Kolkata — Despite objections by a majority of the panel members, a committee of the Reserve Bank of India has recommended that large corporate entities be allowed to set up banks.

The recommendations drew immediate criticism, with the former governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and its former deputy head calling the key proposal “a bombshell.”

“While the proposal is tempered with many caveats, it raises an important question: Why now? Have we learnt something that allows us to override all the prior cautions on allowing industrial houses into banking? We would argue no. Indeed, to the contrary, it is even more important today to stick to the tried and tested limits on corporate involvement in banking,” Raghuram Rajan, the former governor of the RBI, and Viral Acharya, the former deputy governor, wrote in a three-page-article posted on LinkedIn.

“In sum, many of the technical rationalizations proposed by the Internal Working Group are worth adopting, while its main recommendation — to allow Indian corporate houses into banking — is best to be left on the shelf,” they wrote.

Rajan and Acharya, since their departures from the RBI, have raised questions about the central bank, including the erosion of its autonomy and the overall health of the banking sector.

Apart from their objections, “All the experts except one were of the opinion that large corporate/industrial houses should not be allowed to promote a bank,” the central bank’s Internal Working Group report itself states. “The main reason being the prevailing corporate governance culture in corporate houses is not up to the international standard and it will be difficult to ring-fence the non-financial activities of the promoters with that of the bank.”

Other objections to the recommendations came from a range of critics, including Standard & Poors Global Ratings.

“The working group’s concerns regarding conflict of interest, the concentration of economic power, and financial stability in allowing corporates to own banks are potential risks,” S&P Global Ratings said in a note.

India economist Jean Drèze told Zenger News, “I am broadly in agreement with the concerns expressed by Raghuram Rajan and Viral Acharya in their excellent rejoinder. Allowing corporate entities to own banks would create a dangerous conflict of interest. There are other important warnings in that rejoinder, for those who read between the lines.”

Drèze played a key role in the drafting the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act in 2005, aimed at providing social and job security to marginalized populations.

“In the past, people have been careful not to allow financial institutions becoming too large or free because they can distort the structure of the whole economy and favor those who have more money,” Arun Maira, a management consultant and former member of Planning Commission of India, told Zenger News.

The recommendations put forth by the Internal Working Group on Nov. 20 reviewed ownership guidelines and corporate structure for private sector banks in India.

“Well run large non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), with an asset size of ₹50,000 crore ($677 million) and above, including those which are owned by a corporate house, may be considered for conversion into banks subject to completion of 10 years of operations and meeting due diligence criteria and compliance with additional conditions specified in this regard,” the recommendations state.

NBFCs grant loans and advances, and may acquire shares/stocks/bonds/debentures/securities issued by the government or local authority, but they do not have a full banking license.

“India certainly needs more banks,” said Umesh Revankar, managing director of Shriram Transport Finance. “Both banks and non-banking financial companies need to coexist. The latter serve the interest of the under-banked. If they become banks, they will be restricted by Reserve Bank of India’s regulations.”

Revankar said interest rates and the margins of NBFCs need to be lowered.

“Ultimately, we need to look into the welfare of our shareholders, employees as well as customers,” he said.

Many Indian corporate houses or groups, including Bajaj, Tata, Piramal, Aditya Birla and L&T, own non-banking financial companies. A majority of these companies are not allowed to accept public deposits in India.

One of the aims of the Internal Working Group was to bring more efficiency to the banking sector, which has been moving toward consolidation. One of the biggest consolidations in the public sector banking space occurred in April, when 10 banks, some dating to the pre-independence era, merged into four public sector banks to reduce operational costs and roll over the pile of bad debts.

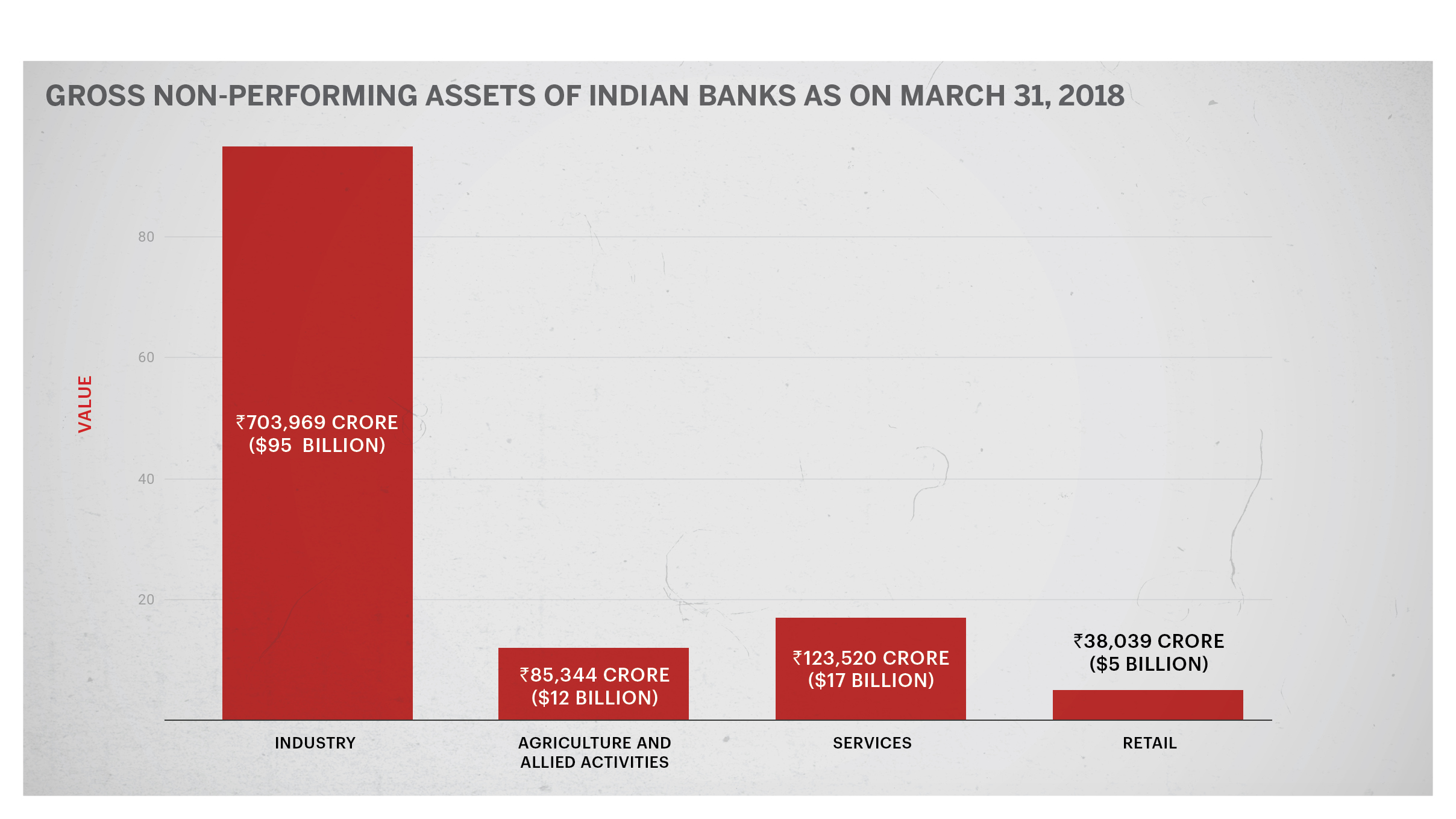

India’s public sector banks had INR 6.8 trillion ($93 billion) worth of nonperforming assets in March, according to data from Statista.

Recently, the central bank bailed out Lakshmi Vilas Bank, a Tamil Nadu-based private bank, by facilitating its merger with Singapore-based DBS Bank. In September, the shareholders of Lakshmi Vilas Bank and Kerala-based Dhanlaxmi Bank ousted their chief executive officers, citing mismanagement and concerns about the safety of depositors’ money.

In March, the central bank superseded the board of a private sector bank, YES Bank, and installed a new board, after its founder was arrested on charges of money laundering.

The total bad loans or non-performing assets of Indian banks as of March 2018 was INR 9.62 trillion ($129 billion). Of this, NR 7.04 trillion ($95 billion) were in default to Indian corporate houses or industries.

Rajan and Acharya wrote: “First, the industrial houses need financing. They can get it easily, with no questions asked if they have an in-house bank.”

Allowing private entities to set up banks has multiple risks, including connected lending, in which the promoter of the bank is also a borrower.

“The history of such connected lending is invariably disastrous. How can the bank make good loans when it is owned by the borrower?” Rajan and Archarya wrote.

In connected lending, it is possible for the promoter to channel depositors’ money into their own ventures. This might pose less risk for NBFCs backed by large corporate entities, but greater risk for banks that hold the public’s money.

Rajan and Archarya also pointed out concerns about the concentration of wealth and power if corporate entities are licensed as banks.

“Highly indebted and politically connected business houses will have the greatest incentive and ability to push for licenses. That will increase the importance of money power yet more in our politics, and make us more likely to succumb to authoritarian cronyism,” they wrote in their article posted on LinkedIn.

“In fact,” Maira said, “the more efficient the banking system becomes, the more power goes to the hands of those who own these banks. They might necessarily represent the broader public interest, but that of the shareholders. The judging of efficiency of the banks on the basis of how much shareholder value will they create is a zoomed-in view of judging the merit of a policy.”

(Edited by Siddharthya Roy and Judith Isacoff. Graph by Urvashi Makwana.)

The post India’s Central Bank Ignores Panel of Experts, Proposes Allowing Corporate Banks appeared first on Zenger News.