Fraud charges, lost patents: How an L.A. auto legend’s China venture crashed

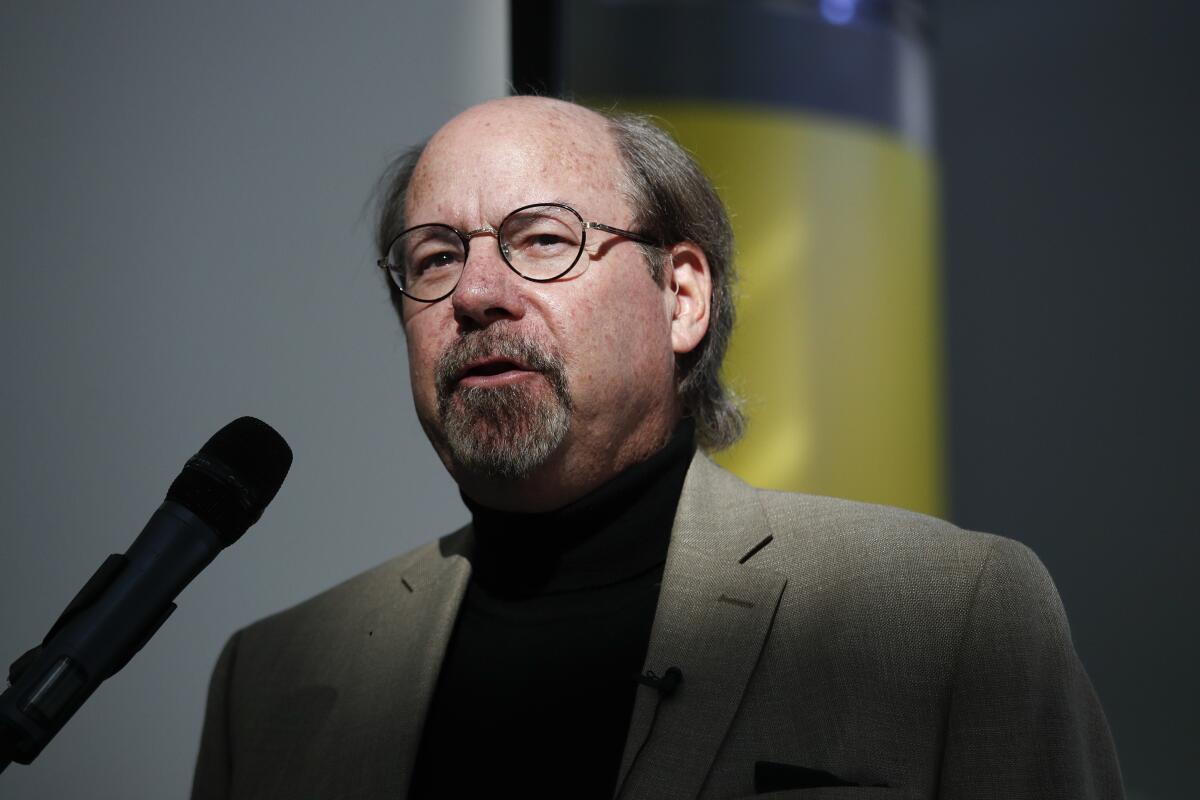

In July 2019, Steve Saleen, the Southern California designer of souped-up Ford Mustangs and eponymous supercars, walked onto a strobe-lighted stage at Beijing National Stadium to launch a new line of vehicles for the Chinese market.

During a 90-minute spectacle featuring techno beats, mesh-clad dancers and an appearance by the British action star Jason Statham, Saleen introduced himself as an automotive legend whose partnership with Chinese state investors would inject “supercar DNA” into high-end sedans, coupes and an SUV aimed at younger drivers.

A year later, that flashy vision has veered disastrously off track.

Saleen’s Chinese backers have accused his business partner of fraud and embezzlement and taken over the company, freezing its accounts and forcing hundreds of employees out of work. Police raided the sprawling new factory emblazoned with Saleen’s name. Two senior executives were detained, and a court order sealed its Shanghai showroom.

Saleen alleges the Chinese shareholders planned to steal his intellectual property and have filed for more than 500 Chinese patents for his designs and technology. Stories in China’s government-owned media offer a different account — one of a flailing startup that squandered public funds on the launch while its first vehicle flopped, and whose technology was worth far less than the state shareholders had been led to believe.

The story of Saleen’s joint venture with the government of the eastern city of Rugao began with yet another American entrepreneur wading into China with dreams of building a lucrative global business.

That promise foundered on miscalculations, suspicions and the inexperience of a sports car guru who knew more about engine tuning than financial maneuverings. Saleen says he’s become a cautionary tale about dealing with China, where the alleged theft of foreign companies’ trade secrets — and an opaque legal system that favors China’s state-backed companies — has offered grist for the Trump administration’s deepening cold war with Beijing.

It was the great microchip heist — a stunning Chinese-backed effort that pilfered as much as $8.75 billion in patented American technology.

“What I’m trying to do is to bring to light how American companies will contribute IP, brands and knowhow to the China market — and overnight they will change direction, kick you out and keep the IP,” Saleen said.

The dispute could go to arbitration in Hong Kong, where Saleen’s business partner — Chinese-born U.S. resident Charles Xiaolin Wang, who was investigated years earlier by U.S. authorities — has sued the Rugao government for breach of the joint venture agreement. In an interview, Wang denied the fraud allegations.

Whatever the outcome, Saleen’s bid to bring his high-powered cars to China has crashed, leaving the 71-year-old filled with regret.

“When it came to taking my brand on a global basis, it really seemed to offer me an opportunity that I could not refuse,” Saleen said. “In hindsight I realize the deal was too good to be true.”

The Inglewood-born Saleen, who raced Ford Mustangs competitively in the 1970s and 1980s, made his name as a master modifier of the iconic American muscle car. Fitted with superior engines, suspensions and transmissions at his plant in Irvine, Saleen’s customized Mustangs frequently bested Porsche and Ferrari on the track and cost far less, putting high-performance race cars within reach of American enthusiasts.

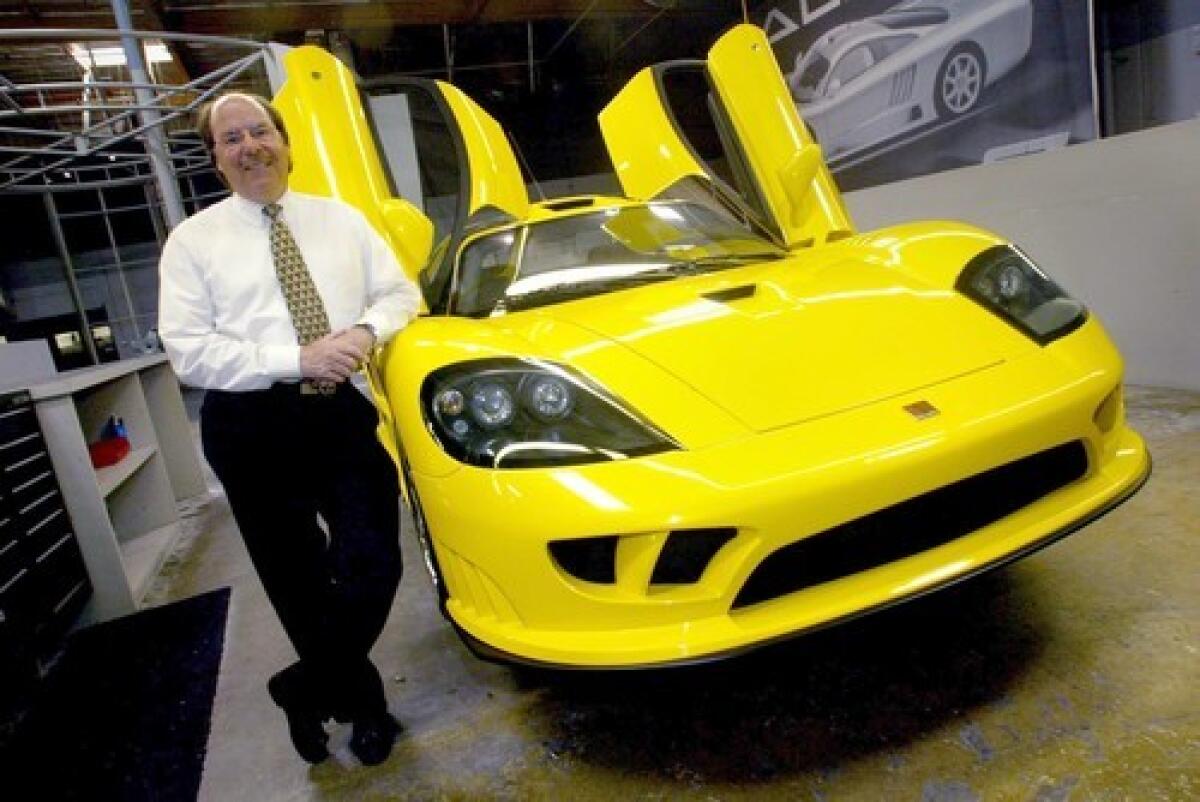

In 2000 he debuted the S7 — a low, sinuous two-seater with wing-like doors, designed and built from the ground up — which went from 0 to 60 in 2.8 seconds and soon became one of the world’s premier supercars.

His roster of celebrity clients grew to include Tom Cruise and Derek Jeter, but some dealers and contractors began to complain about missed deliveries and bounced checks. In September 2014, Saleen Automotive reported to the SEC that it had just $7,261 cash on hand and owed more than $5.6 million to suppliers, banks and the IRS, raising “substantial doubt” that it could stay afloat.

A potential lifeline emerged in 2015 with a visit to Saleen’s factory in Corona by a delegation from Rugao, a city of 1.4 million built on farmland in the Yangtze River delta, two hours north of Shanghai. Officials told Saleen they dreamed of building “a mini-Detroit” and were looking for a big-name auto company to come in and create jobs.

The dealmaker was Wang, a Duke-educated lawyer and businessman with connections in China but a checkered history.

Federal regulators had investigated Wang’s earlier auto venture — an electric car company called GreenTech that was also backed by former Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe — for alleged abuse of a program that solicited foreign investment in exchange for green cards. Although no charges were brought, GreenTech’s plans to build battery-powered vehicles at a plant in rural Mississippi fizzled.

Lawsuits by the state and unhappy Chinese investors followed. The company filed for bankruptcy in 2018.

Saleen shrugged off the legal trouble, calling Wang, whom he’s known for a decade, “very honorable and straightforward.” The pair took a majority stake in the joint venture, dubbed Jiangsu Saleen Automotive Technology, with Wang as the chairman and Rugao pledging $1.1 billion in capital and loans. Saleen, the vice chairman, put up no cash, but the deal valued his expertise and technology at $800 million.

It was a staggering amount, especially given Saleen’s struggles in the U.S. Under the agreement, JSAT would pay his company tens of millions in fees to design and develop vehicles including the S1 — Saleen’s first all-new sports car in years — to be manufactured in Rugao for sale worldwide.

“Steve’s vehicle is different from all other mass-produced vehicles” in China, Wang said. “It’s high-performance and it requires a lot of technical specialty which, even today, nobody in China knows how to do.”

The deal helped Saleen’s U.S. company more than double its revenues, turning a $5.5-million loss in 2018 into a $2.5-million profit the following year, according to SEC filings. Saleen flew back and forth between the U.S. and China as JSAT opened a corporate office in Shanghai, built two production facilities in Rugao and hired about 1,000 employees.

