- India

- International

Your guide to 10 socially relevant films from Bollywood

Alongside the escapist fare, Bollywood has always had a great parallel tradition of poetic realism, stories dealing with social issues and locating heroism in ordinary lives, starting with Bimal Roy and V Shantaram. Today, Aamir Khan, Akshay Kumar, Shoojit Sircar and many others combine entertainment with social commitment to produce meaningful cinema. Here's our list of 10 Hindi films based on a social subject, spanning decades.

In the first essay of ‘100 Bollywood movies to watch in your lifetime’ series, we explore 10 socially relevant films.

In the first essay of ‘100 Bollywood movies to watch in your lifetime’ series, we explore 10 socially relevant films.

Indian Express Entertainment is compiling a list of 100 Bollywood movies to watch in your lifetime, hoping to throw fresh light and perspective on them. We will explore one genre at a time, published every Friday with 10 films representing the said genre. We kick off the series with socially relevant cinema.

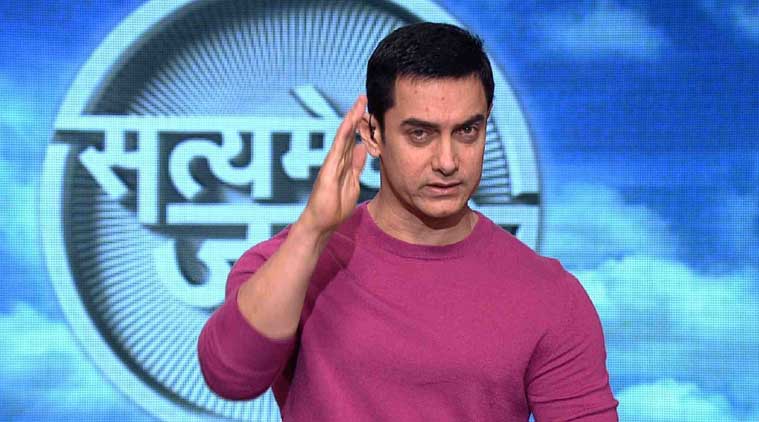

When talking about socially relevant cinema — stories with a social message, directly or indirectly — in the modern context, one name immediately springs to mind. That of Aamir Khan. Even though Khan sometimes strays into the ‘activist’ territory, no viewer can deny his deft appropriation of what appears to be ‘cinema of conscience.’ No coincidence then that, some years ago, at the height of Satyamev Jayate’s popularity the media hailed Khan as ‘India’s conscience-keeper,’ a mantle one isn’t quite sure if the perfectionist star worked methodically at acquiring or if it happened purely organically. From a 2012 Time magazine cover profile on Khan, you can discern his bleeding-heart interest in cinema as a medium of social change. Khan starrers such as Taare Zameen Par, 3 Idiots and Dangal prove that if you give audiences dollops of sugar in the form of entertainment, it’s likely they will swallow the bitter pill (read: social message). When asked by Time magazine about his role as an entertainer, the star replied, “It’s to bring grace to society, to affect the way people think, to make the social fabric stronger.’

Across six degrees of separation lies Akshay Kumar. In recent years, the action star of the 1990s has transformed himself into a go-to ideologue, giving us moral lectures on what it means to be an Indian. As far as box-office goes, the timely switch in image has paid off for him, as the success of Gold, Padman, Toilet: Ek Prem Katha and Airlift proves. If ever the government decides to initiate a ‘Patriot of the Year’ award, Bollywood’s two powerful Ks would be front-runners. Jokes aside, between Khan and Kumar, thanks to their outsized influence and mass following, a spate of issues like female feticide, honour killing, casteism, open defecation, menstrual hygiene and sanitation have got mainstream impact. While in one sense these commercial stars have served as social catalyst, there’s no knowing how much real change they have been able to inspire on the ground.

At the height of Satyamev Jayate’s popularity, the media hailed Aamir Khan as ‘India’s conscience-keeper.’

At the height of Satyamev Jayate’s popularity, the media hailed Aamir Khan as ‘India’s conscience-keeper.’

“All art can be a tool of social change,” Shekhar Kapur, whose gut-wrenching Bandit Queen is on our list, declared on his blog in 2009, adding, “Before cinema became so popular poetry was a great tool for the mobilization of emotion and sentiment. And passionate writings before that have caused revolutions. Some of the best art is born out of rebellion. Out of repression. Unless it is born out of yearning, spiritual or otherwise.” The filmmaker went on to argue that cinema can question, but “is unlikely to give effective answers.”

One of the greatest examples of cinema’s powers to reflect reality and demand social change came famously from the Italian neo-realists of 1940-50s. Canonical films like Open City (1945), Bicycle Thieves (1948) and many others that followed during Italian golden age were social and political commentaries on the bleak post-war realities as well as a broadside against Fascism. Novelist Cesare Pavese of The Moon and the Bonfires once remarked that the greatest Italian storyteller of his time was not a writer but a filmmaker. He was talking about Vittorio De Sica, a former actor whose radical transformation into a bard of tragedy was described by The Guardian as though “Hugh Grant were to suddenly metamorphose into Ken Loach.” While De Sica’s gritty work was changing the course of European cinema, one Indian was gaining reputation as the foremost idealist of his time. Bimal Roy, who was believed to be under the influence of Bicycle Thieves while making his very own classic, Do Bigha Zamin – a human poetry set against the backdrop of Calcutta’s rapid industrialisation – was a highly versatile storyteller and a part of the canon that includes the likes of Raj Kapoor, Mehboob Khan, KA Abbas and V Shantaram who believed in cinema’s innate power to reform. For these filmmakers, Bollywood wasn’t simply a dream factory designed to crank out musical fantasies and catering to popular taste. It was a collective responsibility to present the angst of the people and the nation, while very much retaining their own socialist voice. Their stories often drew parallel to the newly independent nation. They turned the spotlight on poetic realism, where the idea of heroism was subverted and where everyday stories were celebrated. Women were given extraordinary roles, more grit than glitter. Thus, Bimal Roy, Guru Dutt, V Shantaram, Mehboob Khan and Raj Kapoor came to be known as ‘auteurs.’

As Shyam Benegal wrote in the opening to Bimal Roy: The Man Who Spoke in Pictures, “Humanism was manifest in his selection of themes, like in Sujata, which is about a Harijan girl. Most of his films are consciously concerned with reforms or with social morality of one kind or another; he was not an escapist in any sense of the term. The family was the social unit through which were dealt issues like economic inequality and social oppression. His films are more from the viewpoint of a sympathetic outsider.” Even the devastating good looks of rookie Dharmendra could not deter Bimal Roy from focusing unwaveringly on the women in his films, most notably Nutan in Bandini and Sujata – two of his seminal works, both on our countdown. His evocative films remind us of the role women would play in independent India. According to Shoma A Chatterji, author of a book on Roy, “He belonged to a time and a space that honed his idealistic sensibility in the sense that all his films bear a social agenda without holding a flag aloft for ‘causes’ or without raising slogans.” The link between Bimal Roy (via Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Gulzar) and today’s Bollywood remains very much alive, as evident in the works of Aamir Khan, Rakeysh Mehra, Shoojit Sircar and Ashutosh Gowariker among others. It doesn’t look all that far-fetched when you consider Aamir Khan’s early association with Aditya Bhattacharya, grandson of Roy.

As part of the ‘100 Bollywood movies to watch in your lifetime’ series, we are exploring Bollywood’s ten socially relevant films that explains how some of Hindi cinema’s top filmmakers have skirted the safe and risk-free ‘escapist’ narratives to delve into the human stories, to scrub the sheen of the Bollywood fantasy to give us a dose of realism and much fodder for thought. Besides Bimal Roy and V Shantaram classics, there’s Yash Chopra’s under-seen Dharmputra, his second film made under the adoring shadow of B R Chopra and Sahir Ludhianvi. This was long before Chopra’s name became synonymous with Swiss Alps. Dharmputra, along with Dhool Ka Phool and Waqt, stands out as one of Chopra’s most powerful early masterpieces.

Scroll down our list to see more such timeless classics.

