Jeremy Marre, who has died aged 76, was a British documentary maker specialising in films about popular music of every possible kind. Widely travelled, and with eclectic taste, he had a lengthy career that included adventurous documentaries about music in Africa, the Americas, the UK and the US, and profiles of artists such as Phil Spector, Roy Orbison, Youssou N’Dour and Count Basie.

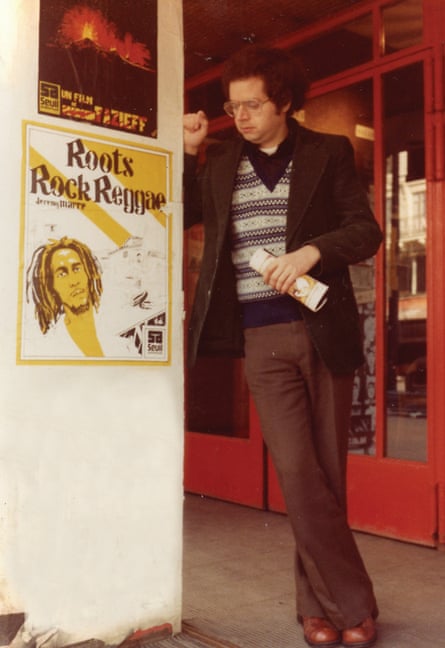

His first major success was Roots Rock Reggae (1977), which grew out of an earlier commission on the British reggae scene for the ITV arts programme Aquarius. Deciding that he needed to go to Jamaica to fully understand the music, Marre “scraped together some money” and travelled to Kingston, filming in lawless areas of the city. Threatened by some locals who accused him of being a CIA agent, he convinced them he was English only after they quizzed him about cricket. He returned with historic footage of artists including Bob Marley, Sly & Robbie and Jimmy Cliff, but still had difficulty in placing the film. As Marre explained in an interview with fRoots magazine in 2014, “the BBC said it was boring, and you can’t mix music and politics, while PBS in America turned it down as communist propaganda. But it won a documentary prize at Cannes and then the BBC wanted to show it. It was different to anything, with no presenter and no commentary.” It is now regarded as a classic film of the genre.

Mark Cooper, the former head of music television at the BBC, who worked with Marre on many of his films from 2005 on, called him “one of the key architects of the ‘rockumentary’ and music films”. “What all his films had in common,” Cooper said, “was great journalism, a desire to listen to the artist and a desire to give voice to the artist.”

Marre also had a knack of being in the right place at the right time. As a result he did not just chronicle popular music history, but helped to make it. He was in South Africa during the apartheid era, where he filmed black musicians long before the growing interest in world music brought them popularity in the west. Among those featured in Rhythm of Resistance (1979) was the Zulu choir Ladysmith Black Mambazo. Paul Simon saw Marre’s film and was so impressed that he decided to record with the group and other black South African musicians – and the result was his acclaimed 1986 album Graceland.

Albert Mazibuko, the group’s eldest surviving member, said: “Everyone points to our work with Paul Simon as the moment we became well known around the world. However most people do not realise that if it wasn’t for Jeremy Marre and his Rhythm of Resistance documentary, Paul Simon would never have known there was a Ladysmith Black Mambazo.”

Simon – with whom Marre would work later on a film about Graceland – said: “Jeremy had a deep curiosity and knowledge of a great deal of interesting music around the planet.”

Born in north London to Ivan Marre, a consultant dermatologist, and his Russian-born wife, Olga (nee Shlain), Jeremy was educated at Highgate school, north London. He graduated from University College London in law in 1965 and started reading for the bar before deciding he was more interested in film than law. He studied for an MA in film at the Royal College of Art but quit, finding it “pretentious”, and moved to the Slade School’s film department, where he was “happier … you could do what you wanted”.

He then took “odd jobs, from camera assistant to trainee assistant floor manager”, to build up his expertise and get a union card. In 1970 he received a BFI grant to make a short film inspired by Charles Dickens’s Pickwick Papers, Uneasy Dreams: The Life of Mr Pickwick.

Through his company, Harcourt Films, from the mid-70s Marre set out to film the music of the world for a series that would be branded Beats of the Heart. Over seven years he made 14 one-hour films, including Roots Rock Reggae and Rhythm of Resistance, that explored, as Marre put it, “the dynamic and often controversial role music plays within distinctive societies around the world … This music, sometimes called world music, is – in the words of reggae singer Jimmy Cliff – ‘the cry of the people’.”

The series covered popular music styles from Latin to Nigerian, Gypsy and Chinese. For Shotguns and Accordions (1983) he travelled to the marijuana-growing areas of Colombia. Many of the films were shown on Channel 4, all of them were released on DVD and video, and they were accompanied by Marre’s book of the same name.

Marre made his reputation through world music films but moved on to cover a wide range of subjects. His prolific output included The Left-Handed Man of Madagascar (1990), which explored ancestor spirit festivals and which won a New York film festival award, and On The Edge (1992), a four-hour C4 series on improvised music from around the world. Reigning in Hell (2006) investigated the feared American prison gang the Aryan Brotherhood. Marre also tackled more conventional subjects, such as with Classic Albums, a series that spanned 1997 to 2018, but always retained a distinctive film-making style.

Towards the end of his career, Marre made a series of profiles of musical celebrities, such as Otis Redding (2013) and Count Basie (2018). He used as little voiceover and commentary as possible, and never appeared in his own films, but instead used such techniques as getting an actor to voice the artist’s diaries. “He liked the films to breathe … and the subjects and contributors and archive to speak,” said Cooper. He was good at “winning the trust of his subjects because he was genuinely interested in them”. So he was able to persuade Redding’s wife and daughter to contribute to his profile, and discovered unseen archive from Count Basie’s estate “that gives a sense of Basie the man and the human being – and that’s vintage Jeremy”, said Cooper.

The singer Pauline Black of the British Ska revival band The Selecter, who was involved in Marre’s programmes Soul Britannia (2007) and Reggae Britannia (2011), said that “Jeremy’s singular skill was allowing British black folks to tell our own story in our own words”.

Marre even made an impression on “the godfather of soul’”, James Brown. Marre’s son Oliver recalled going to a Brown concert with his father when he was a teenager “and JB stopped the show and shone a spotlight on my dad. ‘Ladies and Gentlemen,’ he mumbled, ‘there are few men you can trust in this world. This man is one of them.’”

Marre married Diana Silman, a teacher, in 1970 and she accompanied him on many of his early filming trips. She survives him, as do their two sons, Oliver and Jesse, and four grandchildren.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion