- India

- International

New Vivekananda statue at JNU demands obedience and piety rather than engagement

The installation of the statue comes as its obverse, of a theatre of power heralding a new reality, presided over by the Prime Minister himself at his alliterative best (invoking “confidence, conviction, character”).

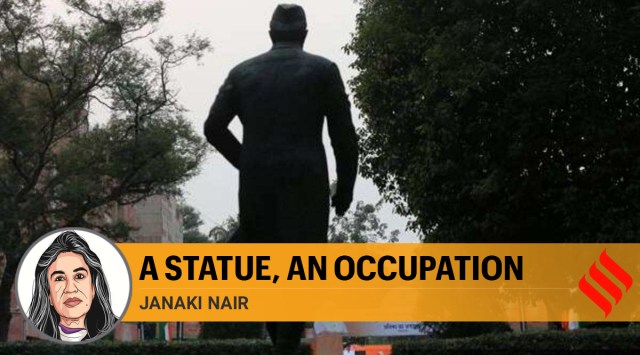

The Vivekananda statue at JNU (Express photo/Tashi Tobgyal)

The Vivekananda statue at JNU (Express photo/Tashi Tobgyal) No Indian city is exempt from the competitive assertion of rights to public spaces by hitherto dominated groups. Statues and flagpoles at street corners serve as a reminder of new urban collectivities, of auto drivers and their cinematic heroes, of Dalits and their radical political forebears, of poets who remind us of a rich linguistic and cultural heritage. They announce a new political presence in a segmented and hierarchical public arena, but dominant groups and ideologies are not far behind in “occupying” space with sometimes gigantic symbols of power. This rich economy of symbols is an inseparable part of our public life.

The need to install and unveil a statue of Vivekananda at the JNU campus came from such symbolics of “occupation”. As his tumultuous term as vice-chancellor (VC) of the prestigious university comes to a close, will Mamidala Jagdish Kumar look back with satisfaction at having not only undermined almost all the statutes of this institution but “occupying” it with a statue and flags? Flanking the entrance to the administration block, the statue had been under (saffron) wraps for well over two years, before being finally unveiled on November 12.

Kumar engaged with the symbolics of “occupation” throughout his tenure. He mounted, in 2017, a Wall of Heroes to 21 decorated soldiers, making JNU the first university to comply with the ministry of human resources and development (MHRD)’s “Vidya Veerta Abhiyan”. In the name of restoring purportedly “defaced” walls, he wiped clean JNU’s magnificent mural art. And in response to the illuminating discussions on nationalism that JNU teachers mounted in the turbulent months after February 2016, Kumar asked for a tank to be rolled on to the campus to “instil” nationalism. A statue may not have the looming bulk of a tank, but it serves several purposes – of planting a flag in “enemy” territory, and sacralising it.

Explained | The row over the Vivekananda statue that PM Modi unveiled at JNU

JNU had long nurtured the tradition of a social realism that engaged with contemporary and historical issues in its expressive mural traditions, heartfelt songs and theatrical productions. The installation of the statue comes as its obverse, of a theatre of power heralding a new reality, presided over by the Prime Minister himself at his alliterative best (invoking “confidence, conviction, character”). Who better than Vivekananda, repurposed as the poster boy of the Hindu right, to be at the centre of this occupation game? So, we only recently learned that the statue, whose provenance was shrouded both literally and figuratively, was proposed by an alumnus, Manoj Kumar, to the VC for its “pleasing look”, funded by one Vipul Patel in the US, and executed by one Naresh Kumawat.

It bears all the marks of a brazen “occupation”, and like our former British rulers who implanted statue politics in our midst, makes a very literal point of triumphing over the “enemy”. Here the “enemy” is Jawaharlal Nehru, whose statue was publicly sculpted by the renowned artist Biman Das in 2004-05, in an atelier just below the administration block. There was nothing mysterious about its making. Anil Bhatti, in his contribution to our forthcoming book titled JNU Stories: The First Fifty Years, has this to say: “The statue is, of course, a statement. But it is different from the statues in other universities because of this oblique, eccentric location slightly off-centre with the age-old Aravalli rocks behind it. And because the motto at the base of the statue itself gives the construction an emblematic structure demanding interpretation.”

Nothing could be a starker contrast to the Nehru statue than the new outcrop on the JNU horizon. Its furtive existence was enhanced by its prolonged shrouding in tattered orange cloth. By positioning the statue squarely at the entrance to the administration block, by purposely making it “three feet taller” than the Nehru sculpture, and, above all, by sacralising it, the stolid but domineering Vivekananda is a symbol of all that the university has become over the last five years. Unencumbered by any commitment to critical reason, to connecting past and present, it demands obedience and piety rather than engagement.

Are we being thrown back to a worshipful past, or to a time before the messy but exhilarating democracy and the opportunities it has offered to reconfigure the university? Or are we invited to engage with the Vivekananda who saw through “sectarianism, bigotry, and its horrible descendant, fanaticism”, which had “filled the earth with violence, drenched it often with human blood, destroyed civilisation and sent whole nations to despair?” The one who railed against any one religion claiming to be self-sufficient, and therefore denouncing any claim to religious superiority of any kind?

The strategy of “occupation” allows only for a pious engagement. We are no wiser about what Vivekananda had imagined higher education would become in independent India, or about what he would have thought of the plural, inclusive, and yet questioning space that the Indian public university has already become. His call to “manliness” as a gospel of our times would be grotesquely inappropriate given the unbridled and entitled masculinity that is now on display in most parts of India. We are already thrown into the already overheated mythology around Vivekananda, including videos — entitled “Real Voice of Swami Vivekananda”, “The Original Voice of Swami Vivekananda”, etc, — claiming to purvey the original voice of Swami Vivekananda. (The unfortunate popularity of these fakes led the Ramakrishna Math and Mission to issue a clarification that “there is no voice recording of Swami Vivekananda, let alone of his speeches at the World’s Parliament of Religions, available to us today”.)

Which Vivekananda is at stake? But, above all, whose university is at stake? Fervid cries to change the name of JNU have already begun. Thankfully, opposition to such change has come from the ABVP, fearful of what might be thrown out with the bathwater: The great reputation of a university to which they yearn to belong, but cannot, alas, build.

This article first appeared in the print edition on November 27, 2020, under the title ‘A statue, an occupation’ The writer is former professor of history, JNU

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05