In her book, Family Papers: A Sephardic Journey Through the Twentieth Century, noted historian Prof. Sarah Abrevaya Stein follows the Sephardi Levy family of Salonica from the end of the 19th century, while it was under Ottoman rule, through the city’s transformation into present-day Greek Thessaloniki. Through her exacting investigation of a rich family archive—consisting of hundreds of newspaper articles and editorials, letters, medical certificates, passports, and photographs – she reconstructs the little-known story of Jewish Salonica, a once-thriving Sephardi community in the Balkans, and its immersion in the fate of European Jewry.

I was born in a place which, although at the other end of the Mediterranean, was very much like it: Tangier in Morocco. Both Salonica and Tangier were multi-ethnic and multi-religious cities whose societies were open, unprejudiced, and often economically prosperous. Together with several other port cities in that region, they embodied a distinct brand of Sephardi cosmopolitanism that has gone all but unnoticed in Jewish historiography.

Salonica has a rich and fascinating history. Situated on the northwest coast of the Aegean Sea, at the crossroads of Europe and the Middle East, it was well placed to thrive as a port city. Salonica’s prosperity was further spurred in the 15th century by the arrival of Jews expelled by the Inquisition from medieval Iberia (Sepharad) in 1492, who brought with them established trade networks. My own ancestor, an esteemed Iberian rabbi by the name of Daniel Toledano, traveled eastward to Salonica before turning west and settling in Fez, Morocco. These exiled Jews, often of a refined education and culture, spoke Ladino (or Judeo-Spanish). In the 19th century especially, Salonica was an important publishing and printing center for texts in Judeo-Spanish and Hebrew.

This work is an intriguing and necessary addition to the field of Sephardi studies, recently experiencing a substantial renaissance, with the insights of a new wave of historians like Stein herself, who teaches at the University of California in Los Angeles. Following in the wake of Mark Mazower’s pioneering work on the history of Salonica, Stein’s research on Jewish Salonica is part of a broader reframing of North African and Middle Eastern history. Mazower described Salonica’s transition from a multi-ethnic Ottoman society to a backwater renamed Thessaloniki after Greece captured it during the Balkan wars in 1912. Stein espouses this story from the Jewish perspective, but also seeks to cast a more intimate light at the city once dubbed “the Jerusalem of the Balkans.” Salonica had a considerable Jewish population of between 60,000 and 100,000, half the city’s residents in the 19th century. The city counted no fewer than 50 synagogues. Jews coexisted with Muslims, Greek Orthodox and other Christians as well as Dönme (the descendants of the self-proclaimed Jewish prophet Shabtai Zvi). These Jews were an integral part of the city’s labor force as stevedores and workers in the city’s tobacco factories. They also formed a middle-class of shop-owners, of teachers in the city’s schools, and finally of editors, printers and writers in the city’s most popular newspapers.

Sa’adi Levy, the patriarch of the family in Stein’s story, modernized a derelict printing press which his ancestor had brought in 1731 from Amsterdam, where the family had fled from the Iberian Peninsula, joining another important Sephardic center of Spanish exiles. He published Salonica’s most successful fin-de-siècle newspapers, the Ladino-language la Epoka and the French-language Le Journal de Salonique. The family also issued a dizzying array of other secular and religious writings and were soon established as part of the cultural elite of the city.

Levy’s newspapers covered the competing claims of Zionism, socialism, and the form of Ottoman nationalism known as Ottomanism. However Levy himself remained staunchly committed to the Sephardic legacy and language of his forebears (muestro Espanyol, as Ladino was also known). Sa’adi Lévy’s son Sam was also deeply immersed in the intellectual controversies of his time. In 1919 he even proposed a plan to the League of Nations in which he sought Jewish self-governance for his native city, whereby it would become a free and neutral city-state, neither Zionist nor Greek. In the momentous aftermath of World War I, Palestine was not readily embraced by Sephardi Jews in the Levant and North Africa as a viable destination.

The Levys counted journalists, teachers, and high-rank administrators among their family. Sa’adi’s son David, known honorifically as Daout Effendi, was a high-level official with tremendous power in the Ottoman hierarchy. Wishing to discuss the future of Ottoman Palestine, Theodor Herzl turned to him for an audience at the Sublime Porte. Daout was a patriot who bemoaned the end of Ottoman Salonica. Like a great many Salonican Jews, he feared Greek rule, and the nationalism that came with it. The Levys were also merchants, who built up a textile trade with Manchester in England that linked with other Sephardim around the Mediterranean in cities like Tangier. Sa’adi’s daughter Fortunée and her husband Ascher Salem established themselves as the Manchester branch of the Levy family.

Stein paints a skillful, if sometimes fragmented, picture of Sa’adi Levi, and his numerous offspring from the late 19th century to the present. She is a relentless researcher and follows their fates in eight different languages across three different continents – an astonishing feat. Their lives, like myriad others from that part of the world, have usually remained voiceless and undocumented.

As though to settle a point in the Ashkenazi-Sephardi cultural wars, Stein claims that Sephardi history is not fundamentally different from Ashkenazi history, though its encounter with modernity surely came in a different guise. While Central and Eastern European Jewry experienced a profound transformation under the impulse of the Jewish Enlightenment as Haskala, emancipation, secularization, and an enormous out-migration to Western Europe and the Americas, the Sephardic world underwent its own, different mutation when the Alliance Israelite Universelle made its appearance in North Africa and the Levant.

This bourgeois, reform-oriented Franco-Jewish philanthropic organization educated thousands of children from Morocco to Iran and provided them with a secular French education with a smattering of Jewish learning. Loyalty to French culture became the cornerstone of Jewish education from Tetouan to Teheran. Other common characteristics, observes Stein, were: “an embrace of innovative politics, emigration, measured assimilation.” Stein similarly challenges traditional perceptions of Sephardi societies as predominantly patriarchal. She observes shrewdly that progressive Sephardi families (much like Ashkenazi ones) oftentimes were more open-minded with their daughters than with their sons and did not hesitate to expose them to novel ideas. They believed that women would lack the will to stray, unlike the men. Some of the wives and daughters are strangely absent, but other women are richly visible. One example is Saa’di’s daughter Rachel Carmona. An excellent student at the Alliance school, she continued her training at the Alliance’s Ecole Normale Israelite in Paris. As an Alliance teacher, she traveled with her husband, a fellow teacher, to the organization’s schools in its vast network across the Balkans, the Levant, and North Africa. She taught in Ruschuk, Bulgaria – home to an important Sephardic community and the birthplace of the writer and Nobel laureate Elias Canetti – and in Tetouan, Morocco.

Stein describes a society which was both mercantile and intellectual, equally engaged in commerce of commodities and ideas. The two strands were often enmeshed in Mediterranean Sephardi societies, particularly those of several coastal cities which served as its cultural and commercial outposts, including Livorno, Alexandria, and Tangier.

The congruities between Salonica and Tangier indeed struck me, despite different timelines. Tangier Jewry only began its growth in the early 20thcentury, and its population never exceeded 15,000, about one third of the overall population.

Jews, however, were highly visible. Up until the 1950s, there were 22 synagogues in the city. I was born well after the pinnacle of Jewish Tangier, when it had lost its past luster and become a seedy backwater (today it is experiencing a renaissance, though nearly all its Jews have left), but my childhood in the 1970s was punctuated by nostalgic calls from older relatives lamenting the days when, on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, the city came to a complete halt.

As in Salonica, too, Tangerian Jews played a significant part in initiating a Jewish and non-Jewish press in Morocco. Figures such as Pinhas Assayag and Abraham Pimienta from Tangier played a major role, as did Levi Cohen, owner and publisher of the French-language weekly Le Réveil du Maroc, founded in Tangier in 1883. In the years following the start of the French protectorate in 1912, the Jewish press grew even more vibrant.

Likewise, Jews were facilitators, intermediaries, dragomans, skilled artisans, traders and moneychangers: commerce was central to the city’s life. My own family counts rabbinical and legal scholars, merchants, high-level administrators (one of them, Yahya Zagury, rather like Daout Effendi, organized the legal status of the Jewish community within the French protectorate in Morocco).

This role intensified with European penetration in the latter part of the 19th century. Many acted as trade representatives well into the last century in exchange for foreign protection. My maternal grandfather obtained a Dutch passport, though he never set foot in the Netherlands, just as some of the Levys in Salonica had earned Portuguese citizenship (this would later prove crucial in saving several of the latter from the Nazis).

What was the secret of this success?

In the early years of the 20th century, a long tradition of commingling in the confines of Tangier’s medina or old city laid the foundation for a close-knit economy among the three communities. A few wealthy bank-owning Jewish families such as the Abensurs, Benchimols, Hassans, Nahons or Parientes enjoyed personal and business connections with the local Muslim administration and the European diplomats living in Tangier.

Bolstered by free trade, commerce flourished further as Tangier gained in 1925 its much-vaunted International Zone status. Merchants who traded in commodities of all kind prospered. My grandfather, Aaron Cohen, and his brother Jacob were engaged in the wholesale import/export business. But they also made their money in a bustling real estate market as Tangier’s population grew rapidly in the 1930s and expanded beyond the walls of the old city. They bought land to develop new residential areas and built lodgings and cinemas to satisfy the tastes of a Westernizing elite. My mother recalls long afternoons watching the latest American features at the family-owned movie theaters, the Lux, the Goya and the Alcazar.

Tangier’s prosperity continued after the World War II, as Europe lacked basic products of all sorts, and the international city was able to provide plenty. The city’s free-wheeling ways are recounted endlessly in tales of espionage, and accounts of its cosmopolitan, if old-fangled elegance abound. As in Salonica, cosmopolitanism bred a specific religious mindset. It was orthodox but never rigid. One of the Levy descendants euphemistically termed it in French “pas fanatique” (not fanatical). My Tangerian relatives could have said the same. This period lasted until Morocco regained its independence in 1956, well before I was born.

The fate of each city’s Jews diverged, however. 98% of Salonica’s Jewish population was eradicated in the Holocaust, a calamitous distinction in Sephardic history. Nonetheless, Tangier had a narrow escape. In breach of the city’s international status, General Francisco Franco’s Spanish troops captured it in June 1940, the same day the German army marched into Paris. Had Franco entered the war on the side of his Fascist allies, I shudder at what could have happened.

Stein’s book paves the way for future studies on such cosmopolitan cities as Salonica or Tangier. Both epitomized what should aptly be viewed as “the Sephardi model,” one that’s not easily replicated anywhere else.

Confined in an academic framework, the book has the weaknesses of its virtues. Although it is to be praised for its faithful historical rendering, I wish Stein had kindled more of the Levys’ human warmth. A richer portrait of Rachel Carmona, for instance, would have been welcome. There are still human gaps in the story begging to be filled. But Stein is a historian, after all, not a novelist.

This shortcoming fades in the last part of the book: the chapter on Vital Hasson, a monstrous character who helped the Nazis in the extermination of Salonican Jewry and was tried after the war for his crimes, is the most affecting. Stein recounts the devastation he wrought in his wake. But perhaps this is both a strength and a flaw, as though Jewish history only becomes more richly inhabited when linked to the Holocaust. Equal narrative potency is needed elsewhere in the book when confronting the quandaries of Sephardi history.

What Sephardi story is told in Stein’s book?

Is this a tale of the greatness and decline of one Sephardi family? Or the unfortunate story of the demise of the entire Sephardi legacy? Where is that Sephardi heritage to be found today? And how did that heritage take root in its new homes: did it adapt, mutate, or stay the same?

One of the photographs in the book portrays the Salem family at the grave of Fortunée Salem in Manchester in the 1930s. Stein notes a meaningful and poignant detail: a bouquet of flowers – a practice from their new British world – rests on the grave, instead of the traditional stones. Something was lost in that passage, but what is it? The answer, not a simple one assuredly, is missing from the book and I regretted Stein’s reluctance to engage with the question.

I don’t presume to have the answer either, but I think it is a question worth exploring. When I visit my father’s grave amidst the tall cypresses and the colorful bougainvillea in Tangier’s Jewish cemetery, I still notice the discreet little rocks scattered here and there. Tangier’s Jewish history is now finished. The stones are hence double symbols of absence – of the deceased and of a defunct community. But I refuse to view them as fossils. Perhaps those pebbles, real and metaphoric, still exist elsewhere, vestiges of these vanished worlds. Perhaps they have even become flowers in their new settings today. ■ The writer writes about Sephardi culture and is currently working on a book about Sephardi women writers

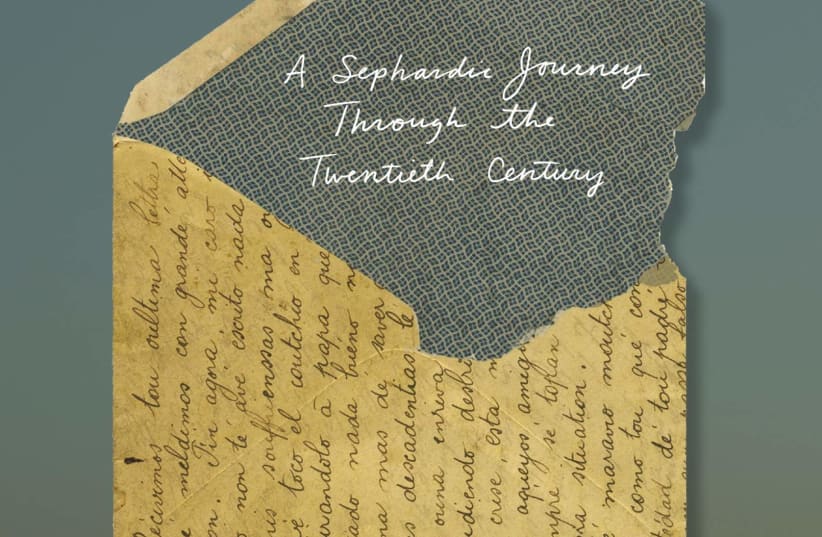

Family Papers: A Sephardic Journey Through the Twentieth Century

Sarah Abrevaya Stein

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

337 pages; $18.69

Yaëlle Azagury