By the time 20 Indian soldiers had died and a still-unknown number o f Chinese soldiers faced casualties after a high-altitude melee in the normally obscure Galwan Valley on June 15, India and China were already well into a border crisis. The events of June 15 simply had the effect of sharply raising the profile of this latest Himalayan dispute between Asia’s two giants; they marked the most serious violence between them since 1967 and the first fatalities along this border since 1975. As facts-on-the-ground have quickly changed in this treacherous Himalayan terrain, what the world may be witnessing is nothing short of a fundamental redefinition of the nature of Sino-Indian border disputes—and the broader relationship between these two Asian powers.

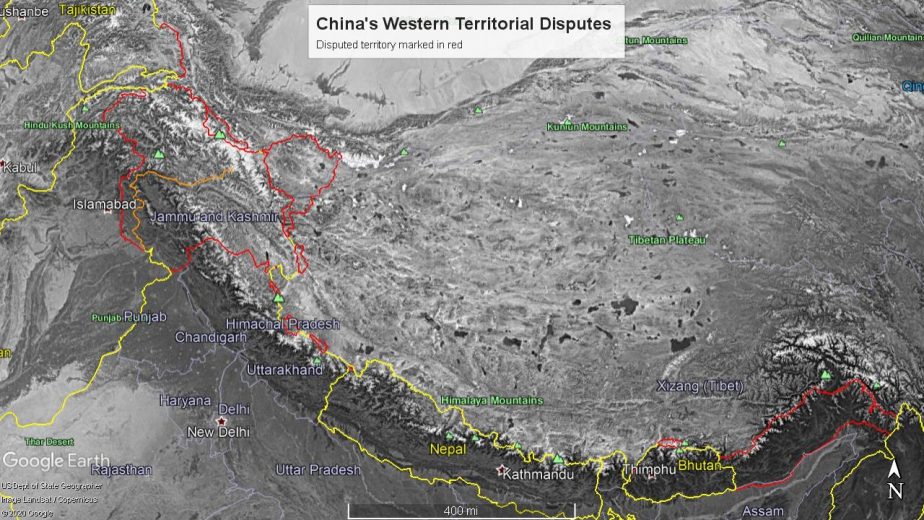

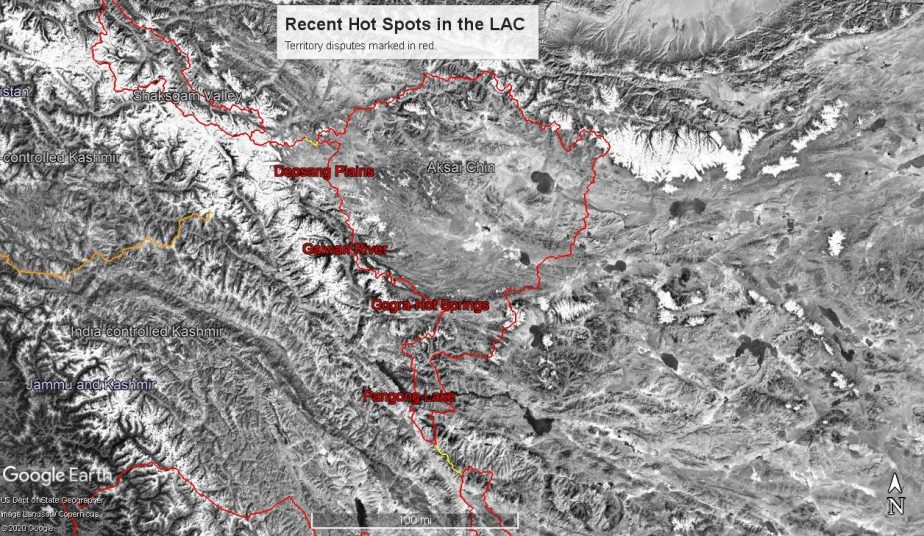

Starting on May 5, troops from both countries entered tense standoffs at multiple points along their border. These standoffs took place both along the undefined, un-delineated, and un-demarcated Line of Actual Control (LAC) and along part of the settled international border between the two countries, between the Indian state of Sikkim and China’s Tibet Autonomous Region. In Eastern Ladakh in recent weeks, the core points of contention have included the Galwan Valley, Pangong Tso (Lake), the Gogra-Hot Springs area in the Chang Chenmo River valley, and the Depsang Plains. Around 1,200 kilometers away, a separate standoff had taken place at Sikkim’s Naku La Pass, along the supposedly settled Sino-Indian border there.

The Fait Accompli

Through the ongoing standoff, both sides have buttressed their positions by moving in additional personnel and equipment—developments that have been well-catalogued by open source geospatial analysis. While the two sides have somewhat successfully used existing military and diplomatic channels, established over years of careful, quiet diplomacy, to manage their differences, they’ve been unable to successfully “disengage,” despite an initial June 6 agreement through military channels. A July 6 call between Ajit Doval, the Indian National Security Advisor and special representative for border issues, and Wang Yi, China’s State Councilor, Foreign Minister, and counterpart special representative, has resulted in an encouraging new commitment to disengage—with apparent follow-up steps by both sides reported. It may, however, be still too early to assess the effectiveness of the Doval-Wang call. Indeed, the June 15 skirmish broke out in the course of implementing the disengagement that they’d agreed to and there’s potential for much to go wrong still.

The strategic picture in the western sector of the LAC—Galwan River, Pangong Lake, Gogra-Hot Springs, and Depsang Plains—remains largely negative for India. Chinese People’s Liberation Army positions have expanded to unprecedented levels since the 1962 war between the two countries. At Pangong Lake, the Chinese side is in the process of setting up a helipad on territory that India perceives to be its own, in addition to substantially increasing its personnel counts to unprecedented levels in recent times. At a strategic river bend on the Galwan River, known to the Indian Army as “y-nalla” for its resemblance to a y-shaped bend in the valley, Chinese troops have set up a major encampment—also on territory India perceives to be its own. The July 6 Doval-Wang call has resulted in a disengagement from this area, but the tenability of these steps remain uncertain.

Together, recent developments underscore the fundamental shift in the pre-May 2020 status quo along the LAC and expose why the very phrase “line of actual control”—codified out of the post-1962 ceasefire line in the Sino-Indian 1993 Agreement of Peace and Tranquility on the Line of Actual Control (PDF)—obscures more than it specifies in understanding the situation especially in Eastern Ladakh. Without definition, delineation, or demarcation, the “line” is anything but, with at least 23 major areas (including Pangong Lake, most prominently) where Indian and Chinese perceptions of the line diverge significantly. Instead, what’s underway today is a redefinition of the pre-May 2020 status quo by way of changing the nature of “actual control” of this high-altitude territory.

Over years of Sino-Indian border talks, the Chinese side appeared to intentionally have an interest in preserving a degree of ambiguity about the line. Older Chinese maps dating back to the 1960s showcase differing claim lines from portrayals of the LAC on Indian maps, or maps widely made available today (including by online mapping services like Google and Bing Maps). In one account of a 2002 encounter between senior Indian and Chinese diplomats to discuss the LAC, the head of the Chinese delegation refused to accept an Indian map portraying New Delhi’s perception of the LAC (in delineated form). Shivshankar Menon, a former Indian foreign secretary, confirms this telling, noting that over the course of such exchanges in the early 2000s, the Chinese side refused to “go on with this exercise“ and “used several reasons” to justify their position. Menon concluded that “they didn’t want to have to commit themselves to respect a line.” And so the ambiguous status quo persisted in Eastern Ladakh, with the reality of control being determined through customary means, including patrolling routes used by Indian and Chinese military personnel over territory claimed by both simultaneously.

The Chinese fait accompli in Eastern Ladakh has been both decisive and coercive, leaving few measures short of military escalation for India to find a way back to the status quo ante. Even if the July 6 disengagement at Galwan creates results in the short-term, the final outcome along the LAC may largely still prove more advantageous to China. Meanwhile, background political factors have become considerably more complicated since the June 15 skirmish propelled the ongoing standoffs at the LAC to national prominence in India. An undeniable surge in Indian nationalism as a result of the June 15 violence complicates the Indian government’s ability to work quietly toward a diplomatic off-ramp with Beijing. As a result, the Indian government has sought to retaliate asymmetrically toward China, for instance, by cracking down on 59 Chinese-made apps and reviewing foreign direct investment rules specifically for Chinese firms.

The End of the Old Diplomatic Normal

The severity of the ongoing standoff has appeared to end the post-1993 Sino-Indian “normal” along the border. In diplomatic terms, the list of achievements between the two sides is not particularly short. For instance, in 1996 their Agreement on Confidence Building Measures in the Military Field (PDF) codified the conventional arms control measures that explained one of the core curiosities of the June 15 encounter: why it was a fist-fight. That agreement saw both sides agreement to disarm their troops of ammunition-imbued small arms within 2 kilometers of the LAC.

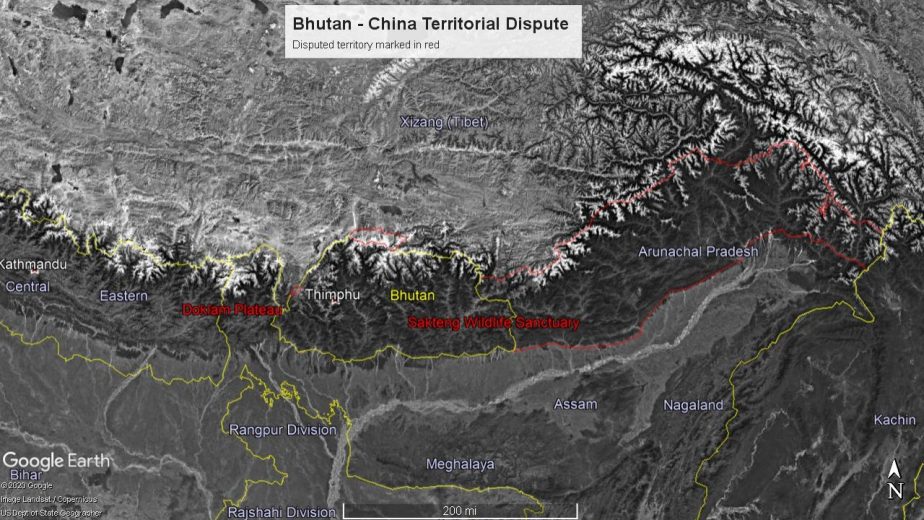

Later, in April 2005, the Agreement on Settlement of the Boundary Question (PDF) sealed the Sino-Indian border in the Sikkim-Tibet sector. A 2012 bilateral understanding addressed a lingering uncertainty in the Sikkim sector concerning the China-India-Bhutan tri-boundary point. The 2017 Doklam standoff, whereby Indian troops caught the PLA off-guard by cross India’s international border with Bhutan to enter a standoff on non-Indian territory, stressed the 2005 and 2012 understandings—contributing perhaps to this year’s escalation. In 2013, the two sides concluded their last major border-related agreement: the Border Defense Cooperation Agreement (PDF), which codified procedures to manage border-related disputes and incidents.

A complicating background factor since 2013 concerns domestic political changes in both India and China and the ways in which they’ve fed into the management of foreign affairs along their peripheries. Since that year, China under Xi Jinping’s leadership has pursued increasingly more assertive policies along its maritime and land-based peripheries. In 2014, Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party won power and were reelected with an overwhelming mandate last year. The Modi government sought to make an increasingly more assertive approach to India’s periphery—particularly concerning Pakistan—a centerpiece of its national security approach. In September 2016 and February 2019, India’s armed forces conducted major operations against Pakistan-held territory—across the international border in the case of the latter—underscoring this new approach and raising questions about whether India had abandoned the “strategic restraint” that, most notably, saw it take no significant military actions against Pakistan after the November 2008 terror attacks against civilians in Mumbai by Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorists who had well-documented ties to Pakistan’s intelligence services.

While Sino-Indian border tensions simmered during these years, they did not spill over into anything like the ongoing standoff. The closest was the 2017 Doklam standoff , which ended with a successful August 2017 “disengagement” whereby Indian troops left territory disputed between Bhutan and China. (Apart from India, Bhutan is China’s only other land neighbor where an unsettled border remains.) After the disengagement, however, the PLA significantly buttressed its position at Doklam, effectively changing the status quo in its favor over the long-term. Chinese incursions in 2013 south of the Indian Army’s Daulat Beg Oldie base and in 2014 in Chumar (during a summit between Xi and Modi in India) were amicably deescalated.

Among these recent standoffs, Doklam was without doubt the most serious and novel in nature. Most notably, the eponymous territory—the Doklam Plateau—is not disputed between India and China, but between China and Bhutan. At the onset of the standoff, Indian armed forces crossed what they recognized to be an international border between India and Bhutan to stop the People’s Liberation Army from constructing a motorable road that could have been extended southward toward Indian territory. The step by the Indian Army to cross the boundary to physically impede construction of the road, by some accounts, caught the PLA off-guard and prompted a broader reassessment in China of India’s border policy. In the Chinese view, the Indian reaction to Doklam may have indicated a change in status quo conditions in the Sino-Indian borderlands—at least in terms of the risks the Indian side was willing to take to prevent unilateral Chinese steps to make infrastructure improvements.

New Background Factors

Two other important factors have stressed the “old” normal. First, as many commentators on the ongoing dispute have noted, Indian infrastructure improvements in proximity of the LAC in Eastern Ladakh may have sparked this year’s standoffs. In particular, New Delhi’s improvements to the so-called Darbuk-Shyok-Daulet Beg Oldie (or DSDBO) road, which runs somewhat parallel to the LAC in the area, could have been perceived by China as granting New Delhi an unacceptably large military advantage in the region—in way similar to Indian feelings about Chinese road construction in Doklam. The construction of these types of roads has been a long-running endeavor for India and dates back to a 2005 policy change prioritizing the improvement of road networks along the LAC. Even as China’s aggregate military power eclipses India’s, Indian forces have more experience and relative capability along the Himalaya, making these roads a potential force multiplier in a conflict by facilitating more efficient logistics and resupply for what is otherwise deeply difficult terrain for the conduct of sustained military operations. As a result, Beijing may have taken an announcement this January by India’s Border Roads Organization that 11 new strategic roads along the LAC were nearing completion as a warning.

The second background factor that may have been interpreted by China as yet another change to the status quo by India pertains to New Delhi’s decision in August 2019 to change the administrative status of Ladakh to a union territory through the bifurcation of the erstwhile Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. The practical effect of this decision was to grant New Delhi direct control of the region’s political affairs. China has some experience with this sort of a step—what the Carnegie Endowment’s Ashley Tellis has called “cartographic aggression”—to assert sovereignty over disputed regions. In 2012, amid a major standoff with the Philippines over Scarborough Shoal, China announced the creation of Sansha City, a prefecture-level city in Hainan province encompassing most of the disputed waters in the South China Sea. Earlier this year, it created two new districts in Sansha, too. Despite the similarities with India’s August 2019 decision, China reacted sharply and negatively to India’s decision. A day after Indian Home Minister Amit Shah presented the Modi government’s bifurcation plan, the Chinese Foreign Ministry put out a statement noting that “India has continued to undermine China’s territorial sovereignty by unilaterally changing its domestic law.”

With the fraying of the old diplomatic normal and the emergence of new background factors, the amicable settlement of border disputes appears to have become more challenging for the two countries.

First, despite maintaining almost total official silence through the end of May, China—through official foreign ministry spokespeople, diplomatic envoys, and authoritative and nonauthoritative state media—has been especially vocal about the nature of its specific claims in the disputed areas. After the June 15 clash, for instance, Beijing began to assert total sovereignty over the entirety of the Galwan Valley. This appeared to be materially new in June 2020: “Galwan” makes no appearances on the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ website prior to this month.

That this effectively dormant claim has now reappeared suggests a new ambit to Chinese activities along the border. Separately, in recent weeks, China has introduced a similar dormant claim to a piece of Bhutanese territory. China and Bhutan do not have formal diplomatic ties, but have held 24 rounds of talks to settle their disputed border. Bhutan has the distinction of being the sole country, apart from India, to have a still-unsettled border with China. This new Chinese claim would, in effect, bring another highly coveted piece of India-administered, China-claimed territory in Arunachal Pradesh into reach. But the Bhutanese government has reacted sharply to what is effectively a brand new claim to some 11 percent of its territory.

Second, in the India-China context, while the mechanisms established between 1993 and 2013 continue to play a part in allowing for institutionalized exchange at the military and diplomatic levels, it is less clear that they are functioning to effectively deescalate tensions. Most critically, the rate at which both sides have functionally increased their military presence along the LAC while talking suggests that whatever bargaining is taking place through these means is largely window-dressing for a much more serious fraying of the “old normal.”

This view appears to be have takers on the Indian side. Former Indian Ambassador to China Gautam Bambawale (now retired) commented after the June 15 clash that the “entire architecture has collapsed, and is now in the heap of history.” Former Indian Foreign Secretary Shivshankar Menon noted that China’s force build “casts into question China’s commitment to the (existing) agreements.” The special representatives channel—that between Doval and Wang—appears to have borne fruit, but the broader picture along the border still bodes poorly for overall stability. For instance, a closer read of the Chinese and Indian readouts of the discussions between the Chinese readout of the Doval-Wang call and the Indian readout suggests considerable daylight between the interpretations of the situation on the ground by Beijing and New Delhi. For instance, it’s unclear what exactly each side means in its public use of the word “disengagement” and what precisely is to be implemented on the ground in areas like Galwan and Pangong Lake. According to anonymously sourced Indian reports, an element of verification does appear to be at work, however.

An Opening For Settlement?

There’s normally a seasonality to Sino-Indian border skirmishes. Given the high-altitude venue for these disagreements and melees, the spring and summer generally are the times favored for revisionist action. The ongoing mode of operation along the LAC for both sides—asserting sovereignty through a physical military presence—quickly becomes unfeasible once the brutal Himalayan winter sets in. There are precedents for standoffs lasting through bitter winters. In this way, the ongoing standoff may come to resemble the Sumdurong Chu skirmishes, which began in 1986 and hung the prospect of a Sino-Indian war over the two countries until an effectively thaw could be realized two years later when Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited Beijing. The total resolution of the underlying factors in that skirmish took even longer.

The 2020 Sino-Indian standoff will have significant effects on the broader relationship between these two countries. For instance, a generation of Indians will likely come to perceive China as more than an adversary, but as an enemy—perhaps only second to Pakistan. The mere fact that 20 Indian soldiers died at Chinese hands has enflamed passions which, in a democracy like India, come to constrain policymaker options. Meanwhile, gruesome details of the June 15 encounter continue to emerge, making Chinese aspirations for a return to the old diplomatic normal more difficult.

For Indian policymakers, there are already hard lessons that have been learned. The greatest among these is that the fait accompli, by its very nature, is best prevented rather than reversed. The task at hand for Modi and his advisors today is to find a way to put the PLA—and its tents, its uniformed soldiers, its intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets, and its artillery guns—as far back from the LAC as possible. But once the PLA has dug in, as it already has, it becomes more difficult to attain a permanent return to the “old” normal, where uncomfortable gaps in both sides’ divergent understandings of the LAC could be glossed over because patrols were sparse and unspoken understandings prevailed.

Paradoxically, however, 2020’s developments may lead to more fertile ground for a final settlement of the Sino-Indian border—even if this settlement is unlikely to be on terms considered favorable by the Indian side. Assuming that the June 2020 status quo is unlikely to be reversed to that of April 2020, the reduced ambiguity between what each side claims and controls could provide an important opening to move toward an exchange of official maps, culminating in the eventual delineation and demarcation of a final border.

As distasteful as this might be to India, there are potential advantages. First, the Sino-Indian border does not only encompass Eastern Ladakh and Sikkim, but also extends to the eastern sector, where the Indian-held and administered state of Arunachal Pradesh is claimed in its entirety by China. As the recent Chinese claim to a new piece of Bhutanese territory previously unclaimed in official Sino-Bhutanese border negotiations talks suggests, Beijing remains intent on pressuring India in the east as well. If present-day administrative realities are likely to form the basis for a final, comprehensive solution—whereby China retains control of Aksai Chin (west of the LAC in Ladakh) and India retains control of Arunachal Pradesh—then India should be compelled to treat the dramatic changes to the status quo in Eastern Ladakh as an urgent reminder that now is better than later. Historically, China has treated the comprehensive settlement of the border with little urgency, likely with the understanding that its ability to project power and sustain a military presence along the LAC will only grow to India’s disadvantage in the years to come. The 2020 standoff is, in many ways, an acute demonstration of this. The lower-hanging fruit—a successfully implemented “disengagement” along parts of the border and an irreversibly retrenched forward position for the PLA elsewhere—will likely only set the two countries up for more inevitable clashes. If India can’t reverse today’s fait accompli, it should use all tools at its disposal to prevent the ones yet to come.

Ankit Panda is senior editor at The Diplomat and director of research at Diplomat Risk Intelligence. He writes extensively on security and geopolitics in the Asia-Pacific region. Follow him on Twitter at @nktpnd.

This article was published originally at Datayo, an open source platform to identify, track, understand and address emerging threats to humanity. It is republished here with kind permission.