Then came the July 2019 launch at the national stadium, the former Olympic venue dubbed the “Bird’s Nest,” on which Wang told Chinese media he spent more than $8 million. Besides the S1, Wang showed off three prototypes: a new S7, an SUV and a battery-powered two-seater called the Maimai, Saleen’s entry into an overcrowded Chinese electric vehicle market dominated by the deep-pocketed Tesla.

The first JSAT model to go on sale in China, the petite Maimai left commentators scratching their heads. Its 109-horsepower motor and toylike design — some prototypes featured happy-face emojis on the hood, others a cartoon child on a bike — hardly matched Saleen’s brawny brand.

In fact, the Maimai was an updated version of the MyCar, the low-speed vehicle that Wang had planned to build in Mississippi. Reaction to its shape, and hefty $22,000 price tag, was withering.

“There are numerous superior (in performance, range and practicality) options available in the Chinese market at comparable or lower price points,” concluded a moderator on the ChinaCarForums website.

The car was a failure. Six months after its release only 27 Maimais were registered in the entire country, according to one state media report.

The trouble at JSAT burst into public view in April, when a former legal officer, Qiao Yudong, posted a lengthy statement online alleging that Wang had sold the Rugao investors inferior technology backed by fraudulent valuations, and funneled cash to his wife and associates. Qiao claimed the Rugao government had spent close to $1 billion of public funds on a joint venture that had produced hardly any cars.

Wang rejected the allegations as the product of a disgruntled ex-employee, saying he had never controlled the company’s accounts.

After an audit by the government investor, Nantong Jiahe Technology Investment and Development, a district court in June ordered the closure of the factories and Shanghai office. Police raided the production plant, ordered workers to leave and detained the company’s German head of manufacturing, Frank Sterzer, for several hours until he was able to contact German diplomats to obtain his release. Sterzer, who remains in China, declined to comment.

The Chinese investors seized control of the board last week and have filed suit against Wang, who has been at home in the Washington area during the COVID-19 pandemic. He said he has no plans to return to China, believing he won’t get a fair trial.

As this was going on, Wang said he learned that the joint venture had quietly applied for auto design and technology patents related to Saleen’s work in China, many not listing Saleen as the inventor. Saleen alleged his Chinese partners were plotting to push him out from the start.

But according to their agreement, any intellectual property that springs from Saleen’s work in China belongs to the joint venture. That could complicate his efforts to contest the patent filings, experts said.

“In a normal joint venture there is always some tech transfer,” said Tycho de Feijter, an expert on the Chinese auto industry, who described the joint venture as a costly mismatch of expectations.

“Steve Saleen saw a lot of gold at the end of the Chinese rainbow, didn’t do proper research into his partners and had no idea what he was getting into,” De Feijter said. “Similar story for the Chinese side. They too saw gold where there wasn’t any, had no experience in carmaking and no idea about what or who Saleen really was.”

Wang, 54, took responsibility for the venture’s collapse.

“Steve is a genuine automotive guy; all he wants to do is make great cars,” Wang said. “He may not want to hear me say this — I don’t think he’s a very sophisticated, cunning sort of businessman. His whole world is simply making cars. And I got him into this mess. I feel sorry for that.”

Saleen said it was too soon to judge the impact on his storied brand. But Saleen Automotive’s most recent annual report to the SEC paints a dire picture, stating that the joint venture accounted for more than three-quarters of its income, and that “any reduction in business with JSAT would likely cause our revenues to materially decrease.”

With negotiations over a U.S.-China phase 2 trade agreement stalled, Saleen said his experience should convince Washington to enact tougher protections for U.S. investors, deny Chinese firms that steal trade secrets access to capital markets and prohibit the use of Chinese asset valuations that could be subject to manipulation.

“It’s too late for me,” he said. “What I do hope is that all American companies learn from my bad experience.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.