FARGO — The wildfire spread of Spanish influenza that was sweeping Europe and much of the United States in 1918 still hadn’t struck North Dakota and Minnesota as September faded with shortening days.

But the autumn ritual of watching leaves turning color as the weather crisped was overshadowed by people waiting anxiously for signs of the deadly contagion that had been circulating since March, fueled by massive troop movements during World War I.

“Spanish influenza hasn’t hit Fargo,” the Fargo Forum and Daily Republican reported on Sept. 27. Health officials called on residents to observe cautions and gave hints of what to expect.

“If you have a chill or aches and pains throughout your frame, a headache and a feeling of great prostration, there is a possibility, nay, even a probability that you will join the ranks of those entertaining within themselves the bacillus influenza, or even two of the creatures,” The Forum warned.

Years later, scientists would discover that the pathogen responsible for the Spanish influenza was caused by a virus — like the novel coronavirus infection now sweeping the globe — and not bacteria.

ADVERTISEMENT

The coronavirus pandemic is believed to be the most serious since the Spanish flu outbreak of 1918-19 killed an estimated 50 million people, including 675,000 in the U.S. The official death toll in Minnesota was more than 10,000 and more than 1,700 in North Dakota — estimates experts believe likely understate the grim count.

As it happened, on Sept. 27, the day Fargo residents were told the epidemic hadn’t yet hit, Minnesota got its first reported influenza case in Wells, between Mankato and Albert Lea in Faribault County.

That first case was a soldier who returned home on leave, according to the Minnesota Historical Society. Train travel and transoceanic ships carrying passengers and hundreds of thousands of troops enabled much of the rapid spread.

The day after Minnesota received its first official report, cases began appearing throughout the state.

The dreaded moment arrived in Fargo on Oct. 4, when Dr. Paul Borkness, the city’s public health officer, announced an eruption of more than 100 cases, including six patients who had developed pneumonia.

The Forum used a war analogy — invasion — to describe the explosive onset. Americans found themselves fighting what has been called the Other Great War against influenza on the home front. By Oct. 5, newspapers reported North Dakota was confronting thousands of cases.

By the second week of the epidemic’s arrival in Fargo-Moorhead, experience had shown that most of those who fell ill recovered. Still, levels of angst rose as the infection spread unabated.

A light-hearted story that ran on The Forum’s society page described people becoming panic-stricken from a sneeze or sniffle.

ADVERTISEMENT

“A large part of Fargo has been indulging itself for a few days speculating on symptoms,” a Forum writer wrote on Oct. 12. “A glow of interest lights up following a cat like sniff and a prospective victim announces, ‘I’ve got it.’”

Soon, however, as a rush of deaths mounted and the devastation became clear, any traces of levity disappeared from news reports. The tone quickly became one of alarm and desperation.

***

The influenza epidemic struck at an especially bad time. The nation was ill-prepared for a massive public health emergency because many doctors and nurses were involved in caring for troops, abroad and at home.

In both Minnesota and North Dakota, a third of the doctors and nurses were supporting the war effort, leaving communities with a severe shortage of health professionals.

“Coming as it did, at a time when physicians and nurses were scarce on account of so many enlisting in the service, the appearance in a community brought with it almost a state of hysteria,” a report by the North Dakota Board of Health noted.

The Red Cross did what it could. Teachers volunteered as nurses, and federal aid helped mobilize volunteer doctors. “It would have been a stupendous task to deal with the situation under normal conditions, but the war made things quite abnormal and help in many cases was hard to get,” the report said.

Doctors and nurses on the front lines of the epidemic were overburdened.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Physicians and nurses are near breakdown as epidemic result,” a headline in The Forum on Oct. 15 reported.

In Fargo-Moorhead, the need for nurses was especially acute at the North Dakota Agricultural College, where 150 men who were training for army service were sick with the flu. “New cases are developing every day,” an army plea for trained nurses said. “These young men are suffering and must have care. Trained nurses will be paid by the government.”

Whole families were incapacitated by the illness, “dependent entirely upon the irregular ministrations of neighbors,” the paper reported. “Physicians have been on duty 20 to 30 hours in a stretch, getting sleep only when they fell from sheer exhaustion.”

By then, Fargo, a city of 23,000 at the time, was dealing with an estimated 2,000 influenza cases, while Moorhead had 200 or 300. Even small towns sometimes reported more than 100 cases.

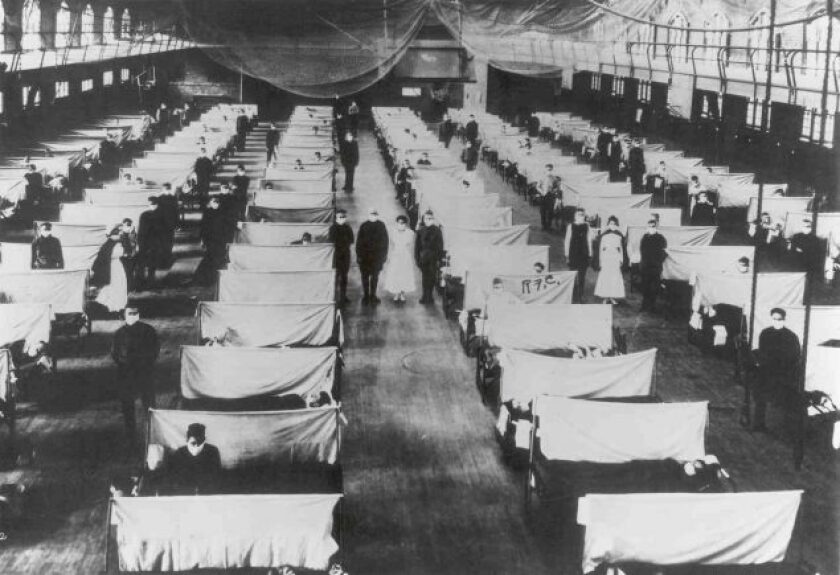

Many hospitals were overwhelmed. In Minneapolis, City Hospital became the designated care center for flu patients — and was so taxed by the onslaught that it had to be renovated and repainted after the epidemic passed. Half of its nurses became sick during the peak.

