- India

- International

How song and dance made love and desire visible on screen

Writer and filmmaker Paromita Vohra on Saroj Khan’s role in bridging different styles and eras of Hindi film dance

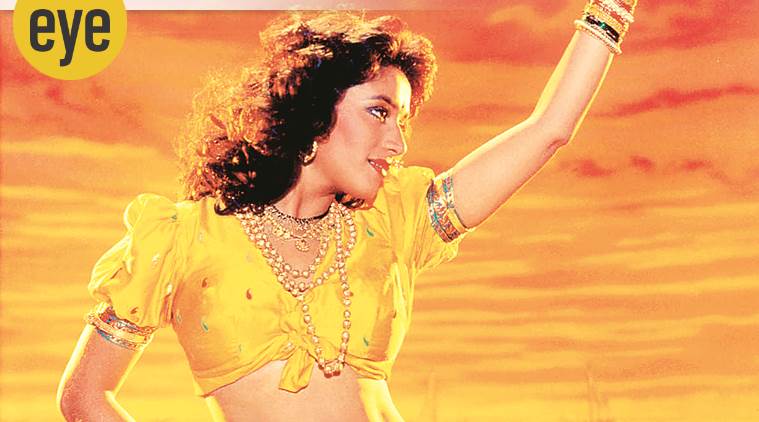

Madhuri Dixit in Sailaab (1990)

Madhuri Dixit in Sailaab (1990)

The long and illustrious tradition of song-and-dance in Hindi cinema is increasingly seen as an unnecessary appendage, needed for marketing a film but to be finally parked in the end credits. But what do we lose when we cut ourselves off from it? In an essay in tiltpauseshift: Dance Ecologies in India (Gati Dance Forum, 2016), writer and filmmaker Paromita Vohra makes a case for Bollywood dance as a unique “symbolic language” and a way to simultaneously accommodate hybrid, even transgressive, ideas of pleasure, desire and sexuality. Vohra’s work as a filmmaker, writer and feminist, celebrates and articulates the queerness and non-hierarchical in Indian visual and pop cultures. In this interview, she speaks on how Saroj Khan took the song-and-dance aesthetic further, and why its dismissal is a part of a growing masculinisation of Indian culture. Excerpts:

In what way is the song and dance in Hindi films an art form?

The song and dance in Hindi films is a unique cinematic object. It is the poetic made visible on film, the tangible rendition of our emotions.

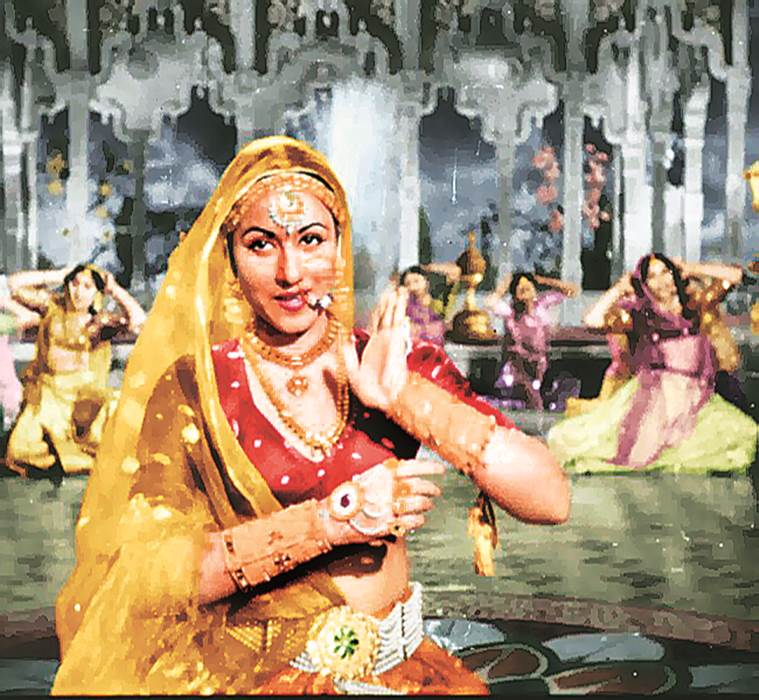

Each song and dance is a coming together of many aesthetic and personal histories, of myriad dance, theatrical and musical forms. And so, it becomes a complex and contemporaneous way of understanding South Asian history, the emotional meanings of history. One of my favourite songs is Mere piya gaye Rangoon (1949). It was written by Rajendra Krishan, composed by C. Ramachandra, sung by Shamshad Begum, who came from a conservative Muslim family. It’s said her father permitted her to sing on condition that she would record in a burqa. She pronounced telephone as telephooon. And it became a big rage. Rajendra Krishan, a poet from Punjab, wrote songs that featured metaphors of post office (aankhon ka daak khana, nazron ke taar hain), telephone, and such modern experiences of the time. In this manner, Hindi film music synthesised the new and what seemed to be declining to mirror contemporary experiences.

Social dramas, dealing with personal conflicts, often expressed the interiority of the individual through song. The private worlds of emotion, lovers’ interactions, the interaction between parents and children, and the other shifting relationships of the time were expressed through song. Why were there so many songs about teachers and children at a certain time? Think of Nanhe munhe bachhe (1954), Aao bachho tumhe dikhaye jhanki Hindustan ki (1954) and others. They were being made at a time when education of the masses was seen as an entry point to the new democratic nation.

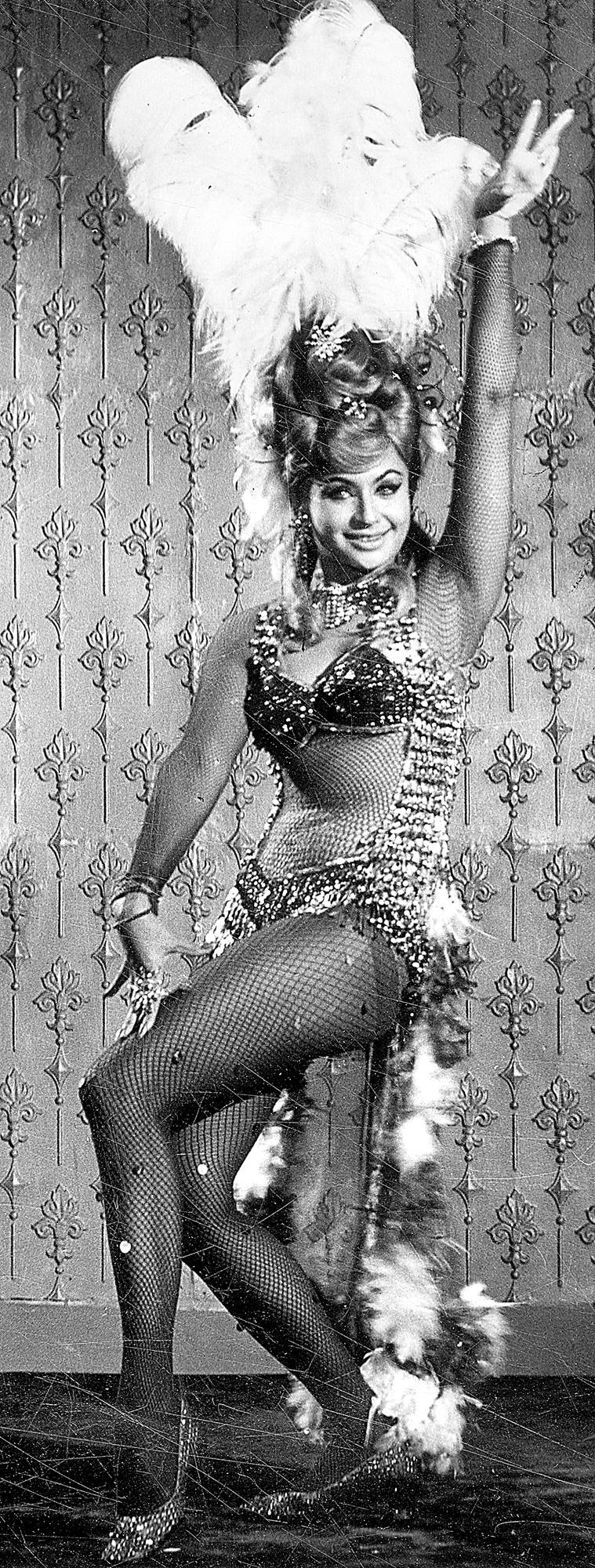

Varied styles of music and dance could sometimes be found in one film — a mujrah, the twist, a sad song, a picnic song, a piano song — a sad picnic song (Jab chali thandi hawa) etc. That meant, as a cinema practitioner you had to learn to discern many aesthetic languages and to be open to heterogeneity and aesthetic variety, as well as be aware of your own language. All these feelings, styles, worlds, sensibilities are accommodated in the film. Every facet of desire is simultaneously present too – objectification, pining, overtures, poetic expression – only one thing does not represent the entire world of desire.

What relationship did the song and dance have to older forms?

Many dancers, musicians, song-workers came from the cultural complex of courtesanal and traditional forms that were a part of the older bazaar culture into films. They were neither respectable nor non-respectable, and marked by some degree of female autonomy and non-normative sexual expression of various kinds, as many scholars have shown. Colonialism saw them as ‘dirty’ or inferior aspects of Indian culture. In response, a more high-minded aesthetic emerged, dedicated to higher causes of philosophy, spirituality, nation, politics, reform – which has formed the basis of our secular elite culture.

Actor Helen in a cabaret number. (Express Archive Photo)

Actor Helen in a cabaret number. (Express Archive Photo)

Many artists came from worlds and economies which had gone into decline, transitioned to theatre and then to film, bringing their forms, traditions and skills along, and joining these with others (like Christian musicians trained in Western music). Some of these were earlier consumed only by elites, but recording and films meant they reached a wider and diverse audience, and audience and performance changed each other.

How do you see Saroj Khan fit into this?

Saroj Khan didn’t come from a family of traditional performers. She came from a very poor post-Partition family and began working at 3 years old. She was a background dancer in Aaiye meherbaan at around 10. She assisted Sohanlal but also worked with a whole range of artists, and choreographed about 3000 songs. You could say she is educated in a school of cinematic dance, which remixed diverse styles and traditions. But because her career spanned such a large arc of time, in a way she bridges many worlds, and she carries the memory of these worlds in her body and dance style.

She had a uniquely cinematic dance vocabulary, which is very emotional, but also very physical. Her dance combines the soulful quality of the earlier dance with a very visibly articulated physicality. She became very prominent when popular culture moved from audio to visual, from radio to television. In ‘Humko Aaj Kal Hai Intezaar‘ (Sailaab, 1990), for instance, you see how pronounced every movement is, how it is so visualized and amplified by the camera movement. She created a very extruded version of dance forms, which were very soulful and sensual – but also structured with hook steps.

In one interview, she says that she doesn’t listen to the script. She listens to the words of a song and creates the dance.

It’s important to remember that Indian choreographers don’t only create the dance movement – they direct the picturisation and shot-taking too. The older name of “dance director” feels more accurate. Saroj Khan restored this work to professional importance by compelling Filmfare to institute an award for choreography, and we may now know dances by choreographer, not only by performer.

Paromita Vohra. (Photo by Oni Sen)

Paromita Vohra. (Photo by Oni Sen)

Why do you think that the song and dance is seen as a falling short on the path to modernity?

One answer is self-hate. These are all postcolonial convulsions in a way. When I was growing up, you didn’t admit to watching Hindi films, it is something that you told your friend in secret. There is a feeling that when you go out in the world, you have to be English-speaking. And it goes hand in hand with the idea of being a secular Indian, who has no identity marks. She has an accent which is what we call convent-educated but which is scrubbed of her mother-tongue inflections. It’s ok if it’s tehzeebi high culture. If middle-class people carry their regional identity with them, then they are not ‘modern’. So you edit and constrain your regional self, your emotional self, and then there’s the discomfort with pleasure for itself, and how it elicits an unbridled response from us.

But while song and dance is an important aesthetic, it had become formulaic in the 1980s. There had been another aesthetic, growing through the parallel cinema movement and the oncoming realism styles of filmmakers like Ram Gopal Varma and Vidhu Vinod Chopra. There was a desire to make a different kind of film, set apart from the existing Bollywood tradition. Some of it is fabulous also. But after a while, it became a hierarchy – where realism is more rational, more political, hence better – and now, it is the formula, to create a ‘globally’ acceptable version of Indian-ness in cinema.

Every single interview I ever read in the early part of this century had a filmmaker (or critic) saying, “This is a good film without the usual song and dance.” But, even so, in order to promote a film, you need a song. So lip-sync songs have now become removed from the film, except as item numbers, not central to the emotions of the film.

I think Sanjay Leela Bhansali is one practitioner of that Hindi film aesthetic. Melodrama, operatic, spectacular. Very emotional. Saroj Khan was also fluent in that aesthetic. She is saying “Mujhe gaana batao. I don’t care baaki film mein kya ho raha hai”. I am the auteur of the song. In a sense, one film accommodates many artistic voices, not that one (usually male) auteur notion. Our inability to recognise that this is one aesthetic and realism is also just another aesthetic, an artifice of filmmaking, pushes us towards homogeneity and the current fashion where films are critiqued on the basis of a woke toolkit. “This is about issues that are important, so that is good.” The world of emotion – less neat and politically correct – becomes too vulgar, too contradictory, too unsanitary, and is ironed into flatness.

But, if we keep aside this critique, how do we as viewers consume these films? In your essay, you write,“a kind of bodily contact happened between the cinema figure and audience, which altered the bodily experience of the viewer when outside the cinema hall. The cinema hall was in that sense a transgressive physical experience where one took in diverse bodies into one’s own and remixed them with one’s own physical language, reframing respectable bodies and mobility within and via the body.”

In the darkness of the theatre, you become one with cinema. Many things which are forbidden are allowed inside. The person you can’t fall in love with, the romance you can’t have, the queerness you can’t reveal. All of those things find a release. Either that release manages your desire, or it increases your desire, fantasy makes “reality” or the norm unacceptable to you.

Now, we have a low-contact experience of the movies and also a segmented one – women’s films, superior realistic films, ironic kitsch, queer-themed. It keeps realities more separate, even while making some more visible. You ritualistically enact an identity while watching films, rather than experience the catharsis of art and emotional storytelling. A mammoth identity machine functions in cinema, news, Twitter and everything becomes coordinated.

Actor Madhubala in Mughal-e-Azam. (Express Archive Photo)

Actor Madhubala in Mughal-e-Azam. (Express Archive Photo)

It’s like gentrification. Then the untidiness of emotion, behaviour and choice in films, exemplified by hard-to-categorise song and dance, has to relocate. It doesn’t disappear, because that’s life. And I would say that’s what happened with Saroj Khan. She brought back something that had gone away. Then she got out of fashion. But that thing is there na? In the TikTok dancing, the melodrama of old Bollywood in these videos. But instead of being present all over the place, it is sectioned off in one place.

This distrust of emotion is reflected in other ways. For instance, a young man once told me that the most tiring thing about dating is the effort not to fall in love. If you ‘get’ emotional, you are a fool. Emotions are not efficient, in a growing masculinization of the culture, even as we talk more of gender.

I think we miss that emotional nourishment in popular culture, which is more and more propagandist, and that is why we are always feeding off each other in public conversation. Offence or anger are the emotions we validate easily.

Someone once said that Hindi film music gives us a soundtrack to our lives. What does dance in Hindi films represent to us?

It gives us sex and body, in all its different formats and expressions. Our physicality is continuously minimised and judged — are you fair enough? Thin enough? Pretty enough? But when you are dancing, you are in a non-verbal space and expanding meanings of the body’s attractiveness. You are in a liminal physical space. It is neither sex, nor exercise – not purposeful in a way. It is there for the body alone, but reminds that mind, love, emotion — nothing is outside the body. It consolidates these aspects that society keeps fragmenting and cordoning off from each other. It helps us be rapt in ourselves.

I have seen videos of transwomen and cis-men dancing to multi-gendered Bollywood songs on the internet, and people comment with pleasure not nastiness. It’s like, while watching dance or dancing, we acknowledge that all queerness, all expressions of self are also valid.

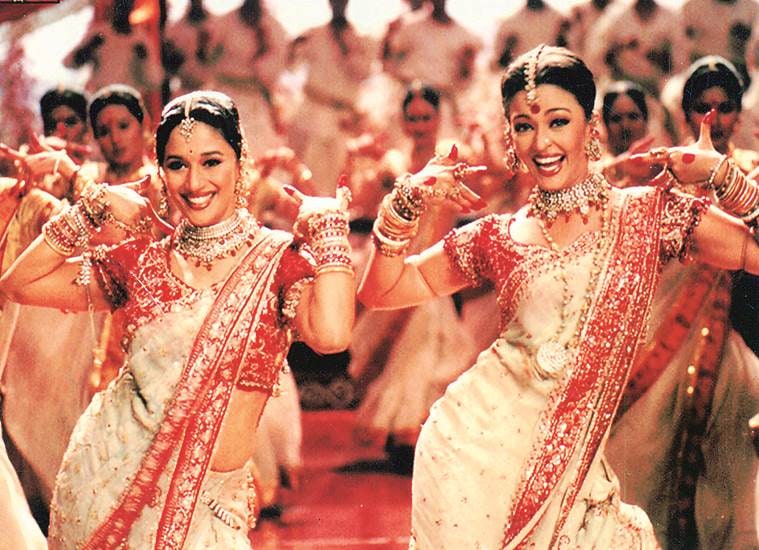

Actors Madhuri Dixit and Aishwarya Rai in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas (2002).

Actors Madhuri Dixit and Aishwarya Rai in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas (2002).

What do we lose when we lose song and dance from our culture?

What do things like poetry and song and dance allow for? They allow for multiple perspectives and open-ended meanings to coexist — something we struggle with currently.

Their loss means the removal of this additional layer of understanding from the cultural sphere, which privileges so-called value neutral (regional, religious, emotion-mukt) languages like law, rights, ‘proof’ as valid currencies. So, emotional experiences have to be expressed only in those terms, else they are not valid. Domination instead of heterogeneity becomes the goal of culture.

None of this is to say the opposite does not happen through Hindi song and dance too – stereotyping, rape-culture etc — but there are many counters within it as well. The template is open-source and all are adding to it, and so it produces a bouquet of films, aesthetics and experience.

If you look at the whole of Hindi film songs, you will be compelled to deal with heterogeneity, which is not conducive to large numbers preferred by nationalist or global corporate trends. So woke critiques can sometimes unknowingly become a part of the conformity machine, an immense homogenising process. Hindi films were conformity machines, too, but the song was the hatke thing inside the film. It was always subverting the film.

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05