Juliette Gréco, who has died aged 93, was the most influential French popular singer to emerge immediately after the second world war. With her long dark hair, soulful eyes and deep voice, she became the musical embodiment of the existentialist movement. Although she seemed the most modern of performers, Gréco belonged to the grand tradition of Parisian chanteuses. Like her illustrious predecessors Damia, Yvonne George and Yvette Guilbert, she attracted poets and philosophers who found in her a modern femme fatale. Many of the songs she made famous were composed for her, but Gréco also sang some of the standard chanson repertory.

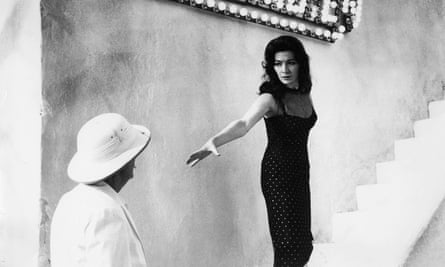

Her manner was simple: usually dressed in black, she would stand before the microphone and announce the name of the poet and composer. She deployed little of the showbiz formula: her stance was that of a priestess, someone with a deep and terrible knowledge of life and love, who was about to impart some of her secrets to the congregation.

“Gréco has a million poems in her voice,” wrote Jean-Paul Sartre, who composed lyrics for her. “It is like a warm light that revives the embers burning inside of us all. It is thanks to her, and for her, that I have written songs. In her mouth, my words become precious stones.”

Creators fell in love with her, men such as the jazz trumpeter Miles Davis, the film producer Darryl F Zanuck and the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, while her long hair, black clothes and disdainful expression attracted photographers including Roger Corbeau and Robert Doisneau. She met Davis when he was playing in Paris with Dizzy Gillespie. “Sartre asked Miles why we didn’t get married, but Miles loved me too much, he said, to marry me. ‘You’d be seen as a negro’s whore in the US,’ he told me, ‘and this would destroy your career.’”

Jacques Brel and Charles Aznavour wrote songs for her: in the late 1940s there was an explosion of cafe-theatres in Paris, among them Le Tabou, Les Assassins and La Rose Rouge, and it was at the last of these, one evening, that Gréco came off stage to find Jean Cocteau standing in the wings. “You sing for 200 people now, but it ought to be for millions,” he told her.

Juliette was born in Montpellier, in the south of France. Her father, Gérard Gréco, was Corsican, and worked for the local police force, but she and her elder sister, Charlotte, were brought up by their maternal grandparents in Bordeaux. When Juliette was seven, the girls’ mother, Juliette Lafeychine, reappeared to take them to live in Paris, in a small apartment in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the part of the city with which Gréco would always be associated.

After the fall of France in 1940, Juliette and her sister were sent to school in Bergerac. Their mother had joined the resistance, and one day, after the family had returned to Paris in 1943, when Juliette was going to meet her sister near La Madeleine church, they were arrested by the Gestapo.

She was made to sleep in a small cell, the light shining in her eyes. In her 1982 autobiography, Jujube, Gréco described the man who interrogated her and Charlotte. “I will never forgive him,” she wrote. “I know that I myself will fight until the last day of my life, against oppression, against intellectual terrorism, indifference and the denial of the only treasure that is worth preserving at all costs: the right to live as we choose, to think, to laugh, to give, to change, to love without fear whatever and whoever we love.”

Gréco was sent to the women’s jail at Fresnes, and was released after a few months, but not until after the war would she find that her mother and sister had survived. She returned alone to Saint-Germain-des-Prés where she was befriended by one of her former schoolteachers, Hélène Duc (who later became an actor). After the liberation of Paris in August 1944, she went every day to the Hotel Lutetia, where the survivors from the camps arrived in buses. One day she found her sister, who was so thin and wasted she could hardly walk.

Later the sisters took to frequenting a bar at the Hotel Pont Royal. Sartre, Albert Camus and Simone de Beauvoir met there, and through Merleau-Ponty, who had asked her to dinner – “he must have liked my face” – Gréco began to meet the young poets and dramatists who were talking about a new type of theatre.

She was engaged to read some of their poems for a series of experimental broadcasts. Only one of the group, Henri Michaux, objected to her style. “I’m only reading and saying what you’ve written,” she told him. “If you don’t like it, it’s hardly my fault.” Gréco had already acquired the cool manner that would make her famous.

During 1946 and 1947 she was frequently photographed as one of the “new young people” of Montparnasse. Then, one night at the cabaret Le Bal Nègre, at a table with Sartre and De Beauvoir was the writer Anne-Marie Cazalis, who, Gréco wrote, taught her “how to live and how to laugh again”.

Through Cazalis, she met writers including Boris Vian and Jacques Prévert. Cazalis encouraged Gréco to sing, but it was Sartre who took the decisive step. He gave her the words to a song he had written, but which had not been used, for his play Huis Clos.

This led to her first meeting with the composer Joseph Kosma. He had composed music for films by Jean Renoir and Marcel Carné, and gave Gréco a song he and Prévert had written for Carné’s 1945 film Les Enfants du Paradis, Je Suis Comme Je Suis, which set her on her singing career. Kosma also wrote the music for Sartre’s lyric, which became her first recording, La Rue des Blancs-Manteaux. Photographed on stage at La Rose Rouge, she became the image of Saint-Germain.

Davis came to Paris in 1949 – Gréco later described their relationship as “poetic and sensual” – but he did not want to live with her, knowing as he did about the pressures of racism. They remained friends for the rest of his life, and he visited her a few months before he died, in 1991. Gréco first got married in 1953, to the actor Philippe Lemaire; their daughter, Laurence-Marie, was born the following year, and they remained friends after their divorce in 1956.

During the mid-1950s Gréco made many film appearances in France, while in Hollywood she was in The Sun Also Rises (1957), The Naked Earth (1958), The Roots of Heaven (1958) and Crack in the Mirror (1960). She had a long relationship with Zanuck: the cigar-smoking mogul and the moody chanteuse made an odd couple, and their partnership did not outlast Gréco’s Hollywood career, but after Zanuck’s death in 1979 Gréco wrote that he had left a void in her life that was never to be filled.

Gréco had a hit with a 1965 television thriller series Belphégor, and in 1966, at a gala for the magazine Télé 7 Jours, celebrating all the stars who had been featured on its cover, she met the actor and director Michel Piccoli. A few months later they were married. After their divorce in 1977, her third and final marriage in 1988 was to the composer and pianist Gérard Jouannest, who often accompanied her later concerts. He died in 2018.

After 1970, Gréco became an emblem of what seemed a lost era. She was the last of the great chanteuses, and she toured the world with a constantly changing repertory of songs. They had usually been written for her, and when she sang them her control and concentration was that not only of a great singing actor, but of a survivor.

In the 90s she became president of the association to preserve Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the area which, she quipped, had “turned me into a marketable commodity”. After a pause of 20 years, she resumed releasing albums, which included Je Me Souviens de Tout (2009) and Gréco Chante Brel (2013), as well as another autobiography, Je Suis Faite Comme Ça (2012).

In 2016 she suffered a stroke, and the death of her daughter. Her final tour date was in May 2017, in Paris.

Juliette Gréco, singer and actor, born 7 February 1927; died 23 September 2020

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion