- India

- International

Explained: How Covid has flattened prices, shifted demand curve for agri-commodities

Lockdown has led to demand destruction similar to demonetisation even for commodities such as potato and milk that were till recently in short supply

Lower production, yet lower demand, leading to fall in prices. (Express Archive)

Lower production, yet lower demand, leading to fall in prices. (Express Archive)

While there is debate on how much the lockdown has helped in “flattening the Covid-19 curve”, one thing is clear: It has led to a flattening of prices through a “leftward shift in the demand curve”.

The best way to illustrate this is through two agricultural commodities — potato and milk — that were experiencing significant production shortfalls. In ordinary circumstances, it would have resulted in prices shooting up at this time. Instead, they have remained flat or even collapsed, thanks to the demand destruction from lockdown.

Fewer takers for potato

Take potatoes, of which cold stores across India have stocked only an estimated 36 crore bags (of 50 kg each) from the main rabi (winter-spring) crop harvested in February-March. This was as against 48 crore in 2019, 46 crore in 2018 and the record 57 crore bags of the 2017 post-demonetisation crop.

“Production this time has been much lower, which should have translated into far better prices than last year. But the lockdown has upset our calculations,” said Karamveer Jurel from Khandauli village in Etmadpur tehsil of Uttar Pradesh’s Agra district. This farmer has harvested 28,000 bags from 120 acres, 20 of his own and the balance leased land. Like many growers, he has deposited the bulk of his produce in cold stores for making staggered sales from April to December.

Till early-April, when the lockdown’s impact was still to kick in, mota aloo or regular large potato was selling from Agra’s cold storage units at around Rs 21 per kg. But it is now fetching Rs 18 and Jurel expects rates to drop by another Rs 4-5/kg towards mid-June. “Nikasi (offtake) is down. Hardly 500 trucks (each carrying 400-odd bags) are being loaded daily from Agra zone (which includes Aligarh, Mathura, Hathras, Etah, Firozabad and Etawah districts), compared to the normal 800,” Jurel noted.

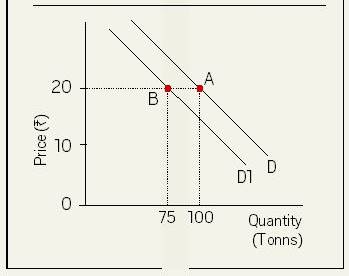

When demand curve shifts leftwards.

When demand curve shifts leftwards.The reason is simple: With hotels, restaurants and street food joints shuts and no weddings or other public functions taking place, consumption of potato-based snacks — from aloo chaat, tikki, samosa, pav bhaji and masala dosa to French fries — has taken a beating. Lower demand has, hence, caused prices to fall.

Read| Ahead: bumper crop, multiple challenges

The above price decline, though, isn’t the usual one that economists term “movement along the demand curve”. Such movement involves a reduction/increase in quantity demanded only on account of an increase/decrease in price, and vice versa. What is being seen now, however, is the demand curve itself “shifting”. That, in turn, is due to the collapse of institutional or business demand for potatoes. When aloo is being consumed only in home kitchens, there is less overall demand than before even at the same price.

Thus, in the chart, 100 tonnes was being demanded at Rs 20 pre-lockdown. But with the original demand curve shifting from D to D1, only 75 tonnes (these are purely illustrative numbers) would be bought at the same price. The quantity demanded has been affected by something other than price — in this case, the shutdown of businesses.

The worries, now and later

The ultimate sufferers are farmers. Agra zone’s cold stores alone have stocked about 8.7 crore bags of the current rabi crop, lower than last year’s 10.5 crore and the all-time-high 13 crore bags of 2017. “The last three years were bad, when we could barely recover our production cost of roughly Rs 12 per kg, which includes Rs 115/bag (Rs 2.3/kg) cold store expenses. When prices touched Rs 25/kg in end-December, we thought 2020 will be the year to recoup past losses. The lockdown’s impact will be deergh kaleen (long-term), just like notebandi (demonetisation). Then, it was cash. Now, it is incomes that will take time to recover,” Jurel predicted.

According to Mohammad Alamgir, general secretary of Agra’s Potato Growers Association, the situation may worsen with kharif potato plantings during May-August in Karnataka (mainly Hassan, Chikmagalur, Belgaum and Chikkaballapur) and Maharashtra (Pune, Satara and Nashik). “They should be discouraged from cultivating aloo, as it will benefit neither them nor us. Once their crop (of 65-70 days, unlike the 110-120 days varieties grown in UP) arrives in the market, prices will hit rock-bottom,” he said.

The Agra zone, along with MP (Indore, Ujjain and Shajapur districts) and Gujarat (Banaskantha and Sabarkantha), meets much of the potato demand in Delhi, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and South India. UP’s Kanpur zone (especially Kannauj, Farrukhabad and Barabanki), West Bengal and Bihar feed the entire East and Northeast India markets.

Editorial | There must be proper marketing of bumper rabi crop, planning for kharif. Much depends on it

“Something should be done about demand. Why can’t the government allow APMC (agricultural produce market committee) mandis to open 24 hours? Would that not enable social distancing and make buyers more confident about going to the markets, which are currently overcrowded and open for only a few hours?” said Jurel.

Shift with milk, too

The leftward shift in the demand curve is even more obvious vis-à-vis milk. 2019-20 saw India’s milk production, perhaps, fall for the first time in decades. Till mid-March, there was talk of the country actually having to import up to one lakh tonnes of skimmed milk powder (SMP). Before the lockdown, dairies were selling SMP at Rs 300-310 per kg and cow butter at Rs 320 per kg. Those prices have not just flattened, but crashed to Rs 170 and Rs 230/kg levels. Many dairies have further slashed procurement prices. Only two months ago, farmers in UP were getting Rs 43-44 per kg for buffalo milk containing 6.5% fat and 9% solids-not-fat, which has since come down to Rs 32-33 per kg.

📢 Express Explained is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@ieexplained) and stay updated with the latest

That, again, is the fallout of no institutional demand, whether from tea stalls and ice-cream makers or suppliers of khoa/chenna to sweetmeat sellers. In other words, it is a “shift” and not mere “movement” along the same demand curve.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05