Which coronavirus patients will get life-saving ventilators? Guidelines show how hospitals in NYC, US will decide

NEW YORK — The coronavirus pandemic has added an important duty to Dr. Mitchell Katz's job as head of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, the nation's largest public health care system.

Before going to sleep after marathon days, he checks to make sure each of the 11 acute care hospitals he oversees has enough ventilators to help critically ill COVID-19 patients breathe.

"That will not go beyond Sunday, when we will exhaust our supply," Katz said during a news conference earlier this week with New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio.

But on Thursday, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said the state had shipped 400 ventilators, providing a few more days of capacity.

Still, the need remains dire, and growing, as coronavirus sufferers crowd hospitals.

The shortage is forcing health care officials in New York City to weigh ethical questions about who should get priority. Their counterparts across the nation may soon face the same dilemma as the pandemic surges.

US coronavirus map: Tracking the outbreak

Sign up: Get daily coronavirus updates in your inbox

COVID-19 information: Latest coronavirus updates

There are no national guidelines for allocating scarce health care resources such as ventilators and hospital intensive care beds in times of crisis, though a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisory committee has published ethical considerations that states could use in allocating ventilators during a health crisis.

Many states have created their own plans to guide emergency decision-making.

Some were designed to deal with influenza outbreaks, both a moderate epidemic and a global crisis on the order of the 1918 flu pandemic. Those guidelines are being adapted to help allocate increasingly scarce critical care resources for the thousands of COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals.

"It's very simple math. We don't have enough equipment for everyone who needs it," said Dr. Calvin Sun, an emergency care doctor who covers shifts in hospitals across New York City.

New York City faces ventilator shortage

About 2,500 to 3,000 additional ventilators are needed to get all city hospitals through next week, de Blasio said.

The city hopes to get some of them from the roughly 10,000 that President Donald Trump has said are in the nation's Strategic National Stockpile for distribution to coronavirus hotspots.

Friday, de Blasio pleaded for additional machines, stressing that his city is the U.S. epicenter of the pandemic.

"They should have had more ventilators," Trump said Friday night when asked about the issue.

Separately, questions have been raised about the condition of the federal ventilators. California Gov. Gavin Newsom tweeted last week that 170 of the units had arrived broken. More than 2,100 of the stockpile machines didn't work because they weren't maintained, The New York Times reported.

USA TODAY investigation: US exported millions in masks and ventilators ahead of the coronavirus crisis

Unprepared: US never spent enough on emergency stockpile, former managers say

Not in stock: Reusable respirators protect doctors and nurses against coronavirus. They aren't in the national stockpile.

