Does ‘Impact’ Lie in the Eyes of Investors in India?

A 2017 McKinsey report found that impact investments in India could grow to US $6-$8 billion in 2025. This, however, is insufficient to achieve the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – an ambitious call to action for showcasing positive change. A 2019 Brookings India report indicates that India faces an annual financing gap of US $565 billion in achieving its SDG targets. Of course, it would be very difficult for the government to bridge this gap – and this creates a huge opportunity for investors to deploy their capital.

The famous quote by Peter Drucker, “If it cannot be measured, it cannot be managed” seems quite relevant for impact investors in India. In recent years, they have moved beyond counting high-level numbers towards intentionally considering impact as a key non-financial criterion in their investment decisions. However, there is no specific, well-accepted definition of impact, and there exist various impact measurement metrics.

Through an independent research project at The Fletcher School, I delved deeper into the impact investing landscape in India. This article explores how the country’s impact investors understand and measure impact, and examines how impact measurement is evolving there. These insights are gleaned from interviews with 10 experienced impact investors and practitioners in India. These investors work with organizations managing multi-million dollar funds and focusing on a range of sectors within and outside the country. For this article, the term “impact investors” specifically refers to fund managers and not fund owners.

The subjective interpretation of impact among investors in India

Most Indian investors associate investments in certain sectors with impact investing. They consider sectors like financial inclusion, renewable energy, healthcare, food and agriculture, education, and water and sanitation to be more aligned with an impact focus. The interpretation of impact, however, is subjective and varies with the type of investors in India. Most investors define impact based on their values, preferences and goals. This results in differing interpretations of impact even within sectors. Moreover, international capital owners and domestic fund managers also have disparate understandings of impact. For instance, some investors consider investments made by an international development finance institution (DFI) in an Indian e-commerce platform as an example of impact investing. They note large-scale job creation as a key impact metric. However, most impact-first investors debate this claim and do not consider such investments in e-commerce businesses as “real” impact investing. Instead, they consider such ring-fencing of impact as an example of “impact washing.”

The Impact Investors Council – a leading body to strengthen impact investing in India – has a member base of 23 active impact investors. However, most investors believe that there are only 10-12 impact-first investors in India that have dedicated impact funds. Others self-identified investors just have impact portfolios: that is, they only have a few impactful investees (business entities in which investments are made) in their portfolios. There are compelling advantages that lead fund managers to brand themselves as impact investors. Such branding helps in differentiating themselves from others, raising funds, enhancing visibility and publishing impact reports. There are various impact-focused limited partners (LPs), sovereign wealth funds, DFIs and European capital owners that invest only with investors that have some impact portfolios.

What Makes an Impact-First Investor in India?

In contrast to traditional investors in India who have adopted the impact label, the country’s impact-first investors adopt screening criteria to evaluate investment opportunities through an impact lens. Some investors have created a litmus test to assess impact. If the answer to the question “Can the investment opportunity create any positive impact besides generating some financial return?’’ is no, impact-first investors do not pursue such opportunities. Others use a bar of additionality to assess whether the impact would have occurred regardless of the investment.

Impact-first investors in the Indian market engage with potential investees to assess their impact potential. They gauge the motivation of core team members, and understand their social mission, focus sectors, geographies, target segments and impact metrics, if any. At times, they conduct deeper due diligence to review the alignment of impact with the mandate and portfolio of the funds. A few investors go a step further and conduct environmental, social and governance screening to avoid any negative implications. For instance, if an investee is a microfinance institution lending to businesses employing child labor, there can be business, social and reputational risks for the investors. Further, these investors remain cautious of the mission drift which may arise when investees focus on high growth targets and valuation.

India’s impact-first investors use proprietary impact metrics, often linked to globally accepted SDGs and the GIIN’s IRIS+ indicators. Their in-house teams of professionals create such metrics. They receive autonomy from capital owners (LPs) to create investee-specific metrics, which are reviewed on a bi-annual or annual basis to ensure relevance with time, changes in business models and the growth of investees. These metrics are, at times, co-created with the investees while discussing term sheets. This buy-in process is also used to decide on reporting methods and frequency.

The country’s impact-first investors differentiate themselves by measuring both the breadth and depth of impact. High-level indicators like the number of customers served, the percentage of women customers, the number of jobs created, carbon and food wastage, etc. are straightforward ways to cover the breadth of impact. Most of these metrics are captured in the monthly management information system report shared by investees. But impact-first investors use their expertise and legacy learning to measure the depth of impact, as well. Some go the extra mile to estimate the social return on impact, link outputs to outcomes and establish their theory of change. Some investors even share their approach and calculation methods with their investees, to capture subjective impact metrics – for instance, marginal benefits to farmers.

At times, capital owners inform and guide investors to create customized impact metrics. They share broad guidelines and criteria with the investors to measure the breadth of impact. Such indicators are often vetted by the internal investment committee and capital owners.

Measuring and reporting impact in the Indian market

Presently in India, impact data is self-reported by investees to impact investors providing equity capital. The frequency of data-sharing varies with the size of investees and their geographies of operations. While big investees have the resources to report data monthly, smaller ones working in rural areas share data quarterly or bi-annually. In contrast, impact reporting varies for impact investors offering debt capital. Debt providers face pushback from investees while sourcing impact data. Some borrowers consider them as “lenders” and question the requirement of impact data. At times, these borrowers have limited intent and resources to share the required data.

Often, the country’s impact investors accept the self-reported data at face value. Most of them have continuous visibility into their investees due to frequent review meetings. Further, most equity investors have board membership in their portfolio companies. For them, board meetings are a good platform to validate any information, as investees disclose complete financial and impact data. Though this is uncommon, a few impact-first investors sometimes audit impact data. Some generic impact data is also collected from financial statements, which are already audited. In certain cases, international DFIs conduct surprise audits to verify the accuracy of impact data reported by investees and impact investors. Such audits, however, are rare and infrequent.

For India’s impact investors, one compelling use of such data is publishing impact reports. Impact reports help them to generate interest from capital owners, as most international capital owners, especially DFIs are quite focused on positive impact. As a result, they prefer detailed impact reports to assess the impact created through their capital. To some degree, this has started to influence impact investing in the country. Impact reports also help impact investors to target new capital owners globally. Some suggest that the chances to raise follow-on funding from capital owners are reduced in the absence of comprehensive impact reports. Such reports also help impact investors to highlight positive impact and sector readiness in addition to financial returns. This helps them to build a case to raise follow-on capital from institutional and mainstream investors.

To some extent, impact reports also help India’s impact investors with their deal flow, by getting inbound interest from impact-focused investees. Such investees see some rewards in affiliating with impact-first investors. First, it limits the chances of mission drift arising due to a change in the investors’ business priorities and exit expectations. Second, investees prefer to leverage impact-focused investors’ experience and guidance to create and measure comprehensive impact metrics.

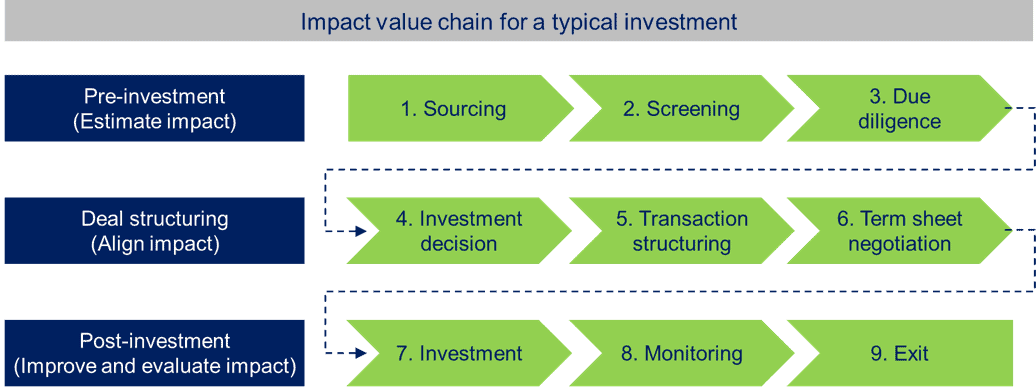

The graphic below indicates how impact can be linked to various stages of a typical investment.

An evolving impact investing landscape

Seeing the progress of impact investing in India, many believe that it will become an integral part of mainstream investing in a few years. But as of now, impact investors have only scratched the surface of the problems in the country. India also needs mainstream investors and innovative ideas to tackle complex social problems. However, with more impact investors continuing to provide proof of success, one can hope that some value-driven mainstream investors will shift their focus to impact investing. They can start by including non-financial criteria in investment decisions, and giving importance to the additionality, intentionality and measurability of impact.

As part of the process of mainstreaming impact investing in India, standardized, sector-specific metrics should become the common language for measuring impact. This will help investors to better understand each sector, evaluate portfolio companies more intelligently and compare sector trends. Most investors suggest that 8-10 standard metrics can cover the breadth of impact for each sector. Additional indicators, most of which are derivatives of standardized metrics, can be added to capture the depth of impact. Such a shared language will be useful in avoiding confusion and improving transparency over terminology in the industry. It will bring cohesion to efforts to define and report impact.

Of course, creating and implementing a standard measurement framework will be challenging. Even the now-ubiquitous internal rate of return took over three decades to be accepted as a concept. Standard metrics can be adopted from or aligned with the Impact Management Project, the SDGs or the GIIN’s IRIS+ metrics. The GIIN, along with impact investors themselves, has already started to create uniform metrics for different sectors. Such metrics can establish rigor in impact measurement and prevent “impact washing.” These metrics can be used to get accurate insights into direct and indirect impact at the customer, investee, portfolio and market levels in India. Such standardized metrics can challenge the sector to answer the question: Does impact lie in the eyes of investors?

This independent research project was made possible by Fletcher Educational Enrichment Fund (FEEF) and IBGC’s Experiential Learning Fund (ELF). Alnoor Ebrahim, Professor of Management at The Fletcher School, served as the faculty advisor for this research.

Mohit Saini is a Master of International Affairs candidate at the Fletcher School.

Photo courtesy of Carlos Muza.

- Categories

- Impact Assessment, Investing