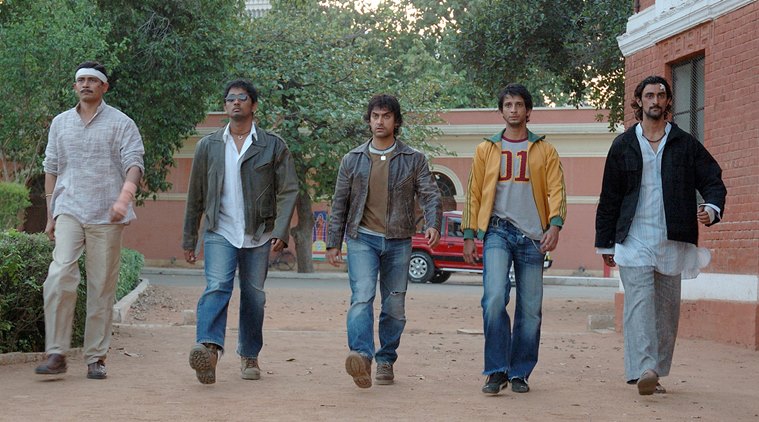

RANG DE BASANTI (2006)

‘Koi bhi desh perfect nahin hota, usse perfect bana na padhta hai’ — Karan Singhania

Bursting with patriotism, Rang De Basanti tackles contemporary youth culture.

Bursting with patriotism, Rang De Basanti tackles contemporary youth culture.

Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s Aks was critically acclaimed, but his invigorating odyssey into India’s historical past through the eyes of a group of recalcitrant Delhi university students established him as a filmmaker of repute. Starring Waheeda Rehman, Aamir Khan, R Madhavan, Siddharth, Sharman Joshi, Atul Kulkarni, Soha Ali Khan and Kunal Kapoor, the coming-of-age Rang De Basanti preempted the now cliche candle marches and other urban protests and movements. Never before has the youth been so passionately involved in the murky Indian politics. Bursting with patriotism, RDB tackles contemporary youth culture. When the spoilt youth find their historical purpose, after playing a gamut of Indian freedom fighters in a performance, by then RDB embodies the symbolic mantle of new India. Mehra, whose Delhi 6 was a commentary on religious bigotry, among others, is outrageously prescient here on many counts — the Jai Hind-spouting hyper-nationalism of Kulkarni’s Pandey, Jat machismo, the MiG issue that remains relevant in the Pulwama age and the privileged Siddharth’s sacrifice. His famous last words being (in a radio station takeover), ‘No country is perfect. You have to make it perfect.’ Also, the film’s biggest star, Aamir Khan lets lightweight Siddharth deliver the climax, a pattern you will see being echoed in Taare Zameen Par and Secret Superstar. A R Rahman’s extraordinary soundtrack and the legendary Lata Mangeshkar’s rare playback makes RDB not just bracingly watchable but also musically, one of the finest albums of the aughts.

SWADES (2004)

‘Tu chahe kahin jaaye, tu laut ke aayega’ — Javed Akhtar

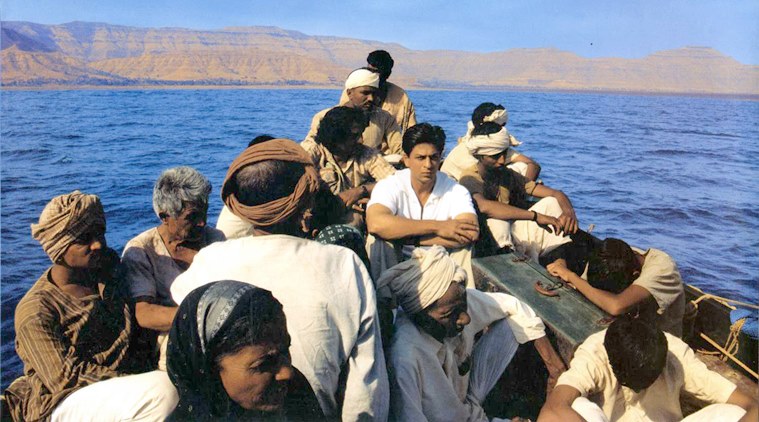

After watching Swades, you don’t miss Shah Rukh Khan’s mush-ball wizardry, the smooth-talking lover and designer brands.

After watching Swades, you don’t miss Shah Rukh Khan’s mush-ball wizardry, the smooth-talking lover and designer brands.

Ashutosh Gowariker’s greatest feat is to give us a Shah Rukh Khan stripped of all his superstarry glamour. Along with SRK of the Aziz Mirza-Kundan Shah days and Chak De! India (2007), Swades defies our expectations of a Shah Rukh Khan movie. After watching Swades, you realise you don’t miss Khan’s mush-ball wizardry, the smooth-talking lover and designer brands. He commands your attention with his idealism and utilitarianism, a character driven by a simple yearning to return home and do something meaningful with his life. He plays the NASA scientist Mohan Bhargava with the same sincerity he did the many Sunils and Rajus from his underdog years. Ashutosh Gowariker, who’s another link from the Mirza-Shah hangover, had last given us a monstrous hit in Lagaan. After the Oscar-nominated hit, he could have made any film he wanted. But the fact that he chose Swades gives the film a ‘straight from the heart’ quality. Watch it for turning the spotlight away from Raj-Rahul NRI cliche to another kind of a prodigal diaspora son who has his heart in the right place. Can an individual like Mohan Bhargava drive social change? Yes. But one village at a time, please.

BANDIT QUEEN (1994)

‘Ab meri ladai poore Thakur samaj se hai’ — Phoolan

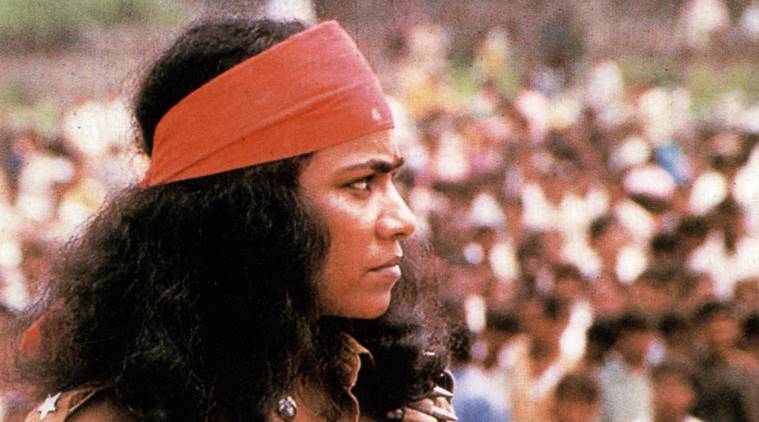

Bandit Queen traces Phoolan Devi’s stark transformation from a less-than-ordinary girl born into a poor, lower-caste family to a fearsome dacoit. (Express archive photo)

Bandit Queen traces Phoolan Devi’s stark transformation from a less-than-ordinary girl born into a poor, lower-caste family to a fearsome dacoit. (Express archive photo)

Explosive, unflinching, angry and soaked in bitter realism, Shekhar Kapur’s Bandit Queen opens with the feisty Phoolan, an 11-year-old bride being married off in exchange for a cow and cycle. The child bride fights off this exploitation, the beginning of an arduous and life-long battle against the crippling caste system and male domination. Throughout the film, she’s repeatedly raped, beaten and abused. Early on, she insists, “I am the daughter of Chambal.” Such is the social position of the woman in these ravines that men who so readily take advantage of her don’t want to even hear from her. “If you are talking about me, why don’t you hear from me,” she chips in, hiding behind her cousin as they confront a gang of dacoits. Bandit Queen traces Phoolan Devi’s (Seema Biswas) stark transformation from a less-than-ordinary girl born into a poor, lower-caste family to a fearsome dacoit. The festering wounds and insults strip her off her womanhood. Once in the gang, she throws a red band on her head and wins herself a mandate to become the leader. “Ab meri ladai poore Thakur samaj se hai,” she declares, in an an-male gathering. “Watch your mouth,” the male top brass thunders. “You are a woman and a mallah (lower-caste).” This lowest of the low — the ultimate outlier — returns to Chambal as a prodigal daughter to take on male vultures. By throwing in a startling scene about Phoolan breaking in a jewel shop only to give the stolen piece of jewellery away to a girl, about her own age when she was married off against her wishes, director Kapur once again reminds us that this is a story of a woman trapped in a man’s world and things would have turned out differently for Phoolan Devi had the men seen her the way she saw herself — a daughter of Chambal.

MANTHAN (1976)

‘Change doesn’t always bring progress’ — Mishra

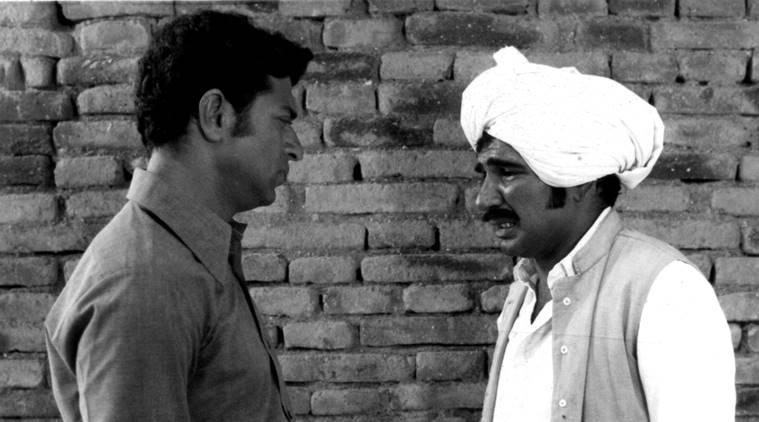

Dedicated to 5,00,000 small farmers who crowdsourced a penny each to make this film happen, Manthan’s larger symbolism is about the power of unity. (Express archive photo)

Dedicated to 5,00,000 small farmers who crowdsourced a penny each to make this film happen, Manthan’s larger symbolism is about the power of unity. (Express archive photo)

Dr Rao (Girish Karnad), the hero of Shyam Benegal’s Manthan, reminds one of another recent protagonist, Rajkummar Rao’s Newton. Like Newton, Manthan’s Dr Rao is depicted as an incorrigible idealist from the moment he sets foot on a remote Gujarati village, refusing the horse-carriage ride that is supposed to take him to his accommodation. He prefers to foot it, saving the ailing horse the trauma. A vet, he’s in the village to start a milk co-operative movement that will democratise the system, put everyone from the farmer to the seller on an equal footing and help bring the ‘white revolution’ of Dr Verghese Kurien’s dream to fruition. Mishra (Amrish Puri) who has built much of the economy around here is pessimistic about the movement from the word go, partly because he knows he stands to lose his mojo. “It’s fine to see idealism in the young because it goes away so quickly,” says Mishra, a man of experience, grinning. Mishra is just one of the obstacles Dr Rao faces in his earnest effort to uplift this village. Harijan leader Bhola (Naseeruddin Shah) is another. As Dr Rao and his team get mired in local politics, including a false accusation on Dr Rao himself, the noble intention is tested at every twist and turn. Dedicated to 5,00,000 small farmers who crowdsourced a penny each to make this film happen, Manthan’s larger symbolism is about the power of unity. Benegal’s casting is familiar, but a film like Manthan would have worked even without the who’s who (Smita Patil, Naseeruddin Shah, Girish Karnad, Amrish Puri, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, Anant Nag, Mohan Agashe) on the credit.

DHARMPUTRA (1961)

‘Samaj ko insaan ne banaya hai, samaj ne insaan ko nahin banaya’ — Dr Amrit Rai

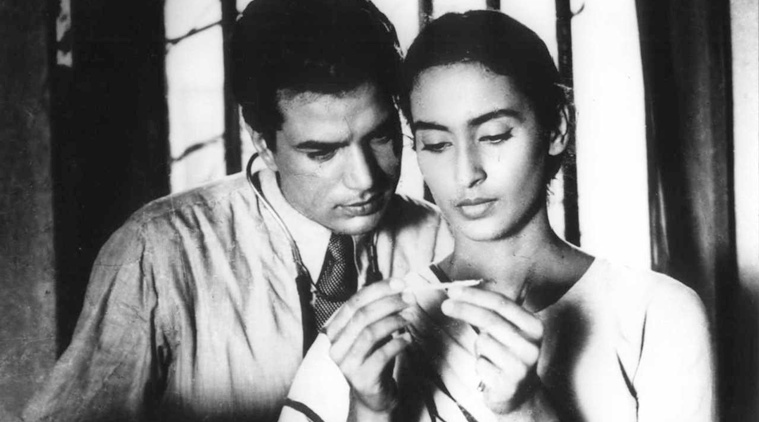

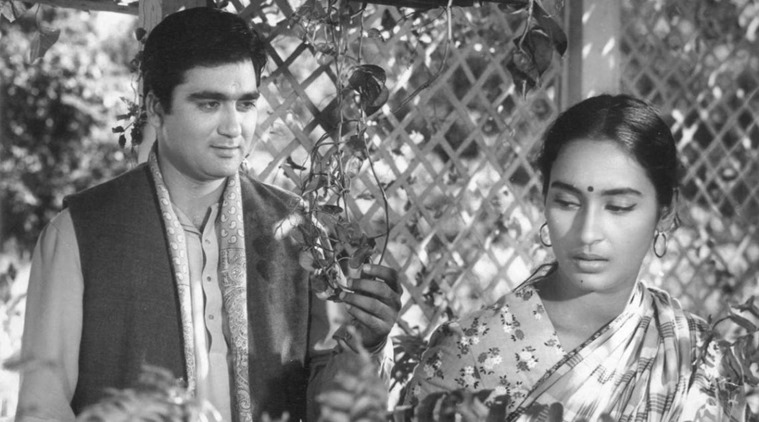

Shashi Kapoor, Mala Sinha and Nirupa Roy in Dharmputra. (Express archive photo)

Shashi Kapoor, Mala Sinha and Nirupa Roy in Dharmputra. (Express archive photo)

Those watching Yash Chopra’s first three films would have never predicted that this man, influenced as he was by stalwarts like BR Chopra, Sahir Ludhianvi and Akhtar ul Iman, would go on to become Hindi cinema’s king of romance. This is not to dismiss Chopra’s later so-called ‘lighter’ works, which includes dozens of masterpieces — Deewaar, Trishul, Kabhi Kabhie and Silsila to name a few. His debut film Dhool Ka Phool in 1959, Dharmputra in 1961 and Waqt in 1965 could be seen as a triptych, all three seem to flow from the very being of the Partition-wrecked Chopras. In Dhool Ka Phool, the great character star Manmohan Krishna sang, “Tu Hindu banega na Musalman banega.” He returns in Dharmputra, to prove that all the talk of diversity wasn’t just lip service. To save his beloved Muslim neighbour (one of the many small but memorable roles that Ashok Kumar has filled with his magnetic avuncular presence) from dishonour, Manmohan’s conscientious Dr Rai adopts the Nawab’s daughter Husn Bano’s (Mala Sinha) love child. That child grows up to be a Muslim-hating Hindu hardliner (Shashi Kapoor). It’s telling that the young Shashi Kapoor, Raj Kapoor’s son and a born star, chose to make this radical film his debut (as a leading man) when he could have so easily, with his soft-boy looks and pedigree, earned a romantic spot in a Subodh Mukherjee/Nasir Hussain musical. It’s also to Yash Chopra’s credit that the young filmmaker explored his own personal identity and that of the new nation’s, before flying Swiss Air to pioneer expensive Bollywood romance.

BANDINI (1963)

‘Mera apradh unke apradh se kaeen bada tha’ — Kalyani

Bandini starred Nutan, Dharmendra and Ashok Kumar. (Express archive photo)

Bandini starred Nutan, Dharmendra and Ashok Kumar. (Express archive photo)

The title Bandini (imprisoned) perfectly captures the essence of Kalyani’s (Nutan) life. She spends half the film in a women’s jail for poisoning her lover’s wife and the rest of it being held captive under revolutionary Bikash’s (Ashok Kumar) love. But Bimal Roy — never shy of sourcing liberally from books, particularly Bengali, a contagious literary disease that later on infected proteges Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Gulzar — might be making a larger point. Kalyani is a hostage to her own fate and doomed by it. Yet, a filmmaker with a sensitive touch, Roy is firmly on Kalyani’s side. He gives her agency that few directors setting their tale in colonial India would have allowed. There are two films in Bandini. Kalyani is torn between the love of Bikash (Kumar) and prison doctor Devendra (Dharmendra). The film opens with Kalyani taking up the responsibility of nursing an old inmate suffering from tuberculosis. She volunteers hard labour just as readily. Kalyani rejects Devendra’s advances. Her past will ruin her present, she is afraid. All she wants is repentance and she will do anything for it. Don’t miss the recurring, ‘All’s well’, as a jail hand assures everyone of safety from time to time. But is all really well? The progressive-minded Devendra has fallen in love with Kalyani’s sincerity, purity and beauty and is willing to accept her, whatever chequered her past. All the while, Bikash’s ghost hangs over the narrative like a shadow. The second film within Bandini deals with Kalyani’s blissful domestic life back in her village and her time with Bikash. She writes this episode of her life down in a notebook for the jailer, as if rendering it into posterity while the chapter featuring Devendra falls into obscurity. The two men in Kalyani’s life, Devendra and the older Bikash, are described as ‘devta-like.’ But the bitter irony is that Kalyani, with her quiet dignity and suffering, is the real goddess here. In the end, she makes a choice to tend for an ailing Bikash, leaving Devendra with no emotional payoff. In exploring these emotional conflicts through the eyes of a woman, Bimal Roy makes it clear that Kalyani has to break the shackles of freedom on her own, just like India of 1947.

SUJATA (1959)

‘Tum mein sabse bada gunn yehi hai, Sujata, ki tumme koi gunn nahin’ — Adhir

Sujata tackles the caste problem in a way that’s neither preachy nor heavy-handed. (Express archive photo)

Sujata tackles the caste problem in a way that’s neither preachy nor heavy-handed. (Express archive photo)

Once again, the title of a Bimal Roy film whispers its irony, rather than scream out — dropping lightly on you, just like a dew falls on Sujata’s serene face. Lower-caste Sujata (a Hindu name for a girl from a ‘good family’) is grudgingly adopted by a Brahmin clan. Engineer Upendranath Chowdhury and his wife Charu look after her, but the love is conditional. She’s always “daughter-like,” never THE daughter. Her grown-up version is played with subtlety and grace by Nutan, a rare star who had the gift to mute down the melodrama. The same could apply to Roy himself. Growing up alongside the Chowdhurys’ blood daughter Rama (a naive and playful Shashikala, who acts pretty much like the female version of Sunil Dutt’s Bhola from Padosan), Sujata knows her place both in this family and the upper-class society they inhabit. In one scene, stung by Adhir’s (Sunil Dutt) love, she meanders into Rama’s room. Picking up her magazine, she sits on her bed, perhaps trying to imagine a life like her far luckier sister’s. With references to Gandhi and Gautam Buddha, Sujata tackles the caste problem in a way that’s neither preachy nor heavy-handed. The story sticks faithfully to protagonist Sujata, from birth to marriage, from a young girl to a mature adult and from the ostracised to the accepted. How many filmmakers can say it with such beauty and simplicity? PS: S D Burman’s use of Bhatiyali (boat man’s folk songs) is superlative in both Sujata and Bandini. Poignant and perceptive, music from these two films have had an immeasurable influence, especially on the Hindi middle-of-the-road cinema music. Think of Anand, Guddi, Mili and Ijaazat.

NAYA DAUR (1957)

‘Hum chaahein toh paida karde chattaanon mein raahein ‘ — Shankar

Dilip Kumar evoked rural India mannerism with such delicious lyricism in Naya Daur. (Express archive photo)

Dilip Kumar evoked rural India mannerism with such delicious lyricism in Naya Daur. (Express archive photo)

This BR Chopra classic can be seen as an allegory on modern India. Kundan (Jeevan), the abrasive, city-returned son of a factory owner inherits a vast business. His outgoing father was a kind-hearted man whom the villagers looked up to. Now in his place, capitalist Kundan wants to run the show his way. Pro-industrialisation and a true moderniser, he is devising ways to introduce a bus service that will drive the horse carriages out of business. One such horse cart-puller is the village charmer Shankar. That’s Dilip Kumar, evoking rural India mannerism with such delicious lyricism that in the hands of a lesser actor, Shankar would have passed straight into caricature. You can see why every actor, from Amitabh Bachchan to Govinda, has been inspired by this particular role. To quote Javed Akhtar, “With time, we are understanding the nuances of Dilip Kumar’s acting. His greatness is only dawning upon us. And the process is still on.” Even though a minor classic in his diverse body of work, Naya Daur can be said to be a part of that “process.” The thespian is paired here with Vyjayantimala, the village belle, and a fine turn by Ajit as his best friend. As Shankar clashes with the formidable Kundan, in a David-versus-Goliath, Naya Daur reminds you — echoing its anthem (‘Saathi haath badhana’) — that man’s will can do wonders. In a classic man-machine conflict, Shankar’s tonga accelerates at breakneck speed to outdo Kundan’s bus. It’s an exciting climax and an even exciting film, full of splendid touches, fun chemistry between Kumar, Ajit and Vyjayantimala and not to forget, O.P Nayyar’s chartbuster music.

DO AANKHEN BARAH HATH (1957)

‘Sarkar ne tum chhe logo ko mere hawale nahi kiya, balke meri zindagi tumhare hawale kar dee hai’ — Adinath

V Shantaram in Do Aankhen Barah Hath. (Express archive photo)

V Shantaram in Do Aankhen Barah Hath. (Express archive photo)

Just as Bimal Roy was a product of New Theatres and shaped by its literary aesthetics and social commitment, V Shantaram was a reform-minded filmmaker from Prabhat Film Company that believed in cinema’s potential for social impact. Much of Prabhat’s work was underpinned on mythological epics and social issues. Shantaram’s own body of work is a fine example of optimism and hope. In Do Aankhen Barah Hath, Shantaram plays Adinath, a committed jail warden who gets six hardened criminals out of prison. The idea is to reform them and thus, make a good example out of them. He reads them ‘Aye maalik tere bande hum,’ cooks for them and trains them, hoping for a transformation. “There are no locks and keys here,” he tells the inmates. “You are free.” But that’s because, as he repeatedly emphasises, he trusts them. Such is his dedication towards them that he considers himself the seventh convict. Adinath, or ‘Babuji’ as the men call him, departs the scene before he can see his experiment succeed. But the inmates swear to keep the ‘Azad Nagar’ he created alive even after his death. Watching today, many new viewers might find Do Aankhen Barah Hath’s moral lessons not so subtle, but the film was ground-breaking in its time and many of its social commentary evokes contemporary resonance even though the methods to drive home that point may have long changed.

Also Read | Femme fatale, avenging mom, serial killer armed with an iron rod: Welcome to Bollywood’s heart of darkness

NEECHA NAGAR (1946)

‘Gareebo ke khoon se holi khelta hai’ — Balraj

Neecha Nagar won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival in 1946

Neecha Nagar won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival in 1946

In Kaala, Rajnikanth’s politically-charged 2018 blockbuster, politician Hari Abhayankar (Nana Patekar) wants to scrub the dirt off Mumbai’s Dharavi and turn it into Shanghai. He comes up with a redevelopment scheme to instal tall towers on the slums, quickly transforming Mumbai’s ill-reputed ‘neecha nagar’ into a snazzy ‘ooncha nagar.’ Something similarly devious was going on in the mind of the villainous Sarkar (played by the Urdu-speaking Rafi Meer, who moved to Lahore after Partition and started a theatre group) from Chetan Anand’s debut Neecha Nagar. The theme of land politics is a lived reality for today’s Mumbaikars, to whom the film might find resonance. The influential Sarkar has his eye on the land and pulls every trick in the book to evacuate the tenants, including cutting off their water supplies. The residents of Neecha Nagar protest hard to stop the Sarkar-motivated ‘nallah’ from being diverted through their slum. Eventually, the biggest blow to Sarkar comes when his daughter leaves him to empathise with the Neecha Nagar residents and their movement. Inspired by Maxim Gorky’s The Lower Depths, Anand’s rookie film, with nods to Eisenstein, Pudovkin and German Expressionism, went on to win the Grand Prix for the best film at the Cannes Film Festival in 1946. Reportedly, the film was lost after that and remained in obscurity until Satyajit Ray’s cameraman Subrata Mitra discovered it in a junk pile and duly deposited the print at the National Film Archives of India. Years later, Chetan Anand received a letter from a young film buff citing Neecha Nagar as one of the films that inspired him to make his own. That was Satyajit Ray.

(Shaikh Ayaz is a writer and journalist based in Mumbai)

Photos

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05