Science news in brief: From dolphin fingers to quartz parasols

And other stories from around the world

Dolphins have hidden fingers

Put a dolphin’s front flipper in an X-ray machine, and you will see a surprise: an arc of humanlike finger bones. The same goes for a sea turtle, a seal, a manatee and a whale. All of these animals had four-legged ancestors that lived on land. As their various lineages adapted to life in the water, what had been multi-digit limbs slowly transformed into flippers.

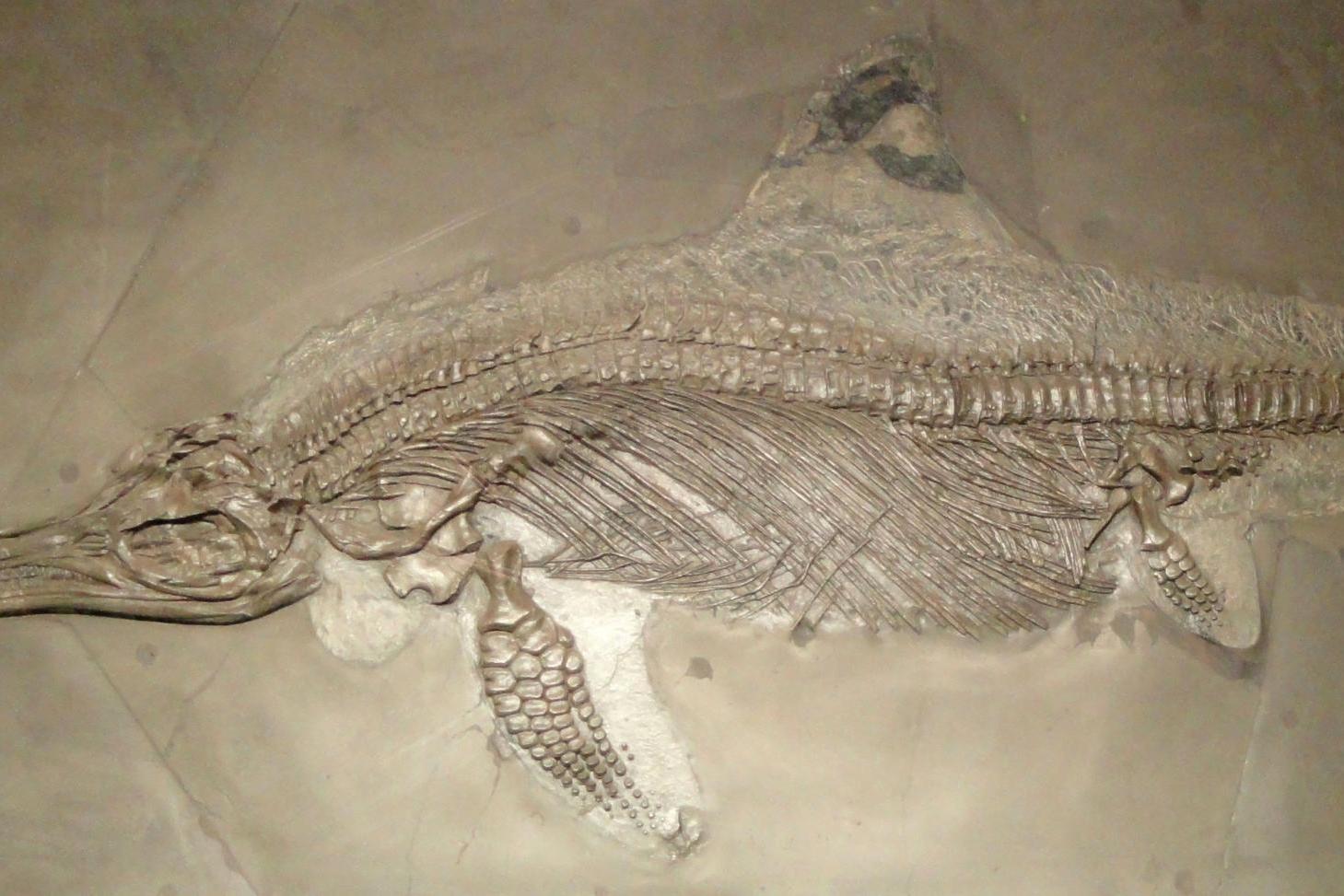

For a paper published in Biology Letters, researchers compared the flipper bone structures of 19 marine species with terrestrial ancestors, from species around today, like dolphins and sea turtles, to now-extinct creatures, like mosasaurs and ichthyosaurs that swam the oceans in the dinosaur era.

A majority, including most of the still-living animals, stuck close to the original blueprint, the researchers found. But some now-extinct creatures tried more creative strategies to adapt to aquatic life that have since been lost to time.

For this study, the researchers wanted to know how one function – swimming – had inspired the development of a number of unique limb structures. To do this, they needed “to compare things that are not directly comparable”, like a sea turtle flipper and the five-fingered limb it came from, said Evangelos Vlachos, a researcher at the Museum of Paleontology Egidio Feruglio in Chubut, Argentina, and one of the paper’s authors.

Network analysis allowed the researchers to convert each animal’s skeletal fin structure into an abstract web of nodes and connections. By comparing this network with the similarly broken-down limb structure of a landlubbing ancestor, they could see which of the creature’s bones had been gained, lost, fused, connected or otherwise re-jiggered since its terrestrial days.

Almost all of the animals kept their fingers, the researchers saw. The digits are connected to one another by surrounding skin and tissue, and can’t move independently. It is as though they are inside “a baby mitten”, Vlachos said.

Other than penguins (whose ancestors evolved wings before they returned to the water), all of the living aquatic animals in the study pursued this strategy, Vlachos said. Some now-extinct creatures, such as plesiosaurs and ancient crocodiles, had fingers in their flippers as well.

The exception was ichthyosaurs – thick-bodied reptiles that ruled the seas through the early Jurassic period. Their ancestors also had fingers. But over time, they connected to each other until they were less like a multi-branched tree and more like a dense bush. “They ‘lost’ their digits by reintegrating them,” Vlachos said.

Cara Giaimo

Why chimp mums flock to caves on the savanna

Everyone needs to cool off on a scorching summer day, even chimpanzees. Where do the primates go on sizzling days when woodlands and forests don’t provide respite from the heat? Caves.

But not just any chimps. New research shows that on Senegal’s savannas, home to a population of chimpanzees that has long fascinated scientists for their distinct behaviours, you are more likely to find mama chimps than adult males or non-lactating females hiding out in cool caves. Their visits coincided with the hottest times of day and became more frequent during the hottest months of the year, according to the study published in the International Journal of Primatology.

They also made these visits despite the risks of encounters with predators, showing how important the locations are for helping them survive and bring up babies in a challenging landscape that is threatened by human activities.

In southeastern Senegal, temperatures spike to 43C and fires burn large parts of the landscape over a seven-month dry season. Several natural cave formations pock the terrain, and they can be up to 12C cooler than the surrounding grasslands. The region is also home to the northernmost population of western chimpanzees, a critically endangered subspecies that mostly lives in large swathes of open grasslands and woodlands in this area.

Kelly Boyer Ontl, a primatologist at Ball State University, Indiana, and lead author of the new study, said: “I was really interested in finding out what chimpanzees are doing in caves, when are they using it and who’s going in there.”

In 2010, a local hunter introduced Boyer Ontl to Drambos Cave. He had observed small parties of resident chimpanzees go in and out. So, Boyer Ontl set up a camera facing the entrance of this “living room-sized” cave for 325 days between 2011 and 2013. The camera captured nearly 14,000 images of 45 total chimpanzee cave visits, involving 35 individuals – 17 adult females (10 of which were nursing mothers), three adult males, five juveniles and 10 infants.

Of those 45 visits, 42 were by the lactating females. The mothers arrived in parties of four, on average, along with their infants. They spent most of the time resting, socialising and grooming, while the infants played with one another. Sometimes, the mama chimps brought along snacks: fruits of the African baobab and camel’s foot tree.

“The cave isn’t a lactation room for nursing chimps,” Boyer Ontl said. She had noticed that the visits peaked in April and May – the hottest months of the year – and around noon, when temperatures reached their maximum. “It’s a cooling centre to rehydrate.”

Priyanka Runwal

When bugs crawl up the food chain

Epomis beetle larvae look delicious to frogs. They are snack-size, like little protein packs. If a frog is nearby, a larva will even wiggle its antennae and mandibles alluringly.

But when the frog makes its move, the beetle turns the tables. It jumps onto the amphibian’s head and bites down. Then it drinks its would-be predator’s fluids out like a froggy Capri Sun.

We tend to think of food chains moving in one direction: bigger eats smaller. But nature is often not so neat. All around the world, and maybe even in your backyard, arthropods are bodying vertebrates and gobbling them up.

Jose Valdez, soon to be a postdoctoral researcher at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research, identified hundreds of examples of this phenomenon in the scientific literature, which he detailed in a review published in July in Global Ecology and Biogeography. He and others who study the topic think that once the initial gasp of shock is past, it is important to understand what eats what.

Valdez became interested in these role reversals during his doctoral research, after watching a gang of water beetles devour a rare tadpole. The larvae were known predators, whereas the adults were widely considered to be scavengers. But Valdez developed a hunch, borne out by further research, that they were actively hunting vertebrates, too.

He got a similar feeling when, while reading the news or surfing YouTube, he saw other bugs punching above their weight: a huntsman spider savouring a pygmy possum, a praying mantis chewing off a gecko’s face.

“Maybe this is not so rare,” Valdez remembered thinking.

Valdez found 1,300 similar examples, which he gathered into a searchable database. The entries cover 89 countries and involve many types of arthropod predator: storied vertebrate-hunters like scorpions and spiders, along with less well-documented cases such as dragonflies and centipedes.

It is a formidable catalogue of invertebrate vengeance: a spider snares a songbird in its web, giant water bugs wrestle snakes into submission, fire ants team up to overrun a baby alligator. “Every time I would read a new one I was like, ‘Oh my goodness’,” Valdez said.

Cara Giaimo

There are two ways out of a frog

It is a familiar story: predator hunts prey. Predator catches prey. Predator gulps down prey.

Usually, that is it. But the water scavenger beetle Regimbartia attenuata says: “Not today.” After getting swallowed by a frog, this plucky little insect can scuttle down the amphibian’s gut and force it to poo – emerging slightly soiled, but very much alive.

The bug’s transit through the digestive tract can last as briefly as six minutes, a measly fraction of the two or more days it typically takes for a frog to fully digest and defecate its dinner, according to a study published in Current Biology.

“This is a weirdly wonderful behaviour that I hadn’t heard about before,” said Carla Bardua, an evolutionary biologist at London’s Natural History Museum who wasn’t involved in the study. “That a little beetle can actively swim through a digestive system is peculiar and amazing.”

Shinji Sugiura, a biologist at Kobe University in Japan, has been cataloguing the strange shenanigans of insects and their predators for years. Some bugs, for instance, goad toads into puking them back up after they have been gobbled.

“Insect morphologies and behaviours always inspire me,” Sugiura said in an email, adding that he is particularly keen on defences against predators that seem “unimaginable”.

After noticing that Regimbartia beetles and frogs frequent the same paddy fields in Japan, Sugiura brought together one specimen of each in the lab, expecting the insect would be spit out. Instead, it rocketed out the other end of the digestive tract – a faecal feat that Sugiura managed to capture on film.

Eager to test the behaviour's limits, Sugiura repeated his experiments with five species of insect-munching frogs in the lab. A whopping 90 per cent of the beetles they swallowed made it out the other end alive, all within six hours of being gulped down.

Katherine J Wu

This moss uses quartz as a parasol

To humans, a desert oasis may conjure an image of a blue pool encircled by a coronet of palm trees. But to certain mosses, an oasis takes the form of a pebble of milky quartz. The cloudy crystal dilutes the sun’s piercing ultraviolet rays and, in the dry desert heat, traps moisture beneath it, creating a microclimate perfect for a moss.

Kirsten Fisher, a biologist at California State University, Los Angeles, first spotted these miniature oases in 2014, somewhere off a highway in the western Mojave Desert in Wrightwood, California. She was studying the sex life of the moss Syntrichia caninervis, and progress was slow.

“They’re never having sex,” she said. “For a moss, it’s maybe once every 30 years.”

The site was studded with crystals eroded from a nearby mountain striped with pearlescent quartz. While waiting for Jenna Ekwealor, now a doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, to finish up a transect of S caninervis growing in the dirt nearby, Fisher picked up one of the many glittering rocks scattered nearby and, she recalled, saw a brilliant green carpet of the moss underneath: “And I said, ‘Holy moly, there’s moss under this rock’.”

Ekwealor was sure the green moss was a fluke. It had not rained in Wrightwood for at least two weeks. But as she and Fisher flipped over more rocks, they found several patches of strangely moist moss. Fisher and Ekwealor published documentation of this relationship in the journal PLoS One.

“I never thought to look under the rocks,” said Brent Mishler, a biologist at Berkeley who studies Syntrichia but was not involved with the research, with an exaggerated face-palm over Zoom. (Mishler has mentored Fisher and Ekwealor.)

Sabrina Imbler

© The New York Times

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies