MECCA, Saudi Arabia (RNS) — Saeed Khan is a 58-year-old Pakistani business owner living and working in Mecca, and this is the first time in 30 years that he is not performing hajj.

In the past, as many as 2 million Muslims have made the annual pilgrimage to Mecca.

This year, in efforts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus, Mecca has opened its door to only a fraction of that number.

“Health determinants are the basis for selecting pilgrims residing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and there will be no exceptions to anyone during this year’s hajj season,” the minister of hajj and umrah, Mohammed Salih Bentin, announced in early July.

According to the Saudi Ministry of Hajj and Umrah, those already residing in the country who have not previously performed hajj, are not government officials and are between 20 and 65 years old could apply for a hajj permit, which usually costs between $1,000 and $1,200.

Initially, about 10,000 people were expected to perform hajj this year. Most (70%) would be non-Saudis residing in the country, while Saudi citizens would make up the rest.

However, the number of people approved for hajj has been significantly lower.

Before being allowed entry into the holy city, pilgrims have had to also adhere to a “house confinement,” within their own homes, for a few days and then also be tested to ensure they do not have COVID-19 before being allowed to enter the holy city.

On arrival, all pilgrims performing hajj this year have stayed in a select number of four- and five-star hotels in Mecca, including Four Points by Sheraton, where social distancing and other protocols had already been implemented with consultancy from health officials.

Other health-related plans for hajj include, not unlike previous years, a number of field hospitals, clinics and ambulances.

Hundreds of Muslim pilgrims circle the Kaaba, the cubic building at the Grand Mosque, as they observe social distancing to protect against the coronavirus, in the Muslim holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, on July 29, 2020. During the first rites of hajj, Muslims circle the Kaaba counter-clockwise seven times while reciting supplications to God, then walk between two hills where Ibrahim’s wife, Hagar, is believed to have run as she searched for water for her dying son before God brought forth a well that runs to this day. (AP Photo)

However, due to the significantly fewer pilgrims this year, only a limited number of local doctors and other medical staff have been relocated to ritual sites.

“Our work hours are usually extended to 12 hours instead of eight during two weeks around hajj, and every second or third year, I have had to cover a three- to five-day shift at a hospital at Arafat or Mina,” said Dr. Shabeeh Haider, an ear, nose and throat specialist working for a public hospital. “But nobody from the hospital I work for has longer than normal duty hours this year, nor has anyone been asked to work from the hajj sites.”

Strict measures are in place to ensure only those with a permit enter Mecca.

Every year, just days before hajj, entry into Mecca gets restricted to just those with a hajj permit or those who are residents of the city. However, within the city, security is traditionally more relaxed, allowing residents to slip in and out of areas where the rituals are performed fairly easily.

“But they can’t really keep people from Mecca from performing; it is easy to slip through if you live here, so somehow I have managed to perform (the rituals) every year since I first moved here,” said Khan. “But this year is different.”

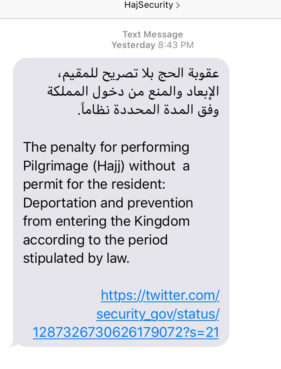

A text message about the penalties of performing hajj rituals without a permit. Screengrab

This year all roads directly leading to an area of hajj ritual have been shut off a week in advance to prevent Mecca residents without permits from taking part in the rituals.

At least 200 people have also been caught and fined or arrested for entering the holy city without permits in the week leading up to hajj, and Mecca residents have all been receiving text messages informing them of the fines for breaking the ban.

“We haven’t visited the Grand Mosque since March when, before COVID-19, I would go at least once a week. Even Ramadan, which is more of a lively and busy time here than anywhere else in the world, was spent under lockdown, and now the time of hajj is also feeling so barren,” Khan said. “Of course, this is the responsible thing to do and I respect the difficult decision the government made to value health over profits, but it is also emotionally a little difficult.”

For many residents of the city, however, the economic challenges are becoming increasingly difficult.

According to the Mecca Chamber of Commerce and Industry, about a quarter of the private sector’s income in the region around Mecca and Medina depends on pilgrimage.

More than 19 million pilgrims visited Mecca in 2019 for umrah, a smaller pilgrimage that can be performed yearlong; a significant proportion of those pilgrims visited during the holy month of Ramadan.

Last year 2.5 million pilgrims performed hajj.

Tourism provides the source of income for many residents of Mecca, many of whom are migrants and undocumented workers.

Mecca maintained the longest round-the-clock lockdown in Saudi Arabia; it was first implemented on April 2 and wasn’t fully lifted until late June.

“I’d make more in Ramadan and hajj seasons than I would in four other months combined,” said Anwar Yaseen, a taxi driver from India who is living in Mecca. “This year’s Ramadan was the most difficult time I have had financially in my life. Things are returning to normalcy now but only a little.”

Ramadan took place between April and May this year and Mecca was in a consistent lockdown throughout.

“It is a really strange time,” said Abdullah Al Maghrabi, a 27-year-old native of the city. “Never in my life did I expect the city to be so eerily quiet during hajj. My friends and I would always spend our evenings of the days before and after hajj in neighborhoods where lots of pilgrims would stay, get to know people from all over the world, and tell them about our lives here. This year is sad.”

Al Maghrabi works for his family business, a three-star hotel that caters to pilgrims. He said the hotel has been in a financial crisis since April.

Muslim hajj pilgrims circle the Kaaba, the cubic building at the Grand Mosque, in the Muslim holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Photo by Saudi Press Agency