In many cases, the sick were tended at home or in makeshift hospitals. Bowman County, in southwest North Dakota, where the epidemic struck with “awful force” in late October, recorded 1,306 influenza cases, including 46 deaths.

Emergency hospitals staffed by teachers volunteering as nurses were set up in the towns of Rhame, Bowman and Scranton, which took patients whenever “the home condition was not good,” the North Dakota Board of Health reported in a roundup of local briefings filed in 1920 .

“The thanks of the county is offered these brave women and the county nurse, many of whom were ill of the disease, contracted while in the discharge of their duties,” the report said. “They served without compensation, as did various committees of citizens.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The illness progressed at lightning speed. In particularly aggressive cases, a person could seem perfectly healthy in the morning and be dead by evening.

Health officials advised people to rest, use handkerchiefs, go to bed when ill and call their doctors if symptoms worsened. As the epidemic spread, people were told not to gather in crowds, spit on floors or sidewalks or share drinking cups or towels.

Some of the most unconventional medical advice came from a doctor in Roseau County who recommended drinking squirrel soup, according to an example cited by the Minnesota Historical Society.

Funerals were delayed, sometimes because of the “almost utter impossibility of getting men to dig graves,” according to The Forum. Burials were restricted to immediate family members, the presiding pastor and the undertaker or his assistant. Casket viewings were prohibited.

In Minnesota, three funerals stemming from one wedding illustrated the hazards of social gatherings, which weren’t banned until the epidemic was raging.

A Marshall County couple married on Oct. 23. Days later, on Oct. 31, the bride died; the groom died the following day and, the next day, the priest who presided at their wedding also died.

“If you read through the obituaries at the time it’s just heartbreaking,” said Dr. Stephen McDonough, a Bismarck physician and former state health official who studied the influenza epidemic in North Dakota.

Nurses and other caretakers figured prominently among the casualties. “A lot of mothers died,” he said. One of the most haunting family tragedies he collected was in Fargo, where The Forum reported on Oct. 26:

ADVERTISEMENT

“Ten days ago the family of A.J. Anderson was happy and in the bloom of health. Today the mother and two sons lie side-by-side in Riverside Cemetery, and the third son lies still in death, all victims of the Spanish Influenza. Ester, aged 11 years, who is still in the hospital with the disease, and the father survive.”

Doctors and nurses, who took great risk in caring for the sick, sometimes died from their heroic efforts. In North Dakota, McDonough tallied two doctors and four nurses who died in military service as well as three doctors and 14 nurses who died in the state from influenza.

In Minnesota, in a tragic turn that seemed almost biblical, an enormous wildfire sparked on Oct. 10 near Cloquet coincided with the flu outbreak. The fire incinerated multiple towns in its path through the northern woods, killing 453 people and tens of thousands of animals.

The conflagration stopped only when the wind abruptly reversed direction, mostly sparing Duluth. A week later, the influenza epidemic struck the area that had just been ravaged by fire, leaving almost 12,000 homeless.

***

The Minneapolis Board of Health closed many establishments where people gathered in the city on Oct. 11, shuttering schools, churches, theaters, dance and pool halls. The decision to close the schools was contested in court, but health officials prevailed.

St. Paul was slower and less methodical in imposing control measures — a contrast that public health officials have studied as an illustration in how — and how not — to manage an epidemic.

In Minneapolis, the focus was on closing public places, while in St. Paul the strategy hinged on isolating individual cases.

ADVERTISEMENT

The doctor overseeing public health for the state of Minnesota, caught in the debate between the Twin Cities, asked a question that now confronts officials grappling with how to contain the coronavirus: “If you begin to close, where are you going to stop? When are you going to reopen, and what do you accomplish by opening?”

Finally, St. Paul city officials overruled their local public health director and on Nov. 6, almost a month behind Minneapolis, closed down the city.

Researchers determined that St. Paul, which was much more lax than neighboring Minneapolis, suffered a death rate that was almost 55% higher during the epidemic , according to the University of Michigan Center for Medicine.

Mark Peihl, archivist at the Clay County Cultural and Historical Society, researched how the epidemic hit the area and finds striking parallels with today’s coronavirus pandemic. Then and now, a patchwork of decisions determined how to contain the contagion.

“Essentially it’s the same as 1918,” he said. “It’s left up to state and local health departments and state and local authorities.”

Because of the lack of controls, the 1918 epidemic hit with intensity and went quickly, Peihl said.

“It came in like a house a’fire,” he said. “The hospitals were very quickly overwhelmed. Pretty much it was all over by the end of April, early May of 1919.”

But, he added, the three waves of the pandemic of 1918-19 show that multiple outbreaks spread out over time are possible.

So, Peihl said, if history is any guide, return outbreaks could follow the initial wave of the coronavirus.