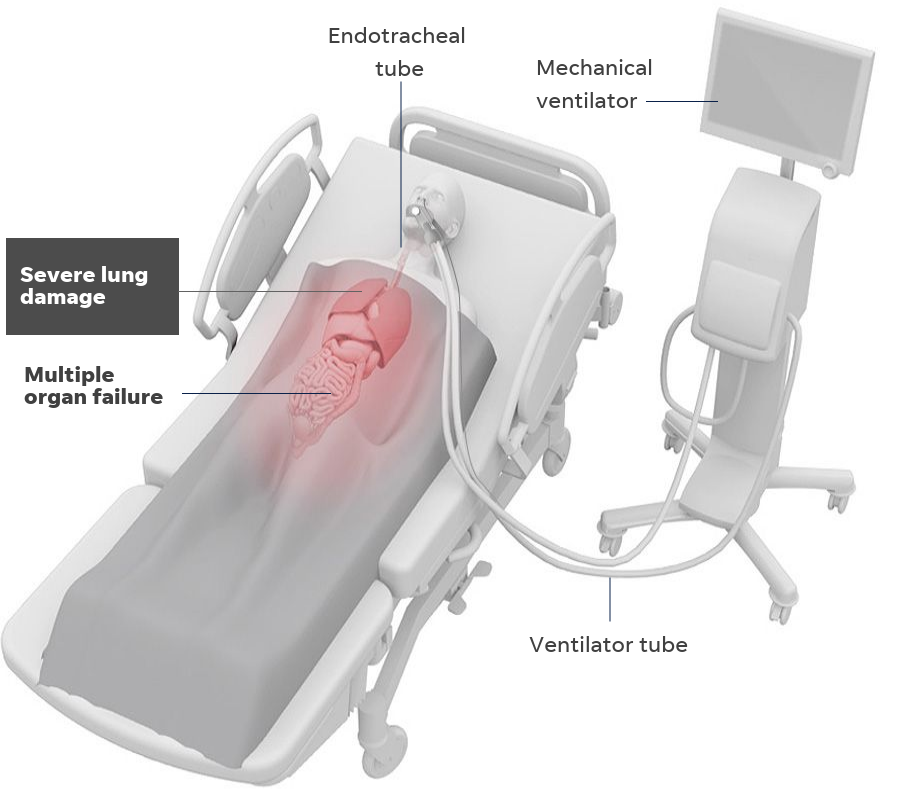

"If a person comes in and needs a ventilator and we don't have a ventilator, the person dies," Cuomo said Thursday. He warned that the state's supply could run out in six days and outlined plans to repurpose other machines for COVID-19 patients.

"That's the blunt equation we're dealing with."

Friday, Cuomo issued an executive order authorizing the state's National Guard to bring unused ventilators from upstate hospitals to those in New York City. He estimated that would bring in several hundred units. The state will return the units later or pay for them.

"If they want to sue me for borrowing their excess ventilators to save lives, let them sue me," said Cuomo.

The state received some welcome and unexpected relief on Saturday. The government of the People's Republic of China facilitated a shipment of 1,000 ventilators that were expected to arrive at John F. Kennedy International Airport within hours, Cuomo announced. He thanked Alibaba Group co-founders Jack Ma and Joseph Tsai, along with Huang Ping, the ambassador at China's New York consulate.

We finally got some good news today.

The Chinese government helped facilitate a donation of 1,000 ventilators that will arrive in JFK today.

I thank the Chinese government, Jack Ma, Joe Tsai, the Jack Ma Foundation, the Tsai Foundation and Consul General Huang.— Andrew Cuomo (@NYGovCuomo) April 4, 2020

After hearing about New York's ventilator scarcity, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown sent 140 units. Cuomo called the unsolicited loan kind, and smart, because the move will help check the pandemic that threatens the entire nation.

New York hospitals have implemented other emergency measures, including using a single ventilator to help two COVID-19 patients breathe. Known as splitting, the procedure can be risky for some patients.

Hospitals are repurposing anesthesia machines as ventilators and are using bilevel positive airway pressure machines, which are sometimes used to treat obstructive sleep apnea.

Oregon doesn't have everything we need to fight COVID-19 — we need more PPE and testing — but we can help today with ventilators. We are all in this together.

— Governor Kate Brown (@OregonGovBrown) April 4, 2020

How is life-saving care allocated in a major crisis?

Deciding who gets priority for ventilators and other critical health care equipment should be addressed in advance, not in the midst of a pandemic, said Nancy Berlinger, a research scholar at The Hastings Center, a bioethics center in Garrison, New York.

"When you have a situation where you're going to have more patients than there are resources, you need a way to allocate those resources fairly," Berlinger said. "No one wants to use these plans. But no one thinks this should be an ad hoc decision, either."

A group of medical ethics experts offered some recommendations in a New England Journal of Medicine paper in late March.

They said the dwindling number of ventilators and available beds in hospital intensive care units during the coronavirus pandemic "may mean giving priority to younger patients and those with fewer coexisting conditions."

"How many years of life you save is a relevant ethical concern," said Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, one of the paper's authors and a professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine.

How to help: Mister Rogers said to 'look for the helpers.' Here's how to help amid coronavirus panic.

Ventilators, intensive care beds and other emergency health care resources "should go first to front-line health care workers and others who care for ill patients," the experts recommended.

And patients with similar prognoses should get access to the emergency resources through random selection, they said.

