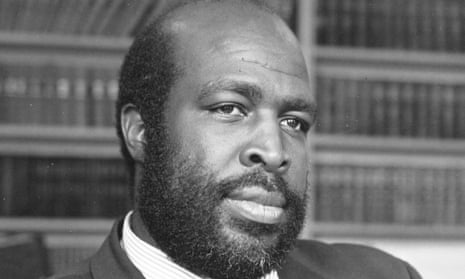

Lincoln Crawford, who has died aged 75, was a trailblazer for black barristers. He also contributed to an extraordinary range of public and voluntary bodies, in which his driving force was racial justice and the bringing of ethnic minorities into the mainstream of British life.

In 1981 he was instructed as the most junior member of the team of counsel to Lord Scarman’s inquiry into the Brixton riots of that year. The appointment displeased some members of the Afro-Caribbean community, who feared Lincoln’s involvement might serve to support a cover-up, but he rejected the criticism on the basis that participation was the route to progress.

He was on the Commission for Racial Equality for six years from 1984, acting as its chairman in 1985. That year too he was appointed to the Parole Board, and in 2001 he was made chairman of the Home Office slavery working party. He was also one of the earliest black recorders, and for 13 years was a part-time employment judge.

Lincoln received many appointments to conduct inquiries, often where racial disadvantage was an issue. His 1996 Crawford Report pinpointed racial discrimination in the London borough of Hackney’s employment practices, and in 1998-99 for the charity Mind he led an investigation into the impact of social exclusion on mental health.

Other inquiries he chaired included a 1996 review into the care and treatment of a mentally ill patient, Martin Mursell, who killed his parents after being discharged from psychiatric care, an investigation in 2000 into the employment policies and procedures of the British Council, and in 2001 an assessment of the fairness of schools admission policies in the London borough of Barnet.

Active in the Labour party, Lincoln served on the Inner London Education Authority for the constituency of Tooting (1986-90). He was also elected to the bar council, and became the first black chairman of its race relations committee.

Born in Moruga in Trinidad, Lincoln was raised largely in the countryside. His father, Norman, was a welder employed by a sugar company and his mother, Miriam (nee Lindor), was a seamstress. There being no books, newspapers or television, his knowledge of the outside world came from listening to the BBC World Service, from which the first thing he acquired was a devotion to Manchester United.

At the age of 18 he had a chance meeting with a Trinidadian, Johnny Ramoutar, who was living in London and had returned home for a visit, and who casually said: “Come and stay with me if you come to England one day.” Before long Lincoln had bought a one-way ticket on a cargo boat.

He arrived at Southampton in 1967 with just £3 in his pocket and moved on to London, where he knew nobody, save Ramoutar, and understood next to nothing of the country to which he had come.

Struggling for food and accommodation, on one occasion he walked five miles in response to a job advertisement, only to be told by a manager that the vacancy had already been filled. Then, looking down, his interviewer noticed that Lincoln’s boots were held together with glue and, taking pity, he not only offered him a different job, as a security guard, but also drove him home. Such acts of kindness made a profound impression on Lincoln, contributing to his wish to build bridges between races.

Eventually he passed some A-levels and secured a place to read law at Brunel University. Via a work placement while there, he saw the inside of Pentonville prison’s immigrant repatriation wing: he found this a harrowing experience, and years later became a trustee of the Prison Reform Trust. In his student days, too, he became aware of the large number of ethnic minority children in care, who seemed not to get adopted: that led later to research work for the MP David Owen on a private member’s bill, and eventually to his chairmanship of the Independent Adoption Society.

At Brunel he impressed a professor – John, later Lord, Vaizey – who recommended him for a barrister pupillage with Jonathan Sofer, a barrister in the chambers of Lord Rawlinson. In those chambers he again showed promise, and was offered a tenancy.

Despite growing success in his career at the bar and being appointed OBE in 1998, Lincoln never forgot what it had been like to be poor or isolated. He could talk comfortably to anybody, and, given a chance, invariably did. On one occasion in more recent years he was a guest at a lavish wedding party, where he appeared looking magnificent in white tie and tails. Later in the evening friends realised that he was nowhere to be seen, and so went looking for him. He was found behind a hedge, engrossed in conversation with some of the serving staff and members of a steelband that had been playing at the event.

The secret of his skill as a bridge-builder was, perhaps, the zest with which he lived life for each moment. He held on to his Trinidadian culture, and was a regular judge of bands at Notting Hill Carnival. But he became fond of British traditions, too, and felt perfectly at home conversing with members of the British legal or political establishments. He developed a considerable appreciation of classical music, with a particular interest in the 18th century mixed race composer Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

With his huge number of acquaintances, Lincoln straddled many worlds, and often did his best to link them. I recall a chambers Christmas party at which each member was encouraged to bring a guest: this normally meant a spouse, or else a partner. Halfway through the evening Lincoln arrived with his own invitee: the West Indies cricketer Clive Lloyd, whom he had once represented in a libel case.

In 1976 Lincoln married Janet Clegg, who was a student with him at Brunel. After their divorce, in 1999 he married Bronwen Jenkins, the daughter of the trade union leader Clive Jenkins, whom he met through the Labour party.

The later years of his life were blighted by the breakdown of his second marriage, which led to unhappy court appearances. He remained close to his five children – Douglas, Paul and Jack by Janet, and Ella and Mostyn by Bronwen, who survive him.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion