- India

- International

How a Bhopal-based publisher is changing the rules of children’s literature in Hindi

Ektara, founded by Hindi poet and editor Sushil Shukla and Shashi Sablok, publishes Hindi books, creates posters and brings out two magazines for children, Pluto and Cycle, treats kids as equals and speaks to them about almost everything — poetry and nature, art and atheism, science and sexuality

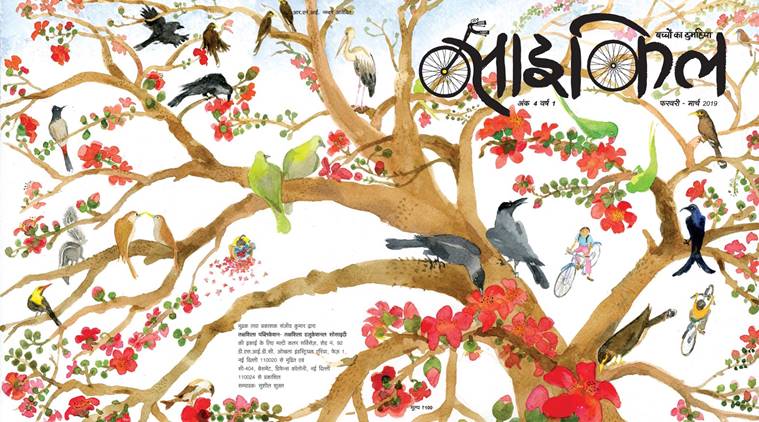

Cycle (Source: Ektara)

Cycle (Source: Ektara)

Children live in the same world as us. Amid plants, rivers and humans around us. Then why is their literature so different from ours? Why is the language we read so full of pleasure and meaning, but for children, we are still writing that same poem: baarish aayi, baarish aayi? Why can’t a children’s poem say: Jiske paas chali gayi meri zameen, uske paas mere barishey bhi chali gayi (The one who has taken my land, he took away my rains, too)?”

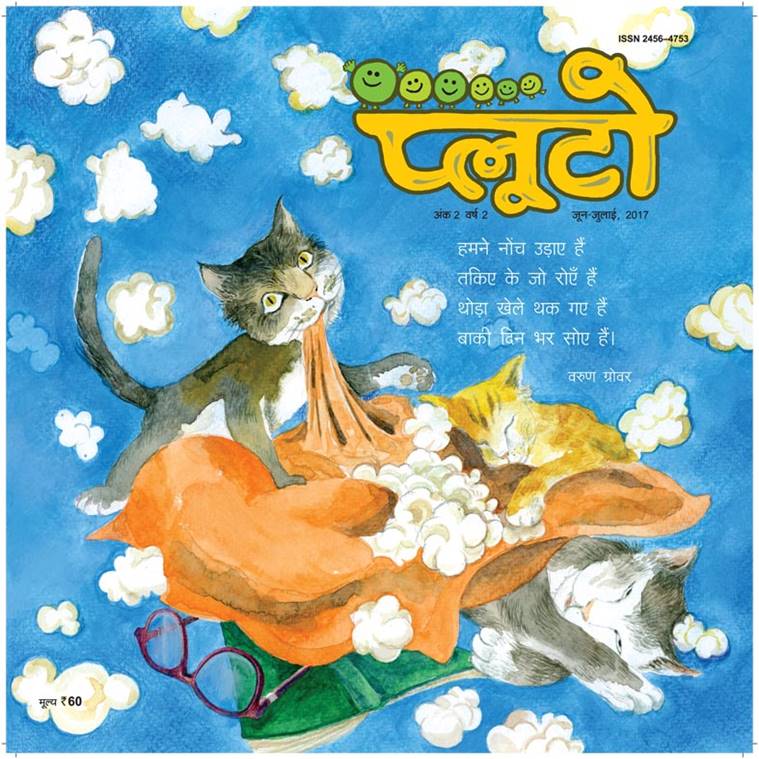

For Sushil Shukla, these are old questions, with which he has been wrestling for at least a decade – as a poet and editor. The answers are to be found in the work of Ektara, a centre for children’s literature and art in Bhopal that he runs with Shashi Sablok, the Hindi books they publish, the posters they create and the two bi-monthly Hindi magazines for children that they bring out – Pluto (for children up to 9 years) and Cycle (9-16 years). “We think that we can speak to children about almost anything. Bachche nahi samjhenge – that idea we leave outside,” says Sablok, 52.

Pluto

Pluto

What is also shown the door is the itch to instruct children on life; what is invited inside is poetry, art and open-endedness. From atheism to nature, science and sexuality, Cycle talks to the reader about an impressive range of themes. A random browsing of Cycle’s back issues from 2019 throws up gems: a serialised comic on Prashant bhaiyya, a boy who loves to wear saris and dance in school plays. A spread of haikus on aks – reflections of animals and birds in rivers and streams – by poet Teju Grover is laid out with exquisite, shimmering watercolours. A centrespread depicts the riotous north Indian baraat, lit up by men carrying large chandeliers, with the caption: Shaadi mein ujaale uthane wale apne hi ujaale tale dabe rehte hai (Men carrying the lights, burdened by the light). The magazine artwork is striking, as Ektara pools together the talent of some of India’s best illustrators, from Proiti Roy, Priya Kurian, Tapashi Ghoshal to Atanu Roy and Allen Shaw. Its distinct, contemplative visual language shuns the temptation of candy colours; it reminds one that picture books, as British illustrator Martin Salisbury’s remarked, are “a child’s first personal, private art gallery, held in the hand, to be revisited over and over again.”

Sometimes, the absence of an image also tells a story. Apna Apna Kaam, a story by Chandan Yadav featured in the February 2019 Cycle issue, is written in the voice of a boy whose father is a skilled pig-rearer. It recounts a day when the family goes out to catch pigs, the boy’s shame as villagers observe the tamasha from a distance, and the pig turning around and attacking the father. An editorial note at the end asks: “We asked two-three illustrators to draw something for this story. But they refused. Why do you think so?” The illustrators declined, says Shukla, 45, because they thought there was “too much violence in the story”. “Many of us think of children as too soft, as blank slates. But there was also the question: where is the story for the child in the classroom whose father rears pigs? Isn’t there anything to learn from, or be proud of in, his life? But more than that this story was for children to learn to sympathise with, and understand, him.” Bhopal-residents Shukla and Sablok started working together in Eklavya Books in 2007 to revive the popular children’s science magazine Chakmak. “Its readership had plummeted. We brought in an emphasis on original writing and artwork,” says Sablok. “We also realised that whenever big writers have written for children – the example of Bengali was before us – they have done amazing work. So, we approached hundreds of writers in Hindi, from Vinod Kumar Shukla and Asghar Wajahat to Gulzar and Priyamvad to write for us. They agreed. Vinodji at first was unsure but now writes only for children,” says Shukla.

Around 2015, both felt the need to break away. “One magazine for children of all ages was not enough. For little readers, especially, there needed to be a separate space – at that age you can either get interested in literature or be pushed away. So, we thought of Pluto,” says Sablok.

With financial assistance from Takshashila Foundation, Ektara was started in Bhopal in 2016 and has found a small, dedicated circle of admirers. “In championing language, and creating multiple reading opportunities in Hindi, from picture books, magazines to poetry posters, Ektara does an amazing job,” says Bijal Vachharajani, senior editor, Pratham Books, and a writer of children’s books herself.

Writer-lyricist Varun Grover singles out Ektara for “treating children as equals, as thinking beings”. He recalls Shukla ruing that there were not enough stories on Partition for children. That led Grover to tap into his family’s memories and write a tale about a radio left behind during the crossover from Gujranwala (in Pakistan). “Sushil brings in dark themes in a language and context which children understand. It completely breaks away from how Hindi children’s writing has been so far,” says Grover, who has guest-edited Cycle’s latest, a special issue on cinema.

Ektara shuns didacticism but is driven by a belief that children need to find a space free of the surveilling eye of society, the noise of conventions that takes them away from their true north. “As a child growing up in a small village in Hoshangabad, I would rarely go to school. We had time, friends, and the freedom to wander. Nowadays, I don’t see this open life for children, only many restrictions. So, literature or art – anything that preserves that freedom – is needed now more than ever,” says Shukla.

That freedom to wander and wheel away is what Cycle explores. A striking number of girls grace the covers of Cycle, riding bikes, lounging on the grass, or stopping to look at a semal tree in bloom. Sometimes, the images, too, need an incubation at Riyaz, an academy for illustrators that Ektara runs. “A lot of our artwork is done at Riyaz, but we have to talk to the illustrators, sometimes even fight with them to convince them to go beyond stereotypes. Most of the time, their first instinct is to portray a middle-class Hindu family. A woman who wears a sari and sindoor. A Muslim family where the background is green. We talk about this a lot, we tell them that your art needs to imagine a better world. Else, jo ho raha hai, wohi hota jayega (things won’t change),” says Sablok.

For Sushil Shukla, a commitment to a wide range of stories and characters comes from life itself. “Itna vividh sansar jo hai, toh diversity toh natural hai (diversity is natural when life is so diverse). The story of the Muslim family who lives near me is a part of my story, too. Why shouldn’t I learn about them? Even within one person, there is so much that is diverse. To know others, and through them, to know yourself – that is delightful. What we can do is enable a parichay (acquaintance) between you and the world, a kachnar tree, a spider, a lizard. If a child falls in love with a kachnar, who knows, he might stop it from being axed some day,” he says. “Iss duniya ko kholne wali, aur isse barabari se kholne wali bhasha (a language to open up the world equally) is what we are looking for,” he says.

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05