States dust off plans for influenza pandemic

The word "coronavirus" doesn't appear in states' emergency plans. Emanuel, the bioethics expert, declined to discuss individual plans, but said "there are certainly some that are better than others." USA TODAY reviewed a sampling of 10 plans from around the country.

In Colorado's plan, a patient meets the "exclusion criteria" — meaning that limited resources will be withheld — if he or she suffers from severe dementia, incurable malignancy or end-stage multiple sclerosis, or if the patient is at least 90 years old.

In Arizona and Alabama, a color-coded chart helps doctors determine which patients are eligible for intensive care or a ventilator. The coding is based in part on an assessment of the extent of a patient's organ failure, a protocol cited in several of the state plans.

Patients assigned green or yellow get treatment. Those coded red may be excluded if resources are exhausted. Those coded blue begin "palliative care" designed to reduce suffering prior to death.

Missouri’s plan warns bluntly, “There will be marked shortages of staff and resources,” and it says assistance from other states and the federal government will be limited. Similarly, the Illinois plan says there may be shortages of "gloves, respirators, ventilators and laboratory testing supplies."

Mississippi's pandemic influenza plan says hospitals might be required to report every 12 hours on available beds, including intensive care unit and ventilator beds, during later stages of a major health crisis.

The Minnesota Department of Health's strategies for scarce resource situations recommend patients remain on ventilators if they have a low likelihood of dying, a good medical prognosis, no significant underlying diseases and breathing improvement over time.

And if a patient doesn't meet those conditions, the ventilator could be moved to someone else.

A Minnesota Pandemic Ethics Project panel spent months studying "rationing protocols" to cope with an illness far deadlier than the seasonal flu, one capable of killing 38,000 residents. Like other states, the panel ruled out life-or-death decisions based on gender, race, religion, citizenship and a patient's finances or societal value.

The panel concluded that health care and public safety workers should receive priority care. It might be appropriate to prioritize children in a situation where adults and children both need scarce equipment, the panel said.

And, if it came down to two patients with equal scores needing a single piece of equipment, the panel said the decision should not be made on a first-come, first-served basis.

"A more random technique, such as a lottery or flipping a coin, should be used instead," the panel advised.

A New York state task force spent two years drawing up ventilator allocation guidelines for a 2015 report. Some other states drew on the recommendations when they drew up their own plans.

The recommendations suggest a random process for deciding who gets a ventilator and evaluating patients after 48 hours and 120 hours on the machines.

A first-come, first-served process could disadvantage lower income patients who might not have as much information about a pandemic, as well as minority communities "who might initially avoid going to a hospital because of distrust of the health-care system," the guidelines say.

A patient's doctor should not make the allocation decision, the guidelines recommend. Instead, a triage panel or officer should decide.

In New York, the hypothetical has become real

Thursday night, as the ventilator shortage in New York City neared a crisis point, the president of the Medical Society of the State of New York issued guidance for doctors. Dr. Art Fougner wrote that some emergency doctors faced with ventilator decisions have said they've been told the equivalent of, "Use your best judgment. You're on your own."

Instead, he recommended referring to the state's ventilator guidelines. Hospitals, he wrote, should empower their ethics committees to have a system "to respond urgently to requests for guidance when the need arises so that no physician need bear this terrible burden alone."

Those guidelines appeared to be little-known among New York City hospital staffers before the coronavirus pandemic, said Sun, the emergency care doctor. No longer.

"Now, it's being circulated around and discussed by everyone," Sun said after getting off a 12-hour shift Wednesday night. "They can see what's happening. Hospitals are now ending shifts with one or two ventilators" available.

Although he normally prefers short summaries of medical issues, Sun said he appreciates the research that went into New York's ventilator allocation guidelines.

He warned, however, that decisions about placing patients on ventilators — or removing them — must be made quickly.

"I don't have the luxury of waiting hours," Sun said. "I have minutes or seconds."

Contributing: Jayme Fraser, Joseph Spector

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Coronavirus ventilator shortages may force tough ethical questions