- India

- International

An IPL blockbuster starring: T Natarajan

A Tamil Nadu village fed on a diet of Rajni films has found a new hero in T Natarajan, the yorker king at this edition of the IPL who has reached dizzying heights.

T Natarajan has delivered 27 yorkers since the beginning of this IPL season. (Source: File)

T Natarajan has delivered 27 yorkers since the beginning of this IPL season. (Source: File)Just when the stifling April heat slows down life in Chinnappampatti, a village 36 km west of Salem in Tamil Nadu, the lives of two young fast bowlers would pick pace. It’s when Salem’s annual tennis-ball cricket tournament kicks off. From eight in the morning to eight at night, the two bowlers and their teammates would squeeze into share autos with their wooden stumps and bats, and hop from one village to the other. There was little to play for — no match fee, no transport allowance, cricket kits or shoes — except for the winner-takes-all prize money of Rs 25,000 (shared among two dozen teammates) and, if lucky, an imitation-gold trophy or a watch that the man of tournament took away.

But none of this mattered to them. Only yorkers did. That most physically demanding and difficult of all fast-bowling tools, where the margin of error is minimal, the energy expended enormous. For most tennis-ball bowlers, yorkers are a weapon of survival; for the two, it was also a weapon of emancipation — shaping for them a trajectory that would have been unimaginable less than a decade ago.

The older of the two bowlers, left-arm seamer T Natarajan, 29, has been the yorker king of this edition of the IPL. The Sunrisers Hyderabad bowler has already landed 27 in the block-hole in seven games; Jasprit Bumrah, the most vaunted yorker expert, has only been able to muster 17 this edition.

The younger one, G Periyaswamy, 26, known locally as the Salem Slinger for his Malinga-like bowling action, was the highest wicket-taker in the 2019 edition of the Tamil Nadu Premier League. He went unsold this IPL, though he has travelled to the Emirates as a net bowler for the Kolkata Knight Riders.

T Natarajan (left) and G Periyaswamy both hail from the same village in Tamil Nadu’s Salem district.

T Natarajan (left) and G Periyaswamy both hail from the same village in Tamil Nadu’s Salem district.

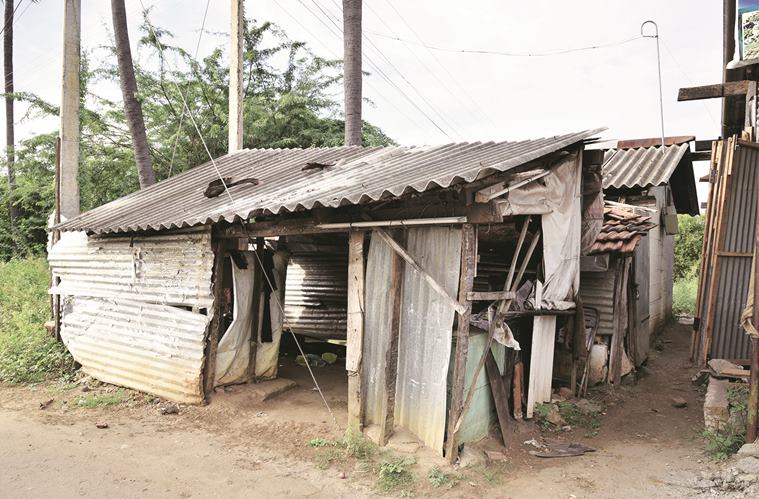

Nine years ago, Natarajan and Periyaswamy themselves would have shrugged off their storyline as pure fiction. Like most young men in the village, their dreams rarely strayed beyond its physical boundaries — Natarajan knew he would end up being a porter or a weaver like his father, and Periyaswamy would help his father in his tea shack. That’s when life took a rather sudden turn, much like in the Rajinikanth blockbusters that were once a big draw in the village’s two ramshackle cinema halls.

The storyline went thus: A failed district cricket player spots Natarajan, launches him in the Tamil Nadu Cricket Association (TNCA) league, from where he rises so dramatically that he’s picked in the state team, then the Tamil Nadu Premier League and finally the IPL, when Kings XI Punjab shelled out Rs 3 crore in 2017 to acquire him. He returns home a millionaire, turns his mud house into a bungalow and starts a cricket academy for the local children. All this in less than five years.

In 2018, Sunrisers Hyderabad bought him for Rs 40 lakh, and he has been with the team since then.

All along, he doesn’t forget his old friend, who is working as a weekly-wage labourer in a local kiln to pay off his father’s debts, takes him under his wings, develops him into a state cricketer. Together, they shared the new ball for Tamil Nadu in a Syed Mushtaq Ali tournament last year.

At times, even Periyaswamy wonders if it’s all real. So awestruck was he that he had an emotional breakdown during that Syed Mushtaq Ali Trophy match. “I was trembling, because I was bowling with my hero,” he says. A movie buff, he pauses and strikes a Rajinikanth parallel: “Namma ooru Rajini Nattu annan tha (The Rajinikanth of our village is Natarajan). I would say he is even bigger… a real-life hero.”

He recalls the conversation in 2017 with Natarajan that pulled him back into the game. “One evening, when I returned home from the kiln, he was waiting for me at my house and told me to quit the job. I explained my plight, about the debts my father incurred while paying for my medical bills (an illness early in life had led to loss of vision in his right eye) but he hugged me and said, ‘Don’t worry about anything. I will take care of your parents.’ That evening changed my life,” he says.

The Natarajan academy has two of the district’s six turf wickets.

The Natarajan academy has two of the district’s six turf wickets.

Periyaswamy spent the next six months at the Natarajan Academy, working on his bowling, and unlearning pessimism and learning to dream. At the end of the refresher course, Natarajan fetched him a contract with a TNCA fourth division club.

“I was afraid to dream when I was young, but anna (elder brother) told me that only dreams will take you places. Dreams and hard work. How could I disagree when the perfect example of that was right in front of me,” says Periyaswamy, talking from the UAE.

Like most IPL players, Natarajan’s ultimate goal is to play for his country, an achievable yet uncertain dream given how competitive the Playing 11 is. Even if he doesn’t earn the India colours, his rise has broader relevance. IPL has been familiar with rags-to-riches stories of small-town players but Natarajan’s goes deeper. It’s a heartening tale that points to Indian cricket’s ever-spreading geography and the ever-increasing reach of the T20 net. If the last decade was about the boys from Ranchi, Najafgarh, Jalandhar and Shrirampur giving competition to those from the big cities, Natarajan’s rise shows the cricket boom is reaching further down the kuchha road.

Natarajan’s story is unique also for how he is raising back the village that raised him, inspiring another generation of cricketers in this back-woodsy village. Chinnappampatti, undetectable in most maps, has, besides the two theatres, as many schools, five temples, two local restaurants and one bank. The Internet is wonky and electricity fickle, but the village has two turf wickets — both at Natarajan’s academy — while the whole of Salem district has just six. A few months after Natarajan’s first IPL stint in 2017, the academy came up in a half-acre land that belonged to his friend K Krishnakumar.

A cricket academy in Chinnappampatti would seem out of place. But it’s not, says A Jayaprakash, Natarajan’s mentor and the man who launched him into a cricketing career.

“The idea of the academy is not to make money; in fact it’s entirely free for the children who train here. Tell me, who will open an academy in such a remote place? And why? It’s because he doesn’t forget his roots,” he explains.

Natarajan realises he could easily have been the one to slip away unnoticed, if it wasn’t for Jayaprakash. So indebted is Natarajan to his mentor that on his SRH blazer is emblazoned ‘JP Nattu’ — JP for Jayaprakash and “Nattu” the name Natarajan goes by among family. Jayaprakash, who never progressed beyond district-level cricket, lives in the village and is four years older than Natarajan. In one of the club cricket games that they played in, Jayaprakash tossed a brand new leather ball in Natarajan’s direction and asked him to bowl. It was the first time Natarajan had ever held a cricket ball in his hands. And then came the yorker.

A week later, Jayaprakash gave him a pair of cricket shoes, a train ticket to Chennai and the contact number of a friend, who managed to secure him a contract with a fourth division cricket club in Thiruvallur, 40 km from Chennai. Within two years, Natarajan was bowling for one of the elite clubs of the Tamil Nadu Cricket Association league, Jolly Rovers, which had Murali Vijay, Ravichandran Ashwin and Jayant Yadav, among others.

The reason he started the academy, Natarajan recently said in a Sunrisers Hyderabad video, was to give the youngsters of the village the exposure he never had. “There was a time I used to bowl barefoot. Then I saved some money and borrowed some and bought a pair of shoes that I used for several years. I want the next generation to enhance their chances of making a career out of cricket,” he said.

N Prakash, the chief coach at the academy, says, “Whenever he comes here, he coaches the children, there are around 60-70 of them. He would be here by around 7 in the morning and stay till evening, talking, teaching. Sometimes, he invites state players to the academy.”

Three years into the academy, the efforts are already producing results. Besides Periyaswamy, two other youngsters have made it to the Salem district team — V Gowtham and Aravind.

Gowtham, academy coach N Prakash says, is their best-kept secret — “our next Natarajan… kandippa (certainly).” This is what Natarajan had envisaged when he set up the academy — to produce professional cricketers from his village. For Chinnappampatti to be the cricketing hub of Salem, which before Natarajan had produced just one first-class cricketer — left-arm orthodox spinner K R Sivaprakasham, who was dropped after one match in 1990.

To the children at the academy who tell Natarajan that their ambition is to become “like him”, he says, “Athukum mele (Even bigger).”

Natarajan’s first project from his IPL megabucks was to revamp his house. What was once a two-room structure with mud floors and a tiny verandah, is now the only two-storey house in the village. The floors are now a beautiful green ceramic and the walls, painted sunrise yellow, are covered with framed photographs of Natarajan with his parents, siblings and Jayaprakash. The gates to “namma veedu (our house)”, as the villagers call it, are always open.

In the Sunrisers Hyderabad video, Natarajan says his parents don’t understand cricket. It’s the same for most of the older generation in the village, who, like Natarajan’s father Thangarasu, used to work in the power looms that dot the outskirts of the village or in the cracker factories in neighbouring villages.

His mother Santha ran a food shack, with her nattu kozhi kulambu (country chicken curry) and beef fry the most popular dishes on the menu. From her meagre profit, she would set apart Rs 5 every day for her son.

“I knew it would not be enough for his bus ticket and food. But I would give him that during his college days. He might have had his needs, but he never asked for more than what I gave him,” she told Daily Thanthi TV after he got picked up by Kings XI Punjab. The village — whose entertainment once revolved around the Friday movie releases, the temple festivals during the month of Margazhi, jallikattu and the raunchy ‘record dance’ — now gets its kicks from cricket.

Though the villagers are still learning their cricket, they are an intense and involved audience. On the day of his matches, there are prayers at the local temples. And when he comes home, they burst crackers and distribute sweets, and take turns to invite him for lunch or dinner.

He brings them unalloyed joy. “It’s pure love… It’s like a festival here,” says Prakash, the coach at the academy.The love stems less from Natarajan’s fame, more because he has given the village an identity. “He is as grounded as he has always been, very loving and affectionate. He listens to the same old songs, walks barefoot in a lungi when he’s home,” says Periyaswamy.

The experience, Periyaswamy says, is akin to watching a Rajini movie. Or, as he adds, “more than a hero”. He is the superstar of Chinnappampatti. But Natarajan’s dream run stuttered early on. Soon after Natarajan’s first-class debut in 2015, he found his name in the list of bowlers called for suspect action.

“I was gutted, I saw my dreams crashing down,” he had told this paper in 2017, recalling the nightmare. He was sent for action correction to the Tamil Nadu Cricket Association Academy. Among the coaches and biomechanics experts there who worked on Natarajan’s action was former Tamil Nadu spinner Sunil Subramaniam.

“I could imagine what he was going through. His financial condition then was poor and his entire family depended on him,” recalls Subramaniam, who was influential in the growth of Ravichandran Ashwin too. But his background turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

“Unlike the city lads, he didn’t have any hang-ups. He was willing to listen, to change and practice. Natarajan was determined to bounce back,” says Subramaniam.

For Natarajan, the first six months at the academy were filled with self-doubt.Retooling an action is far from easy. The fundamental problem was his loading, recalls Subramaniam. His shoulders were falling away and hence, he was loading up too far away from the body. The change was a seemingly minor rectification, but one that called for immense practice and unlearning. So everything from the run-up, the gather, loading and release had to be realigned.

Here again, his past helped. “Thankfully, he hadn’t played much with the leather ball and not come through structured age-group programmes. So it was comparatively easier,” says Subramaniam.Thus began an intense regimen, wherein he would first shadow bowl with his new action, then bowl with the ball in hand but not hurl, then gradually start bowling without a run-up, then run-up with two strides, then at full pelt, first without a batsman at the other end, then with one playing defensive strokes and then finally a batsman playing attacking strokes.

“It’s when the batsman starts attacking a bowler that the old habits kick in. But Natarajan didn’t, which showed his adaptability and will power. It takes 13,000 balls for the new action to set in, and I think he might have even bowled more,” Subramaniam says. That’s when Subramaniam realised that he was watching a special player, one with exceptional grasping skills. “Most of the time, we just showed him visuals, and he would make the corrections himself. And remarkably, he didn’t lose much pace or sting, which happens to most bowlers after correction,” he says.

Far from it, he has only grown sharper and returned reenergised to win back his first-class stripes and clinch IPL fame.

This dream script, though, is still being written. As Natarajan tells Ashwin in the latter’s Hello Dubai ‘aa video blog episode: “I want to play for India.” Irrespective of how, and when, that happens, an entire village will be behind him, cheering for their superstar.