For many of us, coronavirus has inspired a bit of a germ obsession. We wash our hands until they’re chapped. We see other people as potential vectors. We wipe down our groceries with Lysol, apparently having decided that, if it comes to it, we’d rather die of disinfectant poisoning than a virus.

In our efforts not to contract Covid-19, many of us are getting a taste of a different kind of illness: obsessive-compulsive disorder. And for some who have spent years learning to cope with OCD, the latest crisis is undermining everything we’ve learned about our own brains.

I’ve been painfully aware of the threat posed by stray microscopic entities since I was a teenager, calling Planned Parenthood in a panic: could my girlfriend get pregnant from over-the-clothes stuff? But my fears extended well beyond questions of personal hygiene, and working to escape them has been a lifelong project.

At nine years old, I began feeling a compulsion to touch certain objects in my bedroom or on the playground at particular moments. I worried that if I did not perform these rituals, something horrible would happen, typically the death of someone I cared about – my parents; my sister; my hamster, Dave (not his real name). It was as if the chest of drawers or the swingset were on fire and the only way to put it out was if I personally touched them – which, looking back, seems kind of arrogant.

I was anxiety’s Chosen One, some kind of sad wizard incapable of making good things happen but burdened with preventing the bad.

As I got older, I learned to hide the rituals. Instead of needing to touch something, I might need to avoid wearing a certain shirt, or walking via a certain street, or listening to a certain song. As is the case for many people with OCD, numbers became a big issue: I got worried when the clock showed 42 minutes past the hour or a battery was 86% charged, and I had to repeat various movements five times (a mere two repetitions could harm my dad; four could be fatal to my orthodontist).

Sometimes I believed – well, didn’t really believe, but feared – that the world was giving me signs in the form of the tiniest unexplained occurrences at home: for instance, if a CD was skipping it meant listening to the album was dangerous. A missing fork or knife could mean I’d failed to perform a needed ritual in the kitchen.

All this magical thinking was a manifestation of the disorder that seems not to have entered the popular consciousness: when someone says “I’m so OCD”, they usually mean they are obsessively neat, not that they avoid listening to the pop-punk of Blink-182 out of fear for their family’s safety. (In the interest of debunking stereotypes, I should point out that I have OCD and also manage to maintain a very messy home. Hygiene is an issue; tidiness hardly enters the picture.)

I knew it was nuts, which, according to one child psychologist (he was an adult – I was the child), was what made me merely neurotic and not psychotic. It was a small comfort. But it was the key to tackling the issue.

In my 20s, I began cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). It typically treats OCD through a process called exposure and response prevention (ERP), in which you deliberately expose yourself to situations that trigger discomfort, then avoid performing whatever ritual is supposedly required. My therapist and I created a list of feared situations and my ritualistic responses, ranked by how much anxiety it would cause me to skip each one. Then I worked my way through them, from the least stressful – along the lines of wearing a forbidden shirt – to the most, which involved exposing myself to a supposedly germ-ridden environment, then neglecting to wash my hands.

So I sat in my therapist’s office listening to a tinny rendition of Nick Drake’s Pink Moon through my phone, set on the arm of the sofa. I had avoided the song for years because I was sure the lush strumming could send my sister to her doom – perhaps because the lyrics hint at a mysterious omen. (She joked about her epitaph: “Here lies Matt’s sister. He downloaded the wrong song.”) At the time, she happened to be on a plane, heightening my fears. As the music played, my anxiety soared. But with each listen, it got a little easier, until it provoked hardly any concern – with the added bonus that her plane remained aloft. I performed similar routines for every ritual on my list, and to my surprise and delight, I felt like I was detoxifying my brain.

It worked, and it held for years. But coronavirus has shaken the foundations of what I built. Suddenly, the vague threats I have always perceived are not imaginary but specific and real. There are dangerous germs everywhere, and it threatens to undercut the very techniques that people like me have used to escape the OCD monster.

What happens when constant hand-washing is actually recommended, when friends are quarantining their groceries for 72 hours, when the most practical people you know have taped-off contamination “hot zones” in their homes next to arsenals of hand sanitizer? The line between the rational and irrational – once clear even as I performed bizarre rituals – risks becoming blurred.

And it is not just questions of hygiene that become magnified. Anxiety, as another therapist (I’ve racked up a few) wisely told me, is a means of trying to control things. When your parents, whose age puts them in a higher-risk group, are across the country, it’s pretty hard to control their environment beyond panicked daily emails: are you leaving the rubbing alcohol in place for at least 30 seconds? Have you checked your feet for any redness since this morning? What if the cat has coronavirus but he’s keeping it private? Thus the magical thinking re-emerges: perhaps I can avert disaster from afar by avoiding that blue T-shirt.

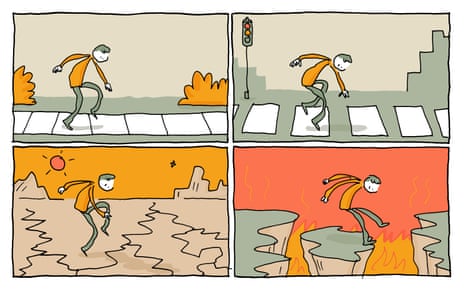

The result is tiptoeing through life, with the smallest decisions – what to have for breakfast, which words to write in this sentence – sparking a sense of discomfort that indicates looming tragedy. If even one person believes that a butterfly beating its wings can affect events thousands of miles away – if there is an infinitesimal chance I could be saving a life – how can I justify not doing the rituals?

At the core of exposure and response prevention therapy is the acceptance that, in fact, no one can be sure of the truth. Instead of trying to convince oneself that the rituals have no real-world impact, ERP – and the broader medical profession – calls for tolerating uncertainty. You’re not telling yourself: “It won’t hurt anyone if I wear the blue shirt.” Instead, you’re saying: “Maybe it will hurt someone – I can’t know. But I’ll do it anyway.” Given the obsessive-compulsive person’s mindset, this might seem like brutal behavior, akin to shooting a gun blindfolded and hoping it doesn’t hit anyone.

But in the past, it has worked for me, either because I am at heart a callous would-be murderer or because on some level, I know that the worst damage the blue shirt can do is make me look like a dweeb. Accepting uncertainty is something we do every day, often with little thought: we could be hit by a car or fall down the stairs. But instead of being paralyzed, we just look both ways or hold the bannister.

I can’t speak for everyone with OCD, but I hope this might be of some help to others during the pandemic: for me, the solution lies in adjusting the placement of that line between irrational and rational, just as everyone else is doing right now – and then trusting that part of you that, deep down, can still recognize the distinction.

Discussing some weird behavior, my therapist once simply asked: “Does it feel like a ritual?” It’s something I keep asking now, and even in a pandemic, it works if I let myself believe it. Some activities that once felt like OCD – for instance, wiping down doorknobs – no longer do, probably because knowledgeable people have suggested doing it. Cleaning my shoes on returning from a walk around the block or bleaching an area I disinfected minutes earlier, however, continue to feel beyond the bounds of rationality. I still struggle with these decisions every day, but it’s a start.

My hope is that the pandemic will offer people without obsessive-compulsive disorder – NoCDers, I call you folks – a better understanding of what it is like to feel that the tiniest of actions can have earth-shattering consequences. OCD is a spectrum, and we have all probably brushed up against the edge at some point. On the bright side, as long as the illness continues, we are all gaining valuable practice living with uncertainty.