MAVERICK LIFE SMALL SCREEN

This Weekend We’re Watching: Thought-provoking science-fiction movies

Science fiction often uses unfamiliar scenarios to frame very human questions. What links us? What divides us? When things go wrong, how do we respond? What is morality? What is humanness?

Given the times we’re in, science-fiction movies might be great avenues for introspection, as well as a fresh break from football World Cup reruns. This week, we’re looking at movies you could watch one after the other – because if you like one you might well like the other.

Her by Spike Jonze + Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind by Michel Gondry

Both available on Netflix

What will the future look like? The past. At least that’s the idea in Spike Jonze’s movie Her.

Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) works at Beautiful Handwritten Letters, writing couples’ correspondence. He lives in a near-future Los Angeles and has been a recluse since his marriage ended. To bring structure back to his life, he downloads an operating system and, to his surprise, finds that the OS is a “person”. Samantha (Scarlett Johansson) processes information at a computer’s speed, while experiencing emotion like anyone else. She quickly becomes more than a PA to Theodore, the two developing a companionship as he shows her what it’s like to be a human. As their relationship evolves, Samantha struggles with the practicalities of being in love without a body. At the same time, Theodore realises that Samantha is a more complex being than he had first understood her to be, and they each must try to overcome the differences in their programming.

Director Jonze’s vision of the future is a simple one. Take something retro and give it a sleek aesthetic. The result is a world we recognise, only it’s a little too elegant to be our own. Furniture is ’60s style, but understated; things are coloured in a fuzzy mix of pastel oranges and pinks; the philosophy of this world is equally familiar. There is still a sense of right and wrong, but people are less critical of each other’s lives.

And this latter element is what makes Her such a compelling story. It permits the kind of behaviour we would otherwise not allow. After all, if someone confessed to being in love with Siri, we would be sceptical at the very least, shocked more likely. But what if everyone did? What if you lived in a world where falling in love with an AI character was unremarkable?

Her does not ask where we are going as a society so much as challenges our current idea of what is real. From its opening scene, where we find Theodore composing letters between two elderly lovers, the film separates our idea of normality from how people in that society feel. To us, Theodore’s job is disingenuous; he writes the correspondences of persons he doesn’t know. We might wonder how he could understand what they feel, let alone be the person to imagine and dictate their love letters? To Theodore and the lovers, though, it feels real. Everything else is a matter of perspective.

Her reviews what humans value in love. Samantha and Theodore never physically meet each other, and they are fundamentally different. Yet, they enter a functional relationship.

In a world ultra-connected, social networking and our portable devices, like our phones, have become ubiquitous. Perhaps it’s time we consider how different our feelings for them are from “real” emotions.

If you enjoy Her, maybe try Wong Kar Wai’s 2046.

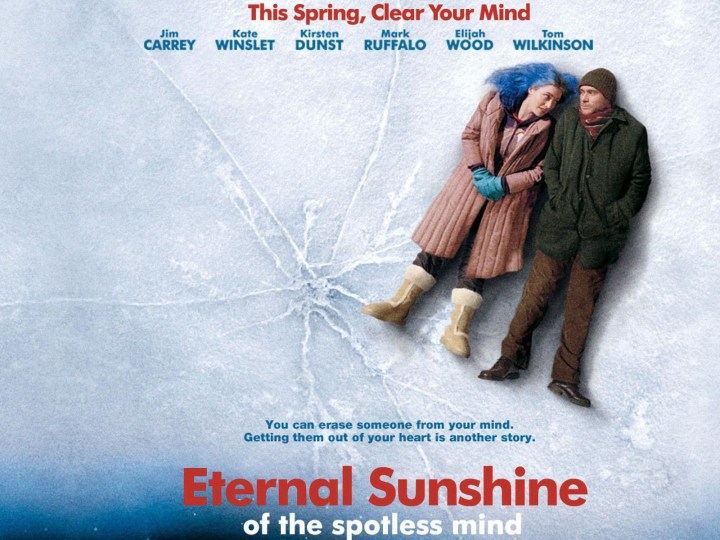

In Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Joel (Jim Carrey) and Clementine (Kate Winslet) meet on a train to Montauk, a seaside village on Long Island they have independently had an impulse to visit. In spite of their obvious differences, they click and spend two more evenings together; but this wasn’t the first time they had met. Joel and Clementine had actually been dating but, after an explosive fight, Clementine went to a company to have her memories of Joel erased. When he finds out, he decides to do the same, saving himself the pain of a break-up. As Joel’s memories are being deleted, he comes to realise that he still loves her… Only he can’t stop the process.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is even softer sci-fi than Her. Joel lives in our reality, the only difference is the existence of a machine that can erase people’s memory. Like Her, the focus is less on the fantasy of the film than reflecting on how people conduct relationships.

Joel’s memories are deleted in reverse order, starting from his break-up and moving backwards. As with most break-ups, the immediacy of the last fight casts a poor light over the entire relationship. Joel and Clementine’s personalities seem far too contrasting for them to do anything but clash. But as Joel’s erasure procedure wears on he rediscovers the reasons why he was so fond of her, and she of him. His memory erasure becomes an accelerated version of the aftermath of any break-up. He learns the importance of Clementine only as she fades from his life.

The film taunts the relationship between what we understand in the present and how memory, or disappearance thereof, affects it. It even ventures into the philosophy of determinism, which suggests that humans don’t really have free will, that all our acts are driven by predetermined influences.

***

Arrival + Blade Runner 2049, both films by Denis Villeneuve

Arrival is available on Amazon and Blade Runner 2049 on Netflix

Although both Arrival and Blade Runner 2049 are directed by Denis Villeneuve, there is no thematic link between the movies.

In Arrival, released in 2016, Doctor Louise Banks (Amy Adams), a reputable linguist, is lecturing at her university when 12 extra-terrestrial craft descend and hover above the earth. When the planet goes into lockdown, Louise is contacted by US Army Colonel GT Weber (Forest Whitaker) and asked for her help. He explains that, though they have “met” the aliens, neither species understands the other. Together with physicist Ian Donnely (Jeremy Renner), Louise is escorted to the alien ship, where they are introduced to the alien “heptapods”. Soon, Louise uses a whiteboard with words written on it, hoping to break the language barrier…

Until recently, the first-contact genre has presupposed that an alien arrival would be hostile. E.T. opened the door for more humanist approaches, suggesting that perhaps aliens valued the same things that we do, companionship and empathy. Arrival however, takes a step back and says: How would we know aliens’ intentions at all?

For years, film has assumed that aliens’ intentions would be only one way or the other. But it’s possible that nothing they do would be recognisable to us; not having experienced anything they had, their shape, their compound and their thoughts would be unfathomable. Would “peace” or “war” make sense to them, or would it be like asking someone to imagine a new colour? Are they self-aware or are they like bacteria that “live” in only the biological sense of the term?

For a film that swallows a sub-genre whole, it is surprisingly grounded. The way Amy Adams’ character focuses on disregarding the existential significance of first-contact and instead disassembles the mechanisms of language is remarkable. Her journey into teaching a language to aliens is thoughtful and philosophical: she ponders, how would you ask a heptapod its purpose if it doesn’t know that you’re asking?

Because communication between the heptapods and humans is so limited, scenes rely heavily on symbolism. For Villeneuve, the absence of dialogue is not a handicap but an opportunity to delve into scene construction; to convey obscurity, the heptapods exist behind a misted screen and the totality of their features are never quite revealed. Blocking is equally active. Louise and Ian, the two scientists, stand closest to the screen while the soldiers wait nervously at the space craft’s exit. It’s the age-old weigh-up between curiosity and fear of the unknown. They’re small details, but Villeneuve trusts the viewer to feel what isn’t explicitly said.

Arrival is more a meditation on the gaps in human understanding than a paranoid first-contact movie.

If you haven’t watched the original Blade Runner, now’s the time to stop reading and watch Ridley Scott’s 1982 sci-fi thriller.

Thirty years after the events of the original Blade Runner, Officer K (Ryan Gosling) has been tasked with tracking down and “retiring” old Nexus 8 “replicants” (humans bioengineered for use as slaves). K’s search takes him to the farm of Sapper Morton (Dave Bautista), where he finds a box of bones buried beneath a dead tree. Closer inspection of the bones reveals that they belonged to a replicant who had given birth, a technological anomaly. K, himself a replicant, is tasked with tracking down the child, whilst keeping the revelation a secret. But his progress is closely monitored by the Wallace Corporation (Jared Leto as Niander Wallace), the chief manufacturer of new replicants.

Remakes and sequels usually have bad reputation. Too often they limp along on the original movies’ ideas, adding little more than the special effects modern technology allows. But Blade Runner 2049 is faithful to the original only in that it too aspires to stand out in its genre. Both films are occupied with what the future will look like, but they reach their conclusions by very different means.

The sequel is dystopian grey, a steel and concrete apocalypse. The original was overcrowded, a neon cosmopolitan hive where cultures didn’t so much co-exist as clamber on top of each other. The former story takes place some 30 film years after the latter. But, significantly, Villeneuve has re-envisioned the artistry behind one of sci-fi’s most influential films. His view of the future is austere and indifferent. City-wide shots take in everything from solar farms to monoliths outside an abandoned Las Vegas. There’s no better sense of how small our lives could become than from watching K’s car become a speck between the many skyscrapers of the Los Angeles skyline.

For a film that runs what could seem as a daunting 162 minutes, it is eerily quiet. To this effect, Gosling’s performance is clinical and reduced. Though his K is obedient by design, there is something severe in how little he speaks. Such stripping down of sound and reactions infuses the few emotions K has with something bordering on sincerity and, were he not built to kill people, you might even see innocence.

The quietness is not without intent though. Like its predecessor, 2049 has a philosophical bent, only, instead of asking questions of ethics, it is preoccupied with K’s sense of self. What is the difference between being born and made? Why does one make you a person and the other not? Such existential reflections align with the film’s overall tone, where it’s difficult to imagine anyone finding meaning in so vast a world. ML

If you would like to share your ideas or suggestions with us, please leave a comment below or email us at [email protected] and [email protected].

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of Maverick Life delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider