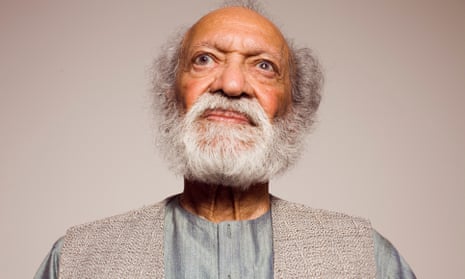

On the eve of what would have been his 100th birthday (he died at 92), Ravi Shankar remains one of the most famous and influential Indians of modern times, perhaps second only to Mahatma Gandhi himself. Every passing twang or drone of a sitar still evokes his name. As the man who brought the sub-continent’s classical music to the world and as George Harrison’s personal guru, Shankar enjoyed an almost saintly aura in the west. At home, public opinion was more tempered. India Today greeted his 60th birthday with the headline “Part sadhu, part playboy”, a nod to a globe-hopping lifestyle and Shankar’s complex, promiscuous romantic life.

In Oliver Craske, Shankar has attracted a biographer who understands the intricacies of classical Indian music and the labyrinths of a culture that believes there’s no enterprise that can’t be improved by being made more complicated – religion, language, family trees, music, railway timetables. His portrait of a restless, often melancholic genius is appropriately exhaustive, involving 130 fresh interviews and 100 pages of credits. There is much to explain.

Born into a Bengali Brahmin family, Shankar was of elite caste, though from a somewhat down-at-heel family. His father was a barrister, scholar and sometime impresario whom Ravi, his youngest son, didn’t meet until he was eight. The paternal role fell to Ravi’s eldest brother, Uday (nicknamed Dada), a celebrated dancer and choreographer who worked with ballet’s grande dame Anna Pavlova in London before founding a troupe that fused India’s classical and folk dances and became a cause celebre across Europe and the US in the 1930s.

It was a family affair, with mother and brothers on board and little Ravi along for the ride. His teenage years were spent in Paris, New York and Los Angeles, a saucer-eyed adolescent dandy, at ease taking in Duke Ellington or Cab Calloway at Harlem’s Cotton Club or in the company of movie stars – Marie Dressler wanted “to adopt him”. It wasn’t until Shankar was in his 70s that he also spoke about the sexual abuse he suffered in his teens.

Perhaps it was the unsolved murder of his itinerant father in London in 1935 that prompted Ravi to renounce life as a Hollywood hoverfly and submit to the rigours of music study in India, with sarod maestro Allauddin Khan as his guru, to sleep with the lizards and rise at dawn for hours of practice. Khan would deliver not just musical prowess but an arranged marriage with his daughter Annapurna, a relationship that would prove hugely troubled (though “not loveless” according to Craske).

Shankar’s talent was dazzling, and made him a young meteor of newly independent India. The cold war years found him as Prime Minister Nehru’s cultural ambassador, playing Moscow and New York, while he became musical director of All India Radio, newly established along BBC lines to bind the vast country together.

International renown grew with Shankar’s soundtrack for Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955), a milestone in Indian cinema that resonated worldwide. In the future Shankar would deliver dozens more soundtracks, including a lyrical score for Jonathan Miller’s 1966 BBC adaptation of Alice in Wonderland.

By then Shankar’s music was everywhere, drawing a unique confluence of western devotees. Violinist Yehudi Menuhin, darling of the classical west, cut a 1965 record with him. A young Philip Glass had his ideas revolutionised by working with him. A 1962 encounter with John Coltrane likewise changed the jazz giant’s direction and intensified his spiritual search. Rock’s nascent alumni were also entranced. The Byrds’ Eight Miles High was aptly described by its creator, Roger McGuinn, as “raga rock”. The Beatles were meanwhile exploring sitars and drones on Norwegian Wood and Tomorrow Never Knows.

George Harrison’s embrace of Indian culture, sealed by an idyllic visit in 1966 at Shankar’s invitation, changed everything, not least the Beatles themselves. Once the Fabs were into the east, everyone followed. Shankar’s appearance at the Monterey pop festival in June 1967 was triumphant – the footage remains joyous – though the pandit watched appalled as Pete Townshend and Jimi Hendrix destroyed their guitars. Music was meant to be holy. Shankar disapproved of drugs, but understood that his music had become the backdrop for young psychonauts who were, he said, mistakenly “looking for instant karma”.

At home, Shankar’s dalliance with the west brought accusations of compromising and polluting the sanctity of Indian music, though even his critics were impressed when he and Harrison arranged the Concert for Bangladesh in August 1971, a template for rock charity events.

After the west’s infatuation with the exotic east ebbed, Shankar remained the unassailable maestro and guardian of his country’s music, a relentless workaholic, though his personal life remained turbulent.

Estranged from his wife, he flitted between opportune liaisons and long-term affairs, like those with US concert promoter Sue Jones – with whom he had a daughter, the future star Norah Jones – and an old friend Sukanya Rajan, whom he would later marry. Their daughter, Anoushka, also grew into musical stardom. In his 80s, Shankar found himself doubly blessed.

Craske handles the niceties of Shankar’s personal life with diplomacy while staying focused on his subject’s musical mission and lifelong hunger for spiritual fulfilment. He wears his expertise lightly and his passion on his sleeve; a winning combination for a definitive work.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion