse rather than better.

Of course, as costly as an idled China is, the rest of the world features in the picture now. And honestly, we have very little idea how this is likely to play out. In terms of the nature of what we’re facing, well, it’s a supply shock: a reduction in the capacity of the economy to produce goods and services, as opposed to a drop in people’s willingness to spend. Shuttered factories, canceled events: those all represent obstacles to the creation of GDP. When you say supply shock, those who think of anything tend to think of the 1970s and the aftereffects of the oil crises. But as I explain in my most recent column, many—and perhaps most—supply shocks don’t look like that. They are more likely to feature shattered confidence, tumbling stock prices and deflationary pressures…The world has never experienced a supply shock with this disruptive potential in the era of hyperglobalization.

Avent’s most alarming observation may be this: The past decades of demand-induced slumps have conditioned us to expect we can stimulate our way out of hard economic times. The market’s initial nonplussed reaction to the burgeoning epidemic earlier this month was at least partly predicated on a faith in the Federal Reserve’s capacity to turn economic tides through new waves of easy money. But no central bank can print stable supply chains, or hospital beds, or healthy, fearless workers.

Thus, it is not difficult then to see how COVID-19 could make the Trump campaign into one of its most famous victims. Especially since:

2) The pandemic could throw a spotlight on the Trump administration’s criminal negligence.

Thanks to the economic tailwinds he inherited (and the marginalization of Puerto Rico in American public life), Donald Trump has paid little political price for his slothful ignorance or commitment to purging the executive branch of all experts save for those who specialize in sycophancy.

But the coronavirus could change that. In fact, a COVID-19 pandemic seems almost tailor-made to expose the abject irresponsibility of the sitting president, and rendering his negligence politically salient.

Since taking office, Trump has:

• Tried to slash national health spending by $15 billion.

• Cut the disease-fighting budgets of DHS, NSC, HHS, and CDC — paring back the global health section of the latter so profoundly, it went from operating in 49 nations to just 10.

• Allowed the ranks of the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps to steadily erode (after trying and failing to shrink its budget by 40 percent).

• Eliminated the federal government’s $30 million Complex Crises Fund.

• Shut down the National Security Council’s entire global health security unit.

But what the Trump administration has lacked in general health-crisis preparedness, it has absolutely not made up for in acute crisis management. As already mentioned, since the onset of the outbreak, the president has baselessly assured the public that the virus was contained, undermining his administration’s ability to credibly counter potential conspiracy theories or misinformation about the public health crisis. Meanwhile, the administration overruled CDC scientists (and the president’s unknown preference) by evacuating 14 Americans on a cruise ship plagued by coronavirus — and then bringing them back to the U.S. aboard a plane filled with other noninfected Americans, who therefore spent hours sharing recycled air with the contagious.

The administration’s ineptide appears to be deepening in tandem with the crisis. On Tuesday, the CDC’s immunization chief warned Americans that the coming “disruption to everyday life may be severe,” even as National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow assured the public that the virus had been “contained” — or at least, containment efforts had been “pretty close to airtight.”

Meanwhile, in testimony before the Senate, Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf revealed that he (ostensibly) knows less about the Wuhan coronavirus than anyone who has read two articles about it.

All of which is to say, COVID-19 may well depreciate the president’s primary political asset (the strength of the U.S. economy) while drastically increasing the salience of his chief electoral liability (the fact that he is comprehensively unfit to faithfully execute the responsibilities of his office).

3) Alternatively, the virus just might deliver Trump a perfectly timed economic boost that all but guarantees his reelection.

This scenario looks less likely today than it did two weeks ago. But it remains possible that a combination of public health efforts, warmer weather, and the end of the school year (children’s classrooms being exceptionally conducive to the spread of illness) will kill off the pandemic by mid-summer. In which case, if the foundations of global growth remain intact (a big if, to be sure), the pandemic could ultimately redound to Trump’s benefit by yielding a surge of comeback growth, just as voters head to the polls.

As Axios reported in early February:

S&P Global expects the outbreak to “stabilize globally in April 2020, with virtually no new transmissions in May.” And most economists predict the world will get back to business as usual by the summer — and make up for lost time with accelerated economic growth in the second half of the year.

“We’re likely to return not just to normal but above normal because of the U.S.-China trade deal,” Kristina Hooper, chief global market strategist at Invesco, tells Axios. “We got this really nice boost of sentiment coming from that phase one deal, and literally within a few days of that, global media started reporting on coronavirus … Once contagion is under control and stabilized, I think we’ll see a pop in consumer spending and corporate spending.”

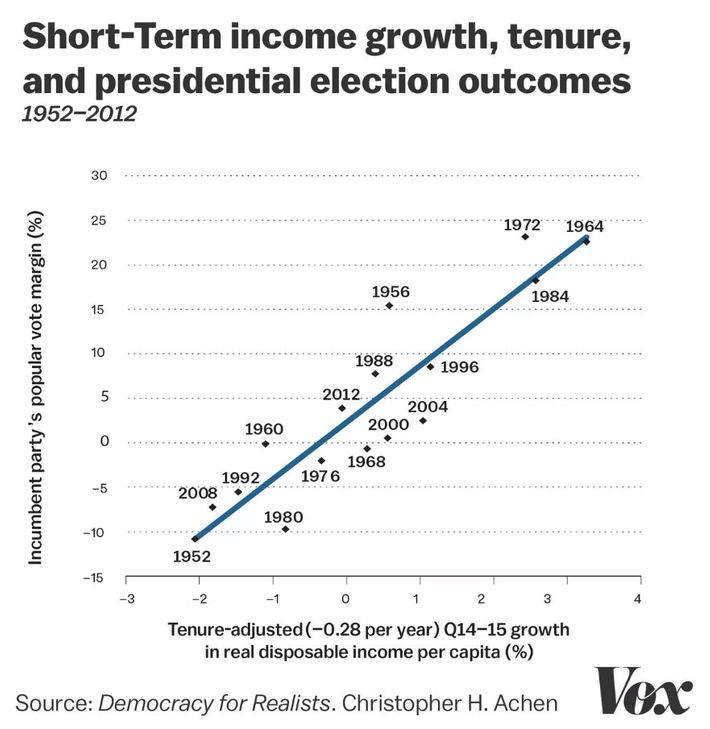

As the political scientists Larry Bartels and Christopher Achen have documented, voters do reward incumbents who preside over strong economic conditions in the months immediately before an election.

4) The pandemic could lend credence to Trump’s anti-globalist worldview.

As the Council on Foreign Relations warns:

[G]lobalism, embraced by China but rejected by the Donald J. Trump administration, is likely to be the biggest victim of the pandemic. A highly connected global economy not only facilitates the spread of the coronavirus, but also exacerbates the negative economic impact. Open economies and economies with a prominent service sector (e.g., tourism) are particularly vulnerable to economic shocks associated with a pandemic. The economic losses, in turn, will strengthen forces of protectionism and isolationism. As a result of the shortened supply chain, production worldwide may become more localized or regionalized.

Of course, Trump’s anti-globalism has never been exclusively (or even primarily) economic in nature. And early signs suggest that a coronavirus-stricken America will be a breeding ground for the paranoid xenophobia that is Trumpism’s lifeblood.

5) When socialism comes to America, it may be wrapped in a respirator mask and carrying tissues.

And yet, if a global pandemic threatens to validate Trump’s exclusionary nationalism, it could also alert Americans to our collective interest in socialized medicine and paid sick leave. After all, in the context of an epidemic, the inability of any one U.S. resident to access health care — or take off from work when ill — doesn’t just imperil that individual; it undermines the health and safety of anyone in his or her proximity.

This Miami Herald story on the plight of an exceptionally socially conscious young Miamian’s response to the coronavirus outbreak throws this point into sharp relief:

After returning to Miami last month from a work trip in China, Osmel Martinez Azcue found himself in a frightening position: he was developing flu-like symptoms, just as coronavirus was ravaging the country he had visited.

Under normal circumstances, Azcue said he would have gone to CVS for over-the-counter medicine and fought the flu on his own, but this time was different. As health officials stressed preparedness and vigilance for the respiratory illness, Azcue felt it was his responsibility to his family and his community to get tested for novel coronavirus, known as COVID-19.

… He had the flu, not the deadly virus that has infected tens of thousands of people, mostly in China, and killed at least 2,239 as of Friday’s update by the World Health Organization. But two weeks later, Azcue got unwelcome news in the form of a notice from his insurance company about a claim for $3,270.

A health-care system (and/or political economy) that imposes draconian punishments on people who take socially responsible measures in response to a viral outbreak seems liable to lose legitimacy in the midst of a pandemic — especially if the Democratic nominee happens to be the standard-bearer of a movement for transforming the U.S. health-care system.

This litany is far from comprehensive. Most conspicuously, it gives little consideration to the severe logistical disruptions that a pandemic could introduce to the 2020 campaign. (Will the CDC forbid party conventions? Will canvassing become tantamount to low-grade bioterrorism?) Such contingencies are fascinating to contemplate, but their electoral implications seem too opaque to merit speculation.

But whatever the fates have in store for our respiratory systems or republic, we retain some agency over the crisis’s political implications. We can implore our fellow citizens to see the pandemic as a testament to humanity’s inescapable interdependence (rather than the inevitability of closed borders), the necessity of universal health care (rather than family food buckets), and the hazards of placing power in the hands of nihilists who traffic in conspiracies and alternative facts (rather than placing power in the hands of the administrative state’s scientists and impartial experts). And if our efforts fail to prevent coronavirus from poisoning our old and enfeebled body politic, at least American democracy will have died trying.