Trending

This story is from November 16, 2020

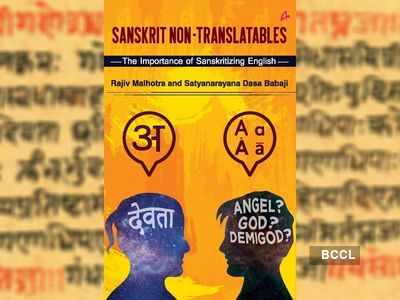

Exclusive Excerpt: 'Sanskrit Non-Translatables: The Importance of Sanskritizing English'

A new book titled, 'Sanskrit Non-Translatables: The Importance of Sanskritizing English' talks about how Sanskrit needs to be better integrated into English.

Photo:Amaryllis

Sanskrit is one of the oldest living languages today. It's responsible for shaping many modern languages and even today, as the global narrative evolves to encompass every culture and absorb into it several Indian philosophies, Sanskrit helps add to their vocabulary.

However, some might argue that Sanskrit isn't easily translatable and the translated definitions of the words don't do justice to their meanings.Translation programs might stop the usage of Sanskrit by making it redundant.

Such arguments, clarifications and more find place in a new book 'Sanskrit Non-Translatables: The Importance of Sanskritizing English' by Rajiv Malhotra and Satyanarayan Dasa. Any lover of language is sure to find this book a treasure, for its insight into the ancient language. Its translations are fascinating and by the end of the book, you will leave with your vocabulary enhanced.

The book has been published by Amaryllis, literary fiction and non-fiction imprint of Manjul Publishing House.

Diversity of Civilizations

Excerpts from Sanskrit Non-Translatables by Rajiv Malhotra and Satyanarayan Dasa

The distinctiveness of the cultural and spiritual matrix of dharma civilizations is under siege from something insidious: the widespread dismantling, rearrangement, and digestion of dharmic culture into Western frameworks, by disingenuously characterizing the latter as ‘universal’.

This process of absorption of dharmic ideas can take place with good intentions and also with the tacit cooperation of individuals immersed in dharma. They sometimes question: Why not assimilate? Aren’t we all really ‘the same’? What is incorrect about a ‘universal’ point of view? Isn’t the large-scale absorption of Indian ideas, arts, sciences, medicine, business practices and letters something positive? Isn’t it wonderful that millions of Americans and Europeans practice and propagate yoga and that Indian cuisine has gone global? Besides, doesn’t the West have something to offer India in exchange – such as scientific advances, social justice, business and political know-how? The obvious answer to all these questions would at first be a ‘Yes’.

Yet, much of what appears to be an explicit Indian influence on the West is indicative of a process that threatens to deplete the very sources of dharma on which it draws. Talk of global culture and universalism often creates the sunny impression thatthe fusion of dharmic and Western cultures is always good. This assumption ignores the many distortions and unacknowledged appropriations on the part of the West, as well as the highly destructive influences of fundamentalist Christianity, Marxism, capitalist expansionism and myopic secularism.

Global culture is bridging and blurring boundaries across races, ethnicities, nationalities and faiths. Consumerism is redefining lifestyles and aesthetics by blending universal components. The increased mobility of people, goods and capital is more likely taking us closer to a world of true meritocracy (a phenomenon that Pulitzer Prize winner, Thomas Friedman calls the ‘flat world’2), and economic and ecological integration is helping dismantle localized obstacles. The youth is especially quick to embrace new kinds of global identities, often at the expense of native traditions.

At the same time, an appreciation of the exotic, colorful and novel aspects of Indian culture appear to be on the rise, owing to the influence of Yoga, Indian cuisine, the film industry, traditional music and dance, and so on. Indian spiritual capital enjoys a pride of place in the global quest for greater well-being, as evidenced by the popularity of Yoga, meditation and Ayurvedic medicine in various forms and by the influence wielded by certain self-help guru-s in popular culture. In fact, Americans invest enormous amounts of money in alternative health and spiritual practices which are of Indian origin, whether or not they realize, or accept, the Indian root.

This leads many to conclude that the essential differences among civilizations no longer matter. Several prominent critics have blamed religious, cultural, racial and national divisions for much of the violence and fragmentation that are destabilizing the world today. They argue that all such distinctions are obsolete and primitive.

The arguments that distinct cultures should coalesce into something universal are expressed in theories that perceive ideal societies as ‘post-modern’, ‘post-racial’, ‘post-religious’ and ‘post-nationalistic’. These fashionable constructs seem to announce the arrival of a flat, secularized world that is undifferentiated by specific histories, identities and religious points of view. The anti-modernity movement of the twentieth century was one such construct; its lofty goal of rejecting Western aggression led to colonialism, genocide, two World Wars, Nazism and Communism. Anti-modernity offered little by way of a positive affirmation of differences and little understanding of why it might be valuable and desirable for differences to coexist harmoniously.

What is misleading about the ‘flat world’ assumption is that while superficial cultural elements do seem to have coalesced into a common global culture, the deeper structures that support the power and privilege of certain groups are stronger than ever before. Globalization is often framed in terms and structures that emerged under Western domination of the world over the past five hundred years or so. These in turn, are founded on the values and beliefs that emerged from the unique historical and religious experiences of the peoples of European origin. When all collective identities are discarded and all boundaries challenged – whether under the rubric of post-modern critique or as a result of a vague sense that ‘all are one’ and ‘we are all fundamentally the same’ – the result is not a world free from dominance but one in which the strongest identities along with their versions of history and values prevail.

This asymmetry of power and resources in the production and spread of a dominant narrative leads to abrasive cultural exchanges. It is only recently that China has begun responding to the Western narrative on its own terms. The Islamic world too, powered by oil-generated-wealth, is able to spread its narrative via the Western-controlled channels of knowledge legitimization. Weak cultures and civilizations will end up getting digested and rendered irrelevant in the face of this hegemonic march of history.

The Indian situation in the clash of civilizations is indeed disheartening. The Indian state was weakened to a deep state of atrophy after close to one thousand years of colonial rule and became further diluted after independence in 1947 by way of poor policies and inefficient and corrupt governing structures. It is only recently, after seventy-odd years, that the need and relevance of a truthful civilizational narrative as the basis for nation-building is being considered at the highest levels of governance. Steps, however small, are being taken to build a foundation for an India based on India’s self-narratives and its civilizational riches.

Given this reality, it is now up to the Indian peoples and those on the journey of dharma to take control of the civilizational narrative and regain the adhikara (authority) to interpret the world on their own terms. The economic prosperity over the last few decades, and the marked absence of crippling poverty has, for the most part, freed Indians to think beyond survival and mere economic progress. The quest for civilizational identity has created a hunger for dharma-based ideas, which now responds to the factually misleading and culturally corrosive narratives of the mainstream.

However, some might argue that Sanskrit isn't easily translatable and the translated definitions of the words don't do justice to their meanings.Translation programs might stop the usage of Sanskrit by making it redundant.

Such arguments, clarifications and more find place in a new book 'Sanskrit Non-Translatables: The Importance of Sanskritizing English' by Rajiv Malhotra and Satyanarayan Dasa. Any lover of language is sure to find this book a treasure, for its insight into the ancient language. Its translations are fascinating and by the end of the book, you will leave with your vocabulary enhanced.

The book has been published by Amaryllis, literary fiction and non-fiction imprint of Manjul Publishing House.

Here's an excerpt for those interested:

Diversity of Civilizations

Excerpts from Sanskrit Non-Translatables by Rajiv Malhotra and Satyanarayan Dasa

The distinctiveness of the cultural and spiritual matrix of dharma civilizations is under siege from something insidious: the widespread dismantling, rearrangement, and digestion of dharmic culture into Western frameworks, by disingenuously characterizing the latter as ‘universal’.

This process of absorption of dharmic ideas can take place with good intentions and also with the tacit cooperation of individuals immersed in dharma. They sometimes question: Why not assimilate? Aren’t we all really ‘the same’? What is incorrect about a ‘universal’ point of view? Isn’t the large-scale absorption of Indian ideas, arts, sciences, medicine, business practices and letters something positive? Isn’t it wonderful that millions of Americans and Europeans practice and propagate yoga and that Indian cuisine has gone global? Besides, doesn’t the West have something to offer India in exchange – such as scientific advances, social justice, business and political know-how? The obvious answer to all these questions would at first be a ‘Yes’.

Yet, much of what appears to be an explicit Indian influence on the West is indicative of a process that threatens to deplete the very sources of dharma on which it draws. Talk of global culture and universalism often creates the sunny impression thatthe fusion of dharmic and Western cultures is always good. This assumption ignores the many distortions and unacknowledged appropriations on the part of the West, as well as the highly destructive influences of fundamentalist Christianity, Marxism, capitalist expansionism and myopic secularism.

Global culture is bridging and blurring boundaries across races, ethnicities, nationalities and faiths. Consumerism is redefining lifestyles and aesthetics by blending universal components. The increased mobility of people, goods and capital is more likely taking us closer to a world of true meritocracy (a phenomenon that Pulitzer Prize winner, Thomas Friedman calls the ‘flat world’2), and economic and ecological integration is helping dismantle localized obstacles. The youth is especially quick to embrace new kinds of global identities, often at the expense of native traditions.

At the same time, an appreciation of the exotic, colorful and novel aspects of Indian culture appear to be on the rise, owing to the influence of Yoga, Indian cuisine, the film industry, traditional music and dance, and so on. Indian spiritual capital enjoys a pride of place in the global quest for greater well-being, as evidenced by the popularity of Yoga, meditation and Ayurvedic medicine in various forms and by the influence wielded by certain self-help guru-s in popular culture. In fact, Americans invest enormous amounts of money in alternative health and spiritual practices which are of Indian origin, whether or not they realize, or accept, the Indian root.

This leads many to conclude that the essential differences among civilizations no longer matter. Several prominent critics have blamed religious, cultural, racial and national divisions for much of the violence and fragmentation that are destabilizing the world today. They argue that all such distinctions are obsolete and primitive.

The arguments that distinct cultures should coalesce into something universal are expressed in theories that perceive ideal societies as ‘post-modern’, ‘post-racial’, ‘post-religious’ and ‘post-nationalistic’. These fashionable constructs seem to announce the arrival of a flat, secularized world that is undifferentiated by specific histories, identities and religious points of view. The anti-modernity movement of the twentieth century was one such construct; its lofty goal of rejecting Western aggression led to colonialism, genocide, two World Wars, Nazism and Communism. Anti-modernity offered little by way of a positive affirmation of differences and little understanding of why it might be valuable and desirable for differences to coexist harmoniously.

What is misleading about the ‘flat world’ assumption is that while superficial cultural elements do seem to have coalesced into a common global culture, the deeper structures that support the power and privilege of certain groups are stronger than ever before. Globalization is often framed in terms and structures that emerged under Western domination of the world over the past five hundred years or so. These in turn, are founded on the values and beliefs that emerged from the unique historical and religious experiences of the peoples of European origin. When all collective identities are discarded and all boundaries challenged – whether under the rubric of post-modern critique or as a result of a vague sense that ‘all are one’ and ‘we are all fundamentally the same’ – the result is not a world free from dominance but one in which the strongest identities along with their versions of history and values prevail.

This asymmetry of power and resources in the production and spread of a dominant narrative leads to abrasive cultural exchanges. It is only recently that China has begun responding to the Western narrative on its own terms. The Islamic world too, powered by oil-generated-wealth, is able to spread its narrative via the Western-controlled channels of knowledge legitimization. Weak cultures and civilizations will end up getting digested and rendered irrelevant in the face of this hegemonic march of history.

The Indian situation in the clash of civilizations is indeed disheartening. The Indian state was weakened to a deep state of atrophy after close to one thousand years of colonial rule and became further diluted after independence in 1947 by way of poor policies and inefficient and corrupt governing structures. It is only recently, after seventy-odd years, that the need and relevance of a truthful civilizational narrative as the basis for nation-building is being considered at the highest levels of governance. Steps, however small, are being taken to build a foundation for an India based on India’s self-narratives and its civilizational riches.

Given this reality, it is now up to the Indian peoples and those on the journey of dharma to take control of the civilizational narrative and regain the adhikara (authority) to interpret the world on their own terms. The economic prosperity over the last few decades, and the marked absence of crippling poverty has, for the most part, freed Indians to think beyond survival and mere economic progress. The quest for civilizational identity has created a hunger for dharma-based ideas, which now responds to the factually misleading and culturally corrosive narratives of the mainstream.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA