- India

- International

Basu Chatterjee’s cinema celebrated the common man and woman with gentle humour

Along with the more popular Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Sai Paranjpye and Gulzar, Basu Chatterjee, who died today at 93, is often called the father of middle of the road cinema, a genre whose gifts include Chhoti Si Baat, Chitchor, Rajnigandha and Baton Baton Mein.

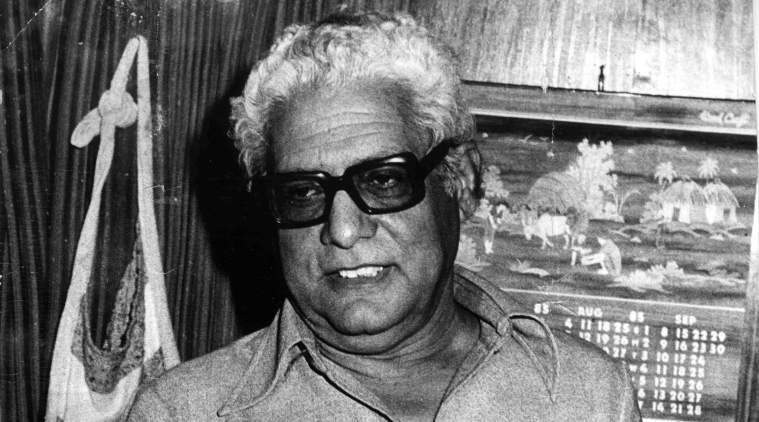

Film Director Basu Chatterjee passed away on June 4 at the age of 93. (Express archive photo)

Film Director Basu Chatterjee passed away on June 4 at the age of 93. (Express archive photo)

As rain lashes Mumbai, it’s exactly the monsoon weather which formed the backdrop for “Rimjhim gire sawan.” The hit Lata Mangeshkar version from Manzil (1979) featured a rain-drenched Amitabh Bachchan (a newly-minted superstar) and Moushumi Chatterjee romancing on the eerily-deserted Marine Drive, in what was then Bombay. No doubt, this is the song that many fans will play today, some to romanticise the Mumbai monsoon while a thousand others as a way of tribute to its director Basu Chatterjee who passed away on June 4 at the age of 93. Filmmaker Ashoke Pandit, who announced the movie legend’s death on Twitter, added that the last rites will be performed at the Santacruz cremation today at 2 pm.

Middle-class mascot

Basu Chatterjee was the man behind the 1970s fan favourites such as Rajnigandha, Chitchor, Chhoti Si Baat and Baton Baton Mein, all extraordinary everyday celluloid gems that looked at the lives of ordinary people, their ordinary problems, romances and dreams. In the 1980s, Chatterjee veered towards the more serious Ek Ruka Hua Faisla and Kamla Ki Maut, both starring Pankaj Kapur. While Ek Ruka Hua Faisla was a spin-off of Hollywood’s 12 Angry Men, Kamla Ki Maut (recently made available on streaming site Mubi) was a searing indictment of middle-class hypocrisy. All characters in it (with Pankaj Kapur, in older getup, playing father to two marriageable daughters) gladly indulge in needless tittle-tattle about a pregnant Kamla’s suicide, but they each have, at some point in their own lives, been prisoners of lust. The mother herself once tried to commit suicide by drowning but has successfully hidden that chequered aspect of her life from her husband and girls. Everybody has a past, but it’s easy to pin blame on the young Kamla.

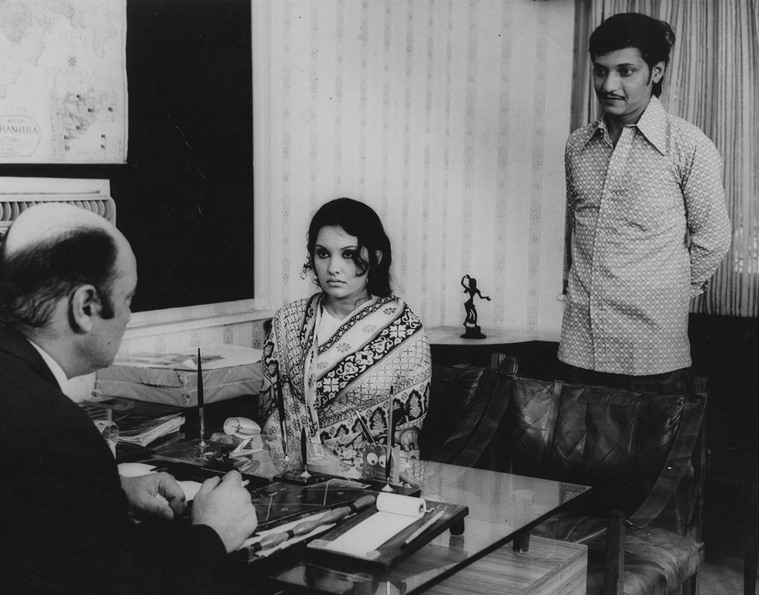

Vidya Sinha and Amol Palekar in Chhoti Si Baat. (Express archive photo)

Vidya Sinha and Amol Palekar in Chhoti Si Baat. (Express archive photo)

Inspired by Italian neo-realism, Basu Chatterjee was no stranger to social realism. Having learnt the filmmaking ropes under Basu Bhattacharya on Teesri Kasam (1966), he made his mark with the uncompromising Sara Akash in 1969. Influenced by literature (Sara Akash was based on Rajendra Yadav’s novel and even shot in his house), Chatterjee’s debut set a template for later films. Often, for his plots, he turned to books. The middle class became a strong subject because, as he once simply explained in an interview, “I am a middle-class person. My father was in the railways, and I myself travelled on trains and regularly commuted on busses. That’s the world I knew best and that’s what I sought to portray.”

Uncommon common man

In some of his most well-known hits from the ’70s, it was the ultimate simplicity of Amol Palekar that helped him relive his middle-class fantasies. Palekar was no Bachchan, but that was his sharpest suit (or a checked shirt, if you may). In these gentle comedies, Palekar played the common man, who gets into, at best, uncommon situations. In Chitchor, he falls for his boss’ (Vijayendra Ghatge) girl (Zarina Wahab). She innocently loves the poser — their young romance blooms under Yesudas’ soulful melodies — but her parents think it otherwise. The Barjatyas, who produced the film, tried a rehash with Hrithik Roshan, Abhishek Bachchan and Kareena Kapoor, but Main Prem Ki Diwani Hoon (2003) was a glorious debacle, failing to match the original’s magic. It’s hard to believe that Palekar, who excelled at shy and awkward characters usually messy at handling female attention, managed to pass muster as a larger-than-life dude with a frat-boy personality in Chitchor. Only when you equate his character with Hrithik Roshan’s in MPKDH that you realise what a relief Palekar was compared to Roshan’s relentless hamminess.

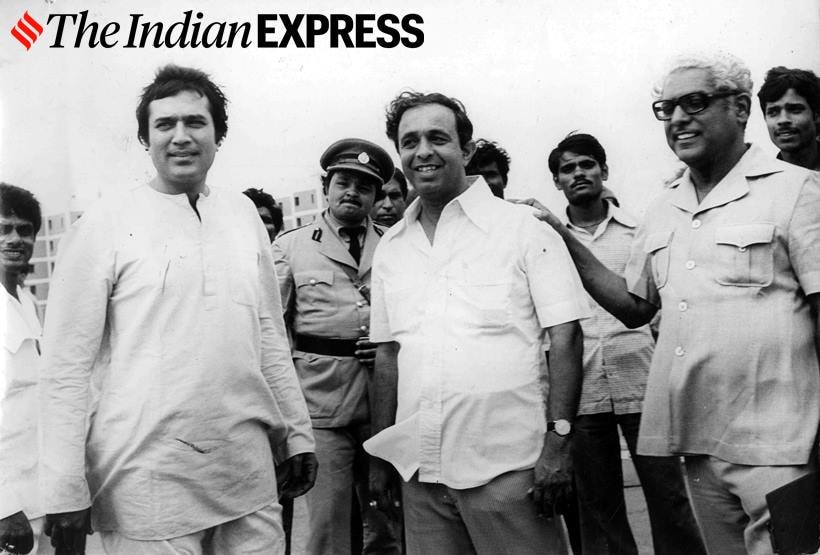

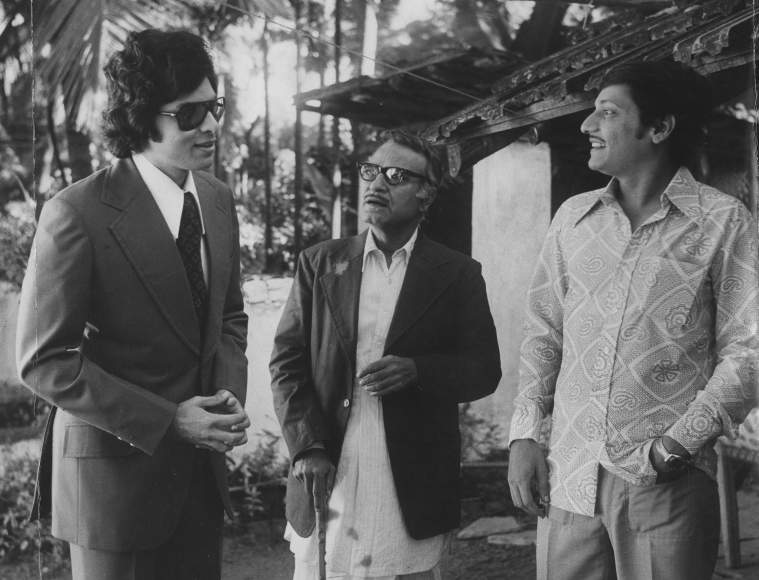

Rajesh Khanna, producer Yusuf Hassan and director Basu Chatterjee on the set of film Chakravyuha. (Express archive photo)

Rajesh Khanna, producer Yusuf Hassan and director Basu Chatterjee on the set of film Chakravyuha. (Express archive photo)

Lightness of touch

What, however, made Chitchor a success was Chatterjee’s lightness of touch. The same ability to locate humour in the everyday animated Chhoti Si Baat and Rajnigandha. Both featured the inimitable Amol Palekar-Vidya Sinha pairing. Sinha, in her simple but sophisticated saris, was the ideal pinup for the Palekar types, a dream-come-true catch if ever the Gods of Love are so kind to shine on him. Once again, Rajnigandha was based on a short story. It gave us, in the shape of Sinha’s Deepa, a woman of agency. Torn between two men, she even fantasises about her lovers in a song wondering whom to choose and whom to forget. The song in question (“Kaeen baar yunhi”) is sung by the great Mukesh, perhaps a unique instance in Hindi cinema when a male singer gives expression to a woman’s inner feelings. Most of these films had a brilliant soundtrack. While “Rimjhim gire sawan” is definitely a rainy-day ear-worm, Chatterjee’s output is replete with evergreen music, like “Rajnigandha phool tumhare”, “Kaeen baar yunhi”, “Chhoti si baat”, “Jaaneman jaaneman”, “Thoda hai thode ki zaroorat hai”, “Aaj se pehle aaj se zyada”, “Jab deep jale aana” and “Suniye kahiye kahiye suniye” among more.

Vijayendra, A. K. Hangal and Amol Palekar in Chitchor. (Express archive photo)

Vijayendra, A. K. Hangal and Amol Palekar in Chitchor. (Express archive photo)

Along with the more popular Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Gulzar and Sai Paranjpye, Chatterjee is often called the father of middle of the road cinema, a movement that combined elements of commercial and artistic schools — a sort of middle ground but groundbreaking in its own way. Filmfare magazine once called him, ‘The God of small films.’ Incidentally, Chatterjee’s films are often confused with Mukherjee’s perhaps due to their middle-class sensibilities, but to those entrenched in Hindi cinema’s idioms they can’t be more different, both having their own distinct styles. In 2016, Chatterjee told Filmfare that he’s proud of being compared to the beloved Hrishida: “I respect him. He was a valuable filmmaker. I found myself making his kind of films, though not consciously. One advantage that Hrishida had was he often remade his Bengali hits in Hindi whereas I used to pick subjects from literature.”

Also read | Basu Chatterjee gave us characters we felt for, we rooted for | Basu Chatterjee (1927-2020): A pictorial tribute to ace filmmaker | Celebrities mourn the demise of Basu Chatterjee | Why Basu Chatterjee’s interpretation of Byomkesh Bakshi is the gold standard

Besides his 40 odd films in Hindi and Bengali, the Ajmer-born director is also famous for his work on Indian TV, primarily the cult detective series Byomkesh Bakshi and the feminist Rajani starring the late Priya Tendulkar. The last great Chatterjee film was the madcap Chameli Ki Shaadi (1986), with Amrita Singh, Anil Kapoor, Pankaj Kapur and Amjad Khan cooking up a comic storm. Today, it has a cult following. A former political cartoonist with Blitz magazine (now you know where the humour comes from), Chatterjee retired only in the last decade but had continued to serve on award juries and film bodies. In a Rajya Sabha TV interview, asked to reflect on his illustrious career, he said matter-of-factly, “I made the films I believed in, some worked, others didn’t. Woh sab kashmakash chalta rehta hai (These ups and downs happen). But I am not unhappy.”

Click for more updates and latest Bollywood news along with Entertainment updates. Also get latest news and top headlines from India and around the world at The Indian Express.

Photos

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05