In a banking year already characterized by widespread deferrals, heavy reserving and

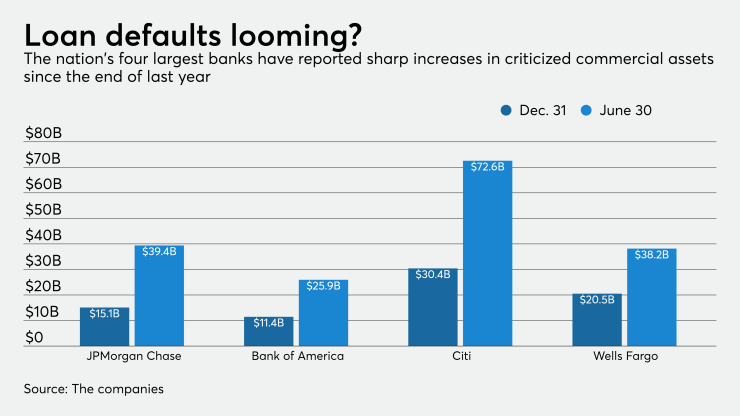

Criticized assets — loans classified as special mention, substandard or doubtful — soared at many banks between Dec. 31 and June 30, according to the latest quarterly filings. In particular, criticized commercial loans more than doubled at three of the four largest U.S. banks during that period.

Not every one of these loans will default, but several industry observers say the category bears watching this year and into 2021 — especially if the number of COVID-19 cases continues to surge nationwide and uncertainty lingers about the depth of the pandemic recession.

Corey Goldblum, a principal with the risk and financial advisory group at Deloitte, said loan deferrals, mortgage forbearances and the temporary increase in unemployment insurance payments — which expired July 31 — have held down the levels of nonperforming assets and net charge-offs. As a result, the actual credit picture is murky at best.

“Even the criticized assets that you see in the second quarter don’t really tell the full story yet,” said Goldblum, who advises banks on credit risk. “The government support has sort of masked what the true credit risk is because we’re ultimately not … seeing deterioration yet. But it’s coming.”

The coronavirus pandemic upended any sense of normalcy for banks this year. In the early days, the industry

During the second-quarter earnings season, some banks began to report a

In mid-July, Jamie Dimon, chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, told investors and analysts that he anticipated a “much murkier economic environment going forward than [we] had in May or June.”

There isn’t much more clarity a month later, said Peter Winter, an analyst at Wedbush Securities. A second round of government support has not been approved and the health crisis isn’t improving. On Wednesday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cited 55,540 new COVID-19 cases since the prior day, pushing total U.S. infections to 5.1 million. Total deaths are nearing 164,000 across the country.

“If we can get these COVID cases under control and get people back to work and the unemployment level goes back down and businesses reopen, then the criticized loans should start to recede,” Winter said. “What makes it difficult is that every day we’re seeing huge increases in cases … and if they don’t start to stabilize or a vaccine takes longer, at some point these criticized loans are going to turn into nonperforming assets and the banks will start charging them off.”

Analysts have offered mixed forecasts on the severity of loan losses. During a bank investor conference this week, Janney Montgomery Scott analyst Christopher Marinac said two banking companies, Hancock Whitney in Gulfport, Miss., and Cadence Bancorp. in Birmingham, Ala., reported a decrease in deferrals.

In a filing, Hancock Whitney, which has $33.2 billion of assets, said deferrals peaked at $3.6 billion on May 14 then began to decline, totaling $622 million on Aug. 2. In a separate filing, the $18.9 billion-asset Cadence said loans with active payment deferrals decreased from $1.4 billion on June 30 to $671 million on July 31.

“It kind of gives you a little bit of confidence that the economy isn’t that bad,” Marinac said. “Sure, we have our challenges, COVID is still with us and the pandemic isn’t over, but I think the ability for businesses to handle it is pretty good. That’s not meant to diminish the experience of hotels or restaurants or others where definitely business is struggling. But not every business is struggling.”

Yet problem credits rose in the first half, especially in business lending, and will be scrutinized the rest of the year.

At JPMorgan, criticized commercial assets more than doubled to $39.4 billion in the first six months of the year. Meanwhile, Bank of America said criticized commercial assets went from $11.5 billion as of Dec. 31 to $26 billion as of June 30. In its quarterly filing, BofA said:

“While we experienced increases in commercial nonperforming loans and reservable criticized exposures as a result of weaker economic conditions arising from COVID-19, we did not see meaningful impacts to consumer portfolio delinquencies, nonperforming loans or charge-offs during the six months ended June 30 due to payment deferrals and government stimulus benefits.”

Citigroup, Wells Fargo and U.S. Bancorp also reported higher levels of criticized assets. In Citi’s corporate credit portfolio, criticized assets rose by 139% to $72.6 billion.

Citi said it “expects a higher level of net credit losses during the remainder of 2020, partially offset by the release of existing reserves.”

According to

Marinac and other industry observers say they expect banks to keep building reserves and criticized loans to increase. A recent report from Accenture predicts that banks will set aside up to $320 billion this year to cover potential credit losses. That’s assuming an L-shaped recovery, the company said.

Alan McIntyre, head of Accenture’s global banking practice, said U.S. banks are being cautious as they “plan for the worst and hope for the best.”

“What we’re seeing here is the calm before the storm where there’s a real disconnect between the levels of provisions versus the actual losses,” he said. “The government help is masking the stress. … But there’s a recognition that at some point the government programs are going to run out and banks’ balance sheets will take more of the strain.”

It’s unclear if in fact a second round of government support will happen. Earlier this month, lawmakers took recess without reaching a deal.