- India

- International

Mohammad Nissar, India’s first and furious pacer that it lost to Partition

Mohammad Nissar bowled India's first ball in Test cricket, took its first wicket, and its first 5-wicket haul. However, a chain of events started by World War II and Partition resulted in his remarkable achievements being forgotten.

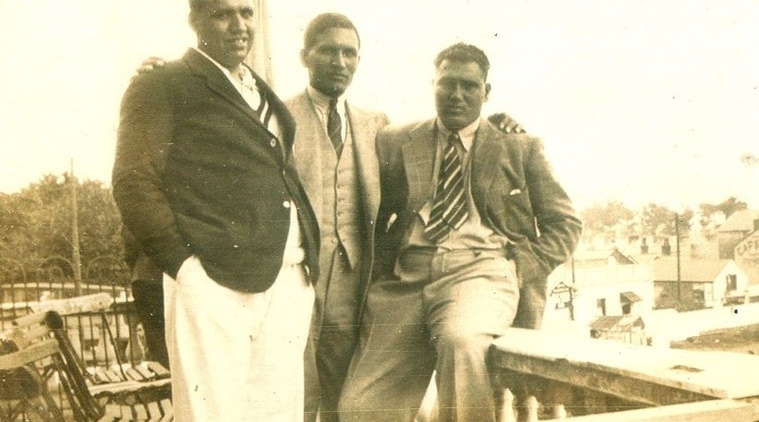

Mohammad Nissar (middle) cuts a colossal figure (Special Arrangement/Waqar Nissar)

Mohammad Nissar (middle) cuts a colossal figure (Special Arrangement/Waqar Nissar)When a stocky Mohammad Nissar ran in to bowl India’s first ball in Test cricket in front of 25,000 people at Lord’s in 1932, the visitors weren’t expected to give England much of a contest. Before the Test began, no non-white team had even played Tests.

The English opening pair of Percy Holmes and Herbert Sutcliffe had put on a world-record 555 runs for the first wicket just nine days earlier. On that day, both were bowled by Nissar.

Sutcliffe was dismissed by an inswinging yorker, and Holmes with a delivery that caused the off-stump to perform a spectacular cartwheel. When Frank Woolley was run out soon after, the mighty Empire was tottering at 19/3.

Grainy video of a stump flying off the screen as Mohammad Nissar bowls Percy Holmes on this day in 1932 in India’s first Test match. pic.twitter.com/S9lj829RhF

— Rameses (@tintin1107) June 25, 2021

Within the first 20 minutes of the match, Nissar, and his new ball partner Amar Singh, had got the ball to rise from the pitch “like the crack of doom” and had made the cricketing world sit up.

England did recover from the shock of losing their top order in Nissar’s opening spell to post 259 on India’s first day in international cricket. At the end of Day 1, India were 30/0, with Nissar’s 5/93 the best performance of the day.

For two whole days – the next day was a rest day – Indian cricket dared to dream. Outside Lord’s, children were imitating Nissar’s run-up and action, said historian Ramachandra Guha.

Percy Holmes is bowled by Mohammad Nissar (Special Arrangement/Waqar Nissar)

Percy Holmes is bowled by Mohammad Nissar (Special Arrangement/Waqar Nissar)

‘Can lay claim to be part of an all-time India team’

“It is ironical that India – a land known for great spin pairs and batting pairs like Bedi-Prasanna and Sachin-Dravid – had a pace duo as its first world-conquering partnership,” Guha told The Indian Express.

“Vijay Merchant and Nissar would be the only two players from the pre-War years who can lay claim to be part of an all-time India team,” he said.

However, a chain of events started by World War II and Partition resulted in India’s first pace bowler fading from memory. This, in spite of Nissar taking the country’s first Test wicket, and its first 5-wicket haul.

“It is unfortunate that there are no stadiums or pavilions named after Mohammad Nissar. The Indian side thinks they will not honour him because he is a Pakistani. The Pakistani side thinks that he played for India and so they do not need to honour him,” said his son Waqar Nissar from Lahore.

READ | ‘Now I’ll show you’: Balwinder Sandhu on how a bouncer to the head in the ’83 final fired him up

In that first Test, India’s dream stayed alive till the afternoon of the third day. CK Nayudu and Wazir Ali were batting at one stage with the score 110/2, but England pulled things back to bowl India out for 189. They won the Test the next day by 158 runs.

“It was my father and the 1932 team that took subcontinental cricket to the world. Within two years of that match, England were in India to play three Tests. This was unusual. They would have seen that the Indian team was special, that they could give competition,” Waqar said.

An unsuitable ending

When India got their second chance to play a Test, this time at home against England in 1933-34, Nissar opened the bowling and took another 5 wickets in an innings.

England almost went undefeated on that tour, with one blemish: a 14-run defeat to the Maharaja of Vizianagram’s XI in Benaras. Nissar was the star of that match as well with figures of 9 for 117.

In 1936, India toured England for the last time before the Second World War stopped Test cricket for 10 years. Nissar took a 5-wicket haul in the third Test of the series, but was called back to the country before the end of the tour by his employers, Indian Railways.

Mohammad Nissar, from a @BritishPathe video of the 1936 Oval Test (cc : @congusmaximus ) pic.twitter.com/3Wt33A641o

— Rameses (@tintin1107) December 3, 2018

“He was under tremendous pressure to return during the Test. They had told him if he did not return, the job would go to someone else,” said Waqar.

“Since that ’36 tour, he played cricket only at the convenience of his job,” he said.

Suvam Pal, a Beijing-based journalist who is working on Nissar’s biography, said the bowler’s job with the Indian Railways would have been very important to him given cricket wasn’t a profession yet.

“He would also often drop out of Ranji matches and Pentangular matches after this because of office commitments,” said Pal.

At 26, that was Nissar’s last match in international cricket. He finished with the unique distinction of having picked up a five-wicket haul in both his first and last Test.

An All-Indian bowler

Representing India in the 1930s was complicated business. Newspaper reports of the time referred to the side that travelled to England in 1932 as The All-Indian side. The Civil Disobedience movement was at its peak, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru were behind bars, and cricketers like Vijay Merchant had boycotted the tour.

“Merchant came from a nationalist family. They supported the Freedom Movement. Cricketers from princely states, like CK Nayudu, were not part of that boycott,” said Guha.

“For Mohammad Nissar, the fact that he was a Muslim would have caused certain complications. It would have caused problems in going to England, for instance. After the 1934 Eden Test, a newspaper report said that Nissar had not been able to perform because he was on his roza,” he said.

Waqar tried to explain his father’s political stance.

“He knew that the Partition was going to happen. Many of the Nawabs wrote him letters pleading with him to stay on the Indian side. But his heart was in Lahore. Whichever side of the border Lahore would be on, he would belong there,” he said.

Dilawar Hussain, Jahangir Khan and Mohammad Nissar, Indian cricketers from Lahore (Special Arrangement/Waqar Nissar)

Dilawar Hussain, Jahangir Khan and Mohammad Nissar, Indian cricketers from Lahore (Special Arrangement/Waqar Nissar)

“He just wanted to play cricket, he was not a political person at all. Even after the Partition, he selected the first Pakistan team, but left cricket administration after that because of politics. He was invited to all the matches, he used to go because he wanted to remain close to the game,” Waqar said.

Pal said Nissar was a “gentleman cricketer who believed in the spirit of the game”.

“During a Pentangular match between the Hindus and Muslims, captain Wazir Ali instructed Nissar to bowl bouncers at Vinoo Mankad’s head. Nissar refused,” said Pal.

This gentlemanly nature might have played a role in his selection to the first Indian side.

“During the trials, Amar Singh’s brother Ladha Ramji, another genuinely quick bowler, peppered the Maharaja of Vizianagram with bouncers to the body. He was not selected,” said Pal.

The last pacer

Many of Nissar’s contemporaries, like Merchant, said he was the fastest bowler in the subcontinent.

CK Nayudu said that early in his spell, Nissar was faster than even Harold Larwood, considered to be the fastest bowler in the world at the time.

Waqar recalls Dilawar Hussain, the India wicketkeeper from Lahore in the pre-Partition side, telling him that he used to keep meat in his gloves when keeping to Nissar.

“One of his jokes was that he could hear batsmen farting whenever Nissar started his run-up,” he said with a laugh.

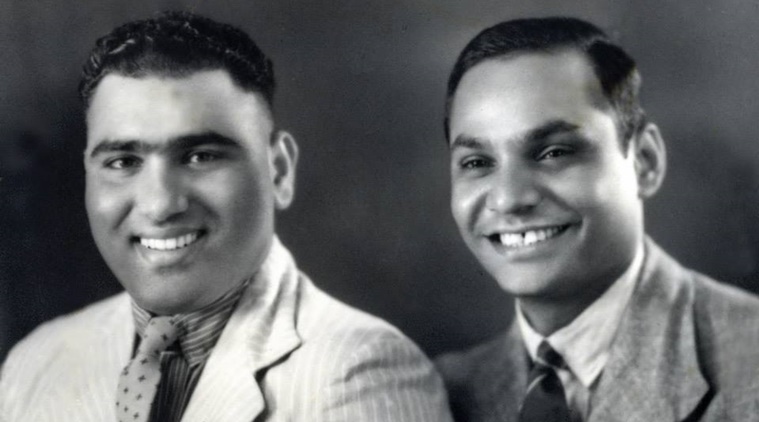

Mohammad Nissar and Amar Singh – the opening bowlers for the first Indian Test team (Special Arrangement/Waqar Nissar)

Mohammad Nissar and Amar Singh – the opening bowlers for the first Indian Test team (Special Arrangement/Waqar Nissar)

But then came Independence and Partition. In 1952, Vijay Merchant wrote, “Above all, the Partition has deprived India of future fast bowlers.”

Guha said Merchant’s prediction of how India’s pace resources would be affected after Partition would have been drawing on stereotypes of the time, but it did turn out to be true for half a century.

“Our pacers in recent times have proved this to be wrong, but it was true for many years. India did not produce fast bowlers,” he said.

“There are two big reasons why we did not have world-class fast bowlers from the 1930s up to Kapil Dev’s time. We always produced slow turning pitches in domestic matches, and there were no role models for fast bowlers,” Guha said.

Pakistan-based historian Tariq Saeed said Nissar is considered the first in a long line of fast bowlers for the team across the border.

“Nissar holds the distinction of being claimed by both Islamia College and Government College in Lahore, the two biggest teams in the country then. Munawwar Ali Khan, the fastest bowler in the first Pakistan team, considered Nissar his idol. Mahmood Hussain, the fastest bowler in the next decade, was Munawwar’s protégé,” he said.

Lost legacy

Nissar remained in touch with his Indian teammates with letters from Lahore, but was never able to visit his birthplace Hoshiarpur in Punjab. He continued working as a travelling officer in Pakistan Railways. He carried his kit bag around with him and played cricket matches with local teams everywhere the train would halt for the night.

“He would not bowl with the 22-yard run-up he had been famous for, he used to run in from 4-5 yards. But people would come to watch him from all around,” said Waqar.

Waqar still remembers his first brush with playing cricket was in one such match in a remote hilly area of Balochistan, then called Hindu Bagh, later renamed Muslim Bagh.

In 1963, Nissar died of heart failure in a train compartment on one such journey, his cricket kit close by.

READ | When India defied history but inspired a Caribbean tactical revolution

In 2006, the Indian and Pakistan cricket boards came together to institute the Mohammad Nissar Trophy, a match to be played between the domestic champions of India and Pakistan. Uttar Pradesh and Mumbai won the first two years. Sialkot won the third and last match in 2008, even though a Delhi youngster, Virat Kohli, was named as the Man of the Match. As political ties worsened, the tournament was stopped.

However, one of Nissar’s artefacts is still in India: the match wicket from that first Test in 1932. It bears the signatures of all the Indian and English players. But Waqar doesn’t know where it is, having handed it over to the Indian cricket board when it had said it would set up a museum.

“What saddens me is that I could have gotten them restored myself. I could have given them to Pakistan’s board, England’s board or even ICC, but I gave it to India because I thought it was a part of Indian cricket history,” he said.

Get latest updates on IPL 2024 from IPL Points Table to Teams, Schedule, Most Runs and Most Wickets along with live score updates for all matches. Also get Sports news and more cricket updates.