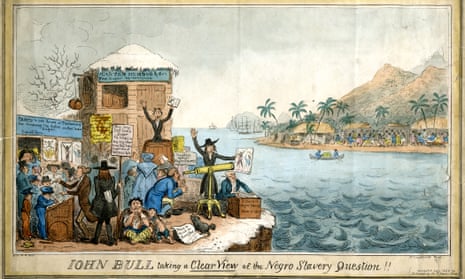

Britain’s national myth about slavery goes something like this: for most of history, slavery was a normal state of affairs; but in the later 18th century, enlightened Britons such as William Wilberforce led the way in fighting against it. Britain ended the slave trade in 1807, before any other nation, and thereafter campaigned zealously to eradicate it everywhere else.

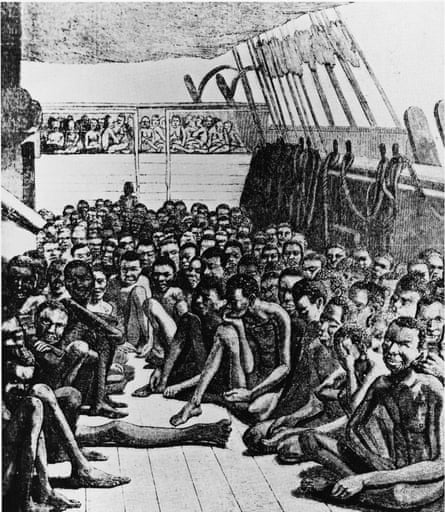

As Michael Taylor points out in his scintillating new book, this is a farrago of nonsense. Slavery was certainly an ancient practice, but for 200 years the British developed it on an unprecedented scale. Throughout the 18th century, they were the world’s foremost slavers, and the plantation system they helped create devoured the lives of millions of African men, women and children. In the name of profit and racial superiority, English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish enslavers inflicted a holocaust of suffering on their human chattels, practising rape, torture, mutilation, and manslaughter.

The cessation of the transatlantic trade in 1807 didn’t end this. It changed nothing for the 700,000 enslaved people already held captive in Britain’s West Indian colonies; soon afterwards, the British government acquired additional slave territories in South America. Slavery remained central to Britain’s economic and strategic interests, and for more than a decade and a half after 1807 almost no one campaigned to end it. As an Anglican bishop explained the Bible’s teachings, there was all the difference in the world between the sinful trafficking of kidnapped Africans and the divinely sanctioned trade in existing slaves: “buying men is not the same as stealing them”. William Gladstone, in his maiden speech as an MP in 1832, put forward a similar argument.

Meanwhile, many other countries took the lead in abolishing the practice for good. By the 1820s, slavery had been banned in the free black republic of Haiti (since 1804), in most of the northern states of the US, and throughout much of Latin America. Enslaved people across the Caribbean continued to protest against and resist their bondage. But in Britain, public opinion remained overwhelmingly comfortable with its continuance on a vast scale.

After all, the West Indies were the jewel in the British colonial system: the labour of their slaves produced immeasurable private and public wealth for Britain’s government, cities, merchants and citizens. As the nation’s greatest hero, Lord Nelson was said to have expressed it, just a few months before his death at Trafalgar, he would always be “a firm friend” to slaveholders – for “I was bred in the good old school and taught to appreciate the value of our West India possessions; and neither in the field, nor in the senate, shall their just rights be infringed, whilst I have an arm to fight in their defence, or a tongue to launch my voice against the damnable and cursed doctrine of Wilberforce, and his hypocritical allies”.

The Interest is the story of how widespread and deeply rooted such attitudes were, how powerfully calls for abolition were resisted and why the British parliament nonetheless voted at last in 1833 to end slavery in its West Indian and African territories. In 20 brisk, gripping chapters, Taylor charts the course from the foundation of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1823 to the final passage of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

Part of what makes this a compulsively readable book is his skill in cross-cutting between three groups of protagonists. On one track, we follow the abolitionist campaigners on their lengthy, uphill battle: organising local committees, writing propaganda, lobbying unsympathetic members of Parliament.

This well-known story is reanimated by some brilliant pen-portraits. Alongside Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and Zachary Macaulay, we meet such activists as the dashing abolitionist MP and barrister Stephen Lushington, fellow of All Souls and first-class cricketer, with his aquiline nose and mane of thick, black hair; and the energetic Quaker reformer Elizabeth Heyrick, who in 1824, “incandescently angry with the apparent timidity of the abolitionist leadership”, published her bestselling pamphlet Immediate, Not Gradual Emancipation, and launched an all-out “holy war” against slavery through a boycott of West Indian sugar.

A second strand illuminates the fears and bigotries of white British West Indians. The slightest prospect of ameliorating the condition of black people inevitably roused them to violence and resentment. When the British government, trying to derail abolition, made some toothless recommendations for the improved treatment of slaves, the planters were furious. “WE CANNOT BE GOVERNED BY TYRANNY”, screamed the front page of the Barbadian newspaper; across the region there was intermittent talk of proclaiming independence from Britain, or even of joining the United States.

The main focus of the book, however, is on the colonists’ powerful domestic allies, the so-called West India Interest – the countless merchants, civil servants, judges, writers, publicists, landowners, clergymen and politicians who believed that even the gradual abolition of slavery was extremist, treasonous folly, and fought tooth and nail to preserve it. Taylor paints a vivid picture of their outlook, organisation and superior political connections.

One of the book’s antiheroes is George Canning, the Tory foreign secretary and prime minister, whose commonplace racism and contempt for anti-slavery arguments were evident even when he tried to embody government evenhandedness. “I am sure you do not doubt my sincerity as to the good of the blacks,” he told Wilberforce, “but I confess I am not prepared to sacrifice all my white fellow countrymen to that object.” In another speech, he referred to Frankenstein’s monster (that “splendid fiction of a recent romance”) in warning of the dangers of emancipation: “In dealing with the negro, we must remember that we are dealing with a being possessing the form and strength of a man, but the intellect only of a child.”

Despite increasing political and economic crises, the Interest held firm for almost a decade. Then, in the space of a few months, the fortunes of abolition were transformed by two completely different forces. The first was the heroic efforts of enslaved people themselves. White fears of their unceasing resistance had already helped bring about the Slave Trade Act of 1807. Now a new uprising in Jamaica in the winter of 1831-32 (motivated, ironically enough, by slaves’ belief that parliament had already legislated abolition) bolstered the view that, without a transition to free labour, the colonies might be lost altogether. At the same time, the political earthquake of the Great Reform Act in 1832 returned, for the first time, a parliament full of avowed abolitionists. Even then, the pro-slavery King William IV only signed the 1833 Abolition Bill into law because he was assured that, in practice, emancipation was bound to fail.

The Interest never gave up. Under the terms of the act, West Indian slaves were not immediately freed, but forced to labour on for years as unpaid “apprentices”. Meanwhile, the British government compensated slaveholders generously for the loss of their human property. As a proportion of government spending, Taylor estimates they received the equivalent in today’s money of about £340bn – more than five times the combined GDPs of the modern nations of the Caribbean. He ends, appropriately, with a plea for reparatory justice and a proper reckoning by our national institutions with the enduring legacies of centuries of slavery. As this timely, sobering book reminds us, British abolition cannot be celebrated as an inevitable or precocious national triumph. It was not the end, but only the beginning.