In the United States today, there are many voters who sympathize with Joe Biden’s positions on tax policy, Social Security, and reproductive choice — but just can’t abide the Democratic nominee’s plan to abduct small children, traffic them to Hollywood, and then let liberal pedophiles abuse and ritually murder the little ones before oxidizing their adrenaline into psychedelic drugs.

Of course, Biden has no such proposal (Uncle Joe won’t make peace with legal weed, let alone child-harvested “adrenochrome”). But in the world conjured by more than 1,000 Facebook groups that collectively claim millions of members, the Democratic nominee is staunchly pro-Satanism. The Americans who frequent these forums unironically are a deeply deluded sort. And yet their decision to embrace a hallucinatory worldview is, in many cases, a rational act (according to my own unorthodox theories, anyway).

Conceived in 2017, the QAnon conspiracy theory — which posits that Donald Trump is locked in a secret battle with a cabal of progressive pedophiles — has exploded in popularity amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Trapped at home as an invisible, inscrutable menace shuttered the world as they’d known it, denizens of various apolitical online communities became newly receptive to the gospel of “Q.” Others contracted Q-adjacent paranoias. Speaking with voters in Wisconsin this month, Time reporter Charlotte Alter heard conspiracy theories from about 20 percent of her interview subjects. Many of these Wisconsinites were not familiar with QAnon but subscribed to its basic tenets. Tina Arthur, a small-business owner, told Alter that she was not a follower of QAnon but did believe that the Democrats were in league with a cabal of blood-drinking child rapists and that “if Biden wins, the world is over, basically … I would probably take my children and sit in the garage and turn my car on, and it would be over.”

The worldview that gave rise to this contemplation of filicide has become alarmingly prevalent within the GOP. Next year, a QAnon proponent named Marjorie Taylor will almost certainly take a seat in Congress, after winning a Republican primary in a deep-red Georgia district last month. Trump has himself praised QAnon supporters, and one recent poll found a third of GOP voters saying the theory was “mostly true.”

The debate over how to combat this growing craze for tinfoil hats has been focused on the supply side of the problem. Which makes sense. Although the American people have always had an affinity for conspiracism, they did not always get their news from social-media platforms that outsource editorial judgement to algorithms, or a cable network that comports itself as an organ of state propaganda. But I think that the burgeoning demand for conspiracism also merits contemplation. It would be a failure of both empathy and analysis to attribute the far right’s psychedelic paranoia to sheer ignorance or madness. To the contrary, from the standpoint of an individual QAnon adherent or die-hard Trump supporter, the adoption of delusional political beliefs can be quite rational.

This may be easier to see in the latter case. The fact that ordinary conservatives have embraced conspiratorial ideas about the “Fake News Media” and “Deep State” — so as to protect their mythic vision of Trump from information that contradicts it — has had adverse consequences for many in their coalition. The president’s environmental deregulation has worsened air quality in many heavily Republican areas. His careless pandemic management has likely increased the number of Americans, conservative and otherwise, who’ve perished from COVID-19. But for most conservatives — as individuals — learning and accepting the truth about Trump would result in many social harms and no substantive benefit. The chance of any single voter’s ballot deciding an election is minuscule. Adopting a worldview antithetical to that of one’s family, church, and community, however, is bound to either produce profound loneliness and internal strife (if you keep your heresies to yourself) or social stigma and familial conflict (if you make your views known). Happily, evolution has equipped human beings with an array of cognitive biases that help us rationalize our in-group’s presumptions and look past information that contradicts those ideas. Relatively few conservatives will ever need to consciously decide to prioritize in-group harmony over critical thought. Were they faced with such a dilemma, however, there would be some rationality in choosing to believe in the irrational.

Belief in QAnon is less optimal as a means to the end of social conformity (talk of Satanic cabals is liable to raise a few eyebrows even in many conservative communities). But conspiracy theories serve other psychological needs.

The tendency toward conspiracism is deeply rooted in the human psyche. It manifests across time and geography and is likely a product of evolutionary pressures. On an emotional level, human beings tend to find the idea of being threatened by forces beyond their comprehension or control much more upsetting than being threatened by an intelligible enemy. Social psychologists have found that when fearful people contemplate potential misfortunes, they tend to feel helpless and pessimistic, but when angry people contemplate the same, they feel a sense of optimism and control. And one simple way to transmute fear into anger is to perceive an evil agent behind whatever development is causing you uncertainty and disquiet. (Confronted with apocalyptic wildfires of uncertain origin last week, many conservatives in the Pacific Northwest attributed the conflagration to “antifa” rather than to complex and amoral climactic forces.)

All human beings are subject to these impulses (at least if evolutionary psychologists’ theories can be believed). But some people have a stronger affinity for such modes of thinking than others. In a 2014 paper for the American Journal of Political Science, Eric J. Oliver and Thomas J. Wood sought to discern what, if anything, differentiated Americans who believed in conspiracy theories from their compatriots. Analyzing survey data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Studies, Oliver and Wood found that belief in various political conspiracies was most heavily associated with a broader disposition for believing that intentional forces exist behind visible reality and that history is driven by a Manichaean struggle between good and evil. Voters who harbor such tendencies exist on all sides of the political spectrum. But they are especially prevalent on the religious right, for intuitive reasons: Conspiracy theories, like fundamentalist theologies, posit that behind the maddening ambiguity and complexity of observed reality lies a straightforward conflict between the good and the wicked.

Oliver and Wood’s proposed link between belief in the supernatural and conspiracy theories finds anecdotal support in recent reporting on QAnon. During the pandemic, the far-right conspiracy theory found a receptive audience in online “wellness communities, religious groups and new-age groups” united by “shared beliefs about energy, healing or God,” according to NBC News. Despite QAnon’s pro-Trump political implications, many adherents of hippy-inflected, new-age spiritualities took to the narrative, a development that lends credence to the idea that ideology is less determinative of conspiracism than a psychological predisposition for believing an epic battle between intentional forces (whether they be God and the Devil or good and bad energy) shapes the world as we know it.

Critically, there is reason to think that the percentage of Americans inclined toward such modes of thought may be increasing. Anthropological research has found that in traditional societies, belief in “moralizing, personified gods increases when people are uncertain about the future.” At a time when much of the country is incapacitated by fire and infectious disease, it stands to reason that people might be feeling more uncertain about the future and, thus, more inclined to impose order on chaos by interpreting reality as a proxy war between good and evil agents.

Thus, the psychological benefit that QAnon provides its adherents seems clear: It transmutes feelings of anxious uncertainty and helplessness into moral clarity and purpose. The costs of believing in QAnon vary, depending on the strength of a believer’s fervor. Certainly, those who follow its logic into acts of violence will end up worse off for having encountered Q. But for more-passive conspiracists, the narrative may provide psychological comfort with little personal downside.

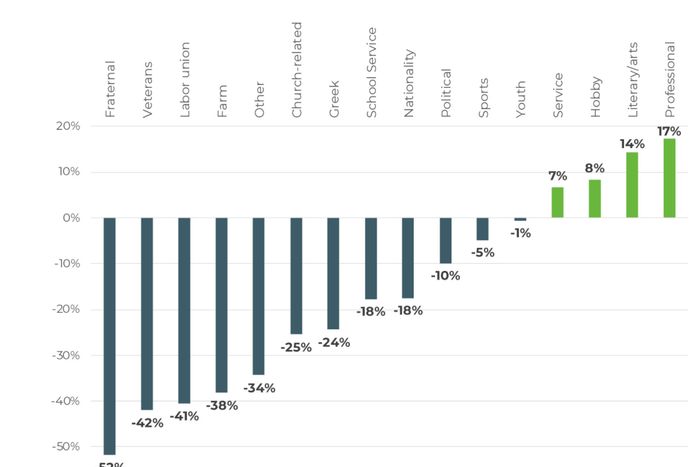

After all, for many Americans — perhaps for a majority — politics is not experienced as a venue for pursuing concrete social aims but rather as an unpleasant and anxiety-inducing genre of media. Over the past half-century, Americans’ participation in the institutions of civil society — from trade unions to churches to voluntary organizations — has plummeted. Even at the level of the neighborhood, communal bonds have withered as Americans report fewer interactions and mutually beneficial exchanges with those who live next door.

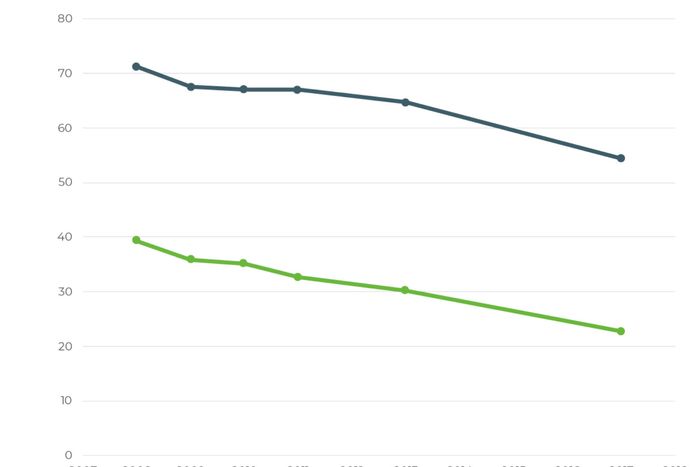

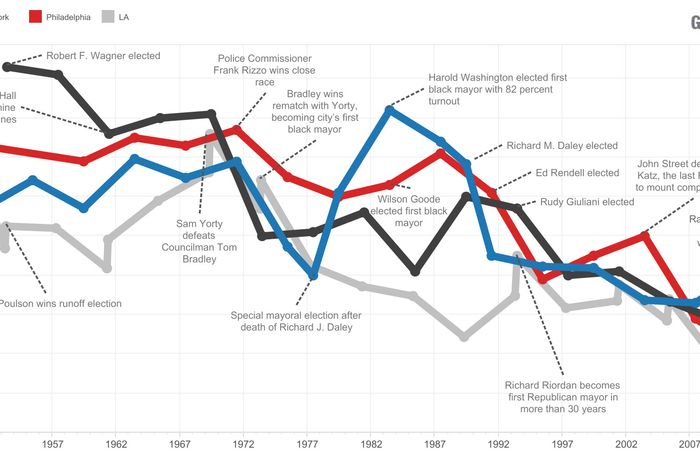

Voters’ knowledge of local politics, and participation in local elections — the level of government where they can exert the most direct influence and observe the consequences of policy with the least mediation by propaganda — has similarly eroded.

With the time freed up by abstention from civic and communal life, Americans gorge themselves on television: As of 2017, even as they increased their use of alternative forms of media, the average U.S. household still consumed seven hours and 50 minutes of TV a day.

As atomized spectators of national politics, ordinary voters have essentially no power to change political reality. So why would they bother to engage in the cognitively expensive work of attempting to discern it? Why, when merely understanding our nation’s problems can seem like a quixotic enterprise even for the civic-minded? America’s most prestigious economic thinkers spent much of the past decade preaching ideas about the relationship between inflation and unemployment that have proved utterly false. If macroeconomic reality — and, thus, the likely consequences of competing economic-policy proposals — remains opaque to such impeccably educated elites, what hope does the layperson have? And if ordinary voters cannot trust in the authority of established experts — who, let’s not forget, recently misled them into a ruinous war and financial crisis — what rational heuristic are they supposed to use?

Further, even if ordinary Americans had the time and resources to assemble a rigorous, evidence-based understanding of macroeconomics, climate, and geopolitics, what are they supposed to do with that knowledge? In the absence of strong civic institutions that can help them collectivize the costs of effective political engagement — and in the presence of giant constitutional and plutocratic barriers to major reform — might their education leave them with little more than an exquisitely precise understanding of why their nation’s politics are irrevocably broken? Conspiracy theories offer their adherents psychic protection against the onslaught of nerve-racking news. What does the truth have to offer them?

In playing anti–Satanist’s advocate here, I don’t mean to proselytize for nihilism. I think that it is still possible for ordinary people to make meaningful (if inadequate) change through existing political institutions. But appreciating the strength of the case for embracing far-right delusions may help to dispel a common center-left fantasy: that the rot in our democracy spreads from the minds of Trumpists out into civil society rather than back and forth between them.

Preventing demagogic conspiracists from further degrading U.S. politics will likely require finding effective yet non-repressive ways of regulating major tech platforms. But a comprehensive agenda for democratic renewal will need to find answers to the even more vexing question of how to revive civil society and participation in local politics. When voters are embedded in civic institutions and pursuing change in their immediate communities, they can engage politics as empowered, rational actors. When embedded in their living-room couches, watching nightly news reports about problems beyond their personal comprehension or control, voters will engage politics as spectators of an increasingly lurid reality show.