- News

- City News

- mumbai News

- Mumbai: Return-of-property pleas arduous and expensive

Trending

This story is from December 1, 2020

Mumbai: Return-of-property pleas arduous and expensive

When Malabar Hill resident Paresh Mehta requested a magistrate court to return his wife’s Rs 50 lakh worth diamond earrings stolen from their home and recovered by police, he had to furnish a surety of Rs 1 lakh and an indemnity bond of Rs 50 lakh.

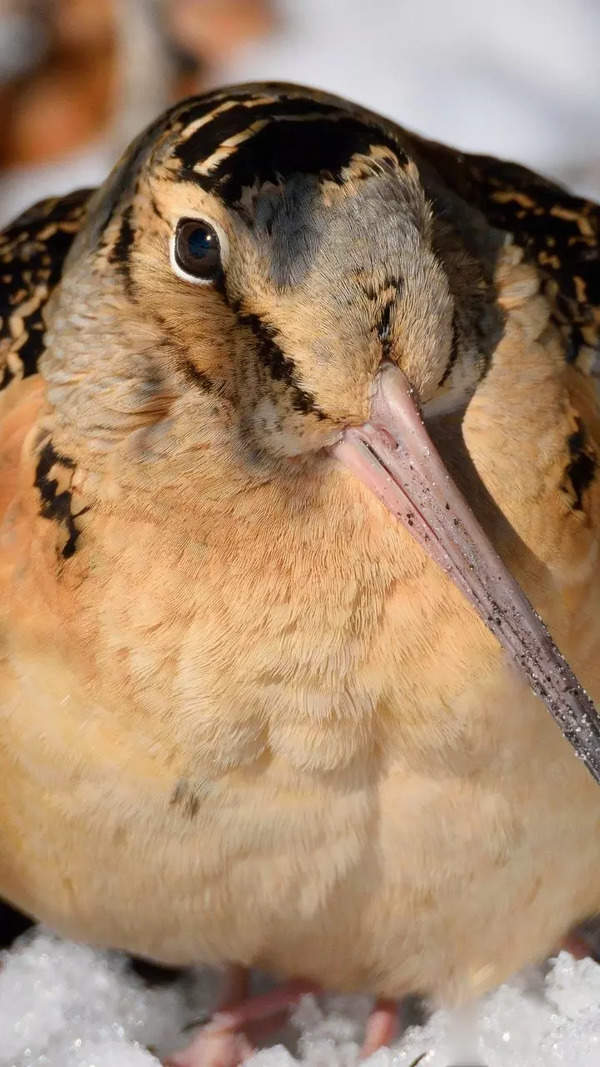

The body of a woman was found inside a trolley bag at CSMT. The bag is now part of the evidence for the trial

When Malabar Hill resident Paresh Mehta requested a magistrate court to return his wife’s Rs 50 lakh worth diamond earrings stolen from their home and recovered by police, he had to furnish a surety of Rs 1 lakh and an indemnity bond of Rs 50 lakh.

Lawyer Janhavi Gadkar, out on bail after being booked in an alleged drunk driving incident that killed two, had to furnish a similar bond of Rs 25 lakh to reclaim her Audi.

Daily, scores of suspects and victims file “return of property” pleas to reclaim items seized from crime scenes or recovered during a probe. The bonds they execute serve as security against which seized articles are released. In most cases, they cannot be disposed until end of trial and have to be produced when called for by the court. Essentially, solving of a crime or recovery of stolen goods could be merely the first step in a long process to retrieve one’s property.

In 2016, Zaibunnisa Sayed whose husband Sayed Mustafa was killed in a road accident allegedly caused by a rash driver, sought permission of the sessions court hearing the case to sell off his damaged taxi. She said it was reduced to scrap in the accident and could not be repaired. The plea was granted – it was one of those rare instances in which a court allowed an article or goods seized during a probe to be disposed of before the trial concluded.

Items which form pieces of material evidence in criminal cases or are required to be identified in a trial are often kept in custody until the verdict. This is regarded as useful in case there are multiple claimants for the same article in future. In Zaibunissa’s case, the court directed cops to take pictures of the vehicle, have it authenticated and certified and also prepare a detailed panchanama so. It said these could be used as evidence.

While returning properties, courts usually reason that if the articles are left unused for prolonged periods there’s possibility of damage. In October, a court allowed the release of a bike seized by Bandra police after its owner was booked for violating lockdown norms. Directing the offender to execute a bond of Rs one lakh, the court said the vehicle may get damaged if it stayed idle for long. “Considering the present pandemic situation, the vehicle may be released in favour of the applicant.”

While jewellery, cars and phones are obvious items that most would want to reclaim, television sets, printers, air conditioners and even clothes are frequently claimed. Agripada-based Yogesh Thakkar had to furnish a bond of Rs 8,500 for five pairs of jeans, an old pair of trousers and shirt, and a mobile stolen from his home earlier this year.

The process can be arduous. In a recent case, a Sewri family miraculously managed to get back stolen jewellery worth Rs 5 lakh four days after their house was broken into. Robbers threw the loot back into the house after a complaint was filed. The family’s joy was however shortlived as police took away the valuables and told the victims to claim it from the court.

A Chembur resident whose iPhone was found by cops three months after it was stolen in August 2017, took an additional two weeks to finally get his hands on it. After identifying his phone at the police station, the 27-year-old had to hire a lawyer and make an application before the magistrate’s court. “The entire procedure could have been much easier if it had taken place at the police station itself. It took three court dates to get my phone back. The first was when the application was submitted, second when the matter was heard and decided with cops filing a reply and third when I furnished the indemnity bond. While the lawyer’s fees was around Rs 5,000, I had to furnish an indemnity bond of Rs 15,000 for the two-year-old phone,” he said.

Disposing items despite the court’s riders can invite legal trouble as in the case of Ramadhar Rajbhar, father of a murder accused, Vijay Rajbhar, who recently told the trial court that the tempo purportedly used to dispose of the bodies of the two victims had been sold. In 2016, while allowing his plea for return of property, the court said he was not to dispose the vehicle. Last week the court issued a bailable warrant against Ramadhar after he failed to be present and produce the vehicle. He could now forfeit Rs five lakh he had executed as an indemnity bond.

Lawyer Janhavi Gadkar, out on bail after being booked in an alleged drunk driving incident that killed two, had to furnish a similar bond of Rs 25 lakh to reclaim her Audi.

Daily, scores of suspects and victims file “return of property” pleas to reclaim items seized from crime scenes or recovered during a probe. The bonds they execute serve as security against which seized articles are released. In most cases, they cannot be disposed until end of trial and have to be produced when called for by the court. Essentially, solving of a crime or recovery of stolen goods could be merely the first step in a long process to retrieve one’s property.

Property seized in crimes can elude owners for years

In 2016, Zaibunnisa Sayed whose husband Sayed Mustafa was killed in a road accident allegedly caused by a rash driver, sought permission of the sessions court hearing the case to sell off his damaged taxi. She said it was reduced to scrap in the accident and could not be repaired. The plea was granted – it was one of those rare instances in which a court allowed an article or goods seized during a probe to be disposed of before the trial concluded.

Items which form pieces of material evidence in criminal cases or are required to be identified in a trial are often kept in custody until the verdict. This is regarded as useful in case there are multiple claimants for the same article in future. In Zaibunissa’s case, the court directed cops to take pictures of the vehicle, have it authenticated and certified and also prepare a detailed panchanama so. It said these could be used as evidence.

While returning properties, courts usually reason that if the articles are left unused for prolonged periods there’s possibility of damage. In October, a court allowed the release of a bike seized by Bandra police after its owner was booked for violating lockdown norms. Directing the offender to execute a bond of Rs one lakh, the court said the vehicle may get damaged if it stayed idle for long. “Considering the present pandemic situation, the vehicle may be released in favour of the applicant.”

While jewellery, cars and phones are obvious items that most would want to reclaim, television sets, printers, air conditioners and even clothes are frequently claimed. Agripada-based Yogesh Thakkar had to furnish a bond of Rs 8,500 for five pairs of jeans, an old pair of trousers and shirt, and a mobile stolen from his home earlier this year.

The process can be arduous. In a recent case, a Sewri family miraculously managed to get back stolen jewellery worth Rs 5 lakh four days after their house was broken into. Robbers threw the loot back into the house after a complaint was filed. The family’s joy was however shortlived as police took away the valuables and told the victims to claim it from the court.

A Chembur resident whose iPhone was found by cops three months after it was stolen in August 2017, took an additional two weeks to finally get his hands on it. After identifying his phone at the police station, the 27-year-old had to hire a lawyer and make an application before the magistrate’s court. “The entire procedure could have been much easier if it had taken place at the police station itself. It took three court dates to get my phone back. The first was when the application was submitted, second when the matter was heard and decided with cops filing a reply and third when I furnished the indemnity bond. While the lawyer’s fees was around Rs 5,000, I had to furnish an indemnity bond of Rs 15,000 for the two-year-old phone,” he said.

Disposing items despite the court’s riders can invite legal trouble as in the case of Ramadhar Rajbhar, father of a murder accused, Vijay Rajbhar, who recently told the trial court that the tempo purportedly used to dispose of the bodies of the two victims had been sold. In 2016, while allowing his plea for return of property, the court said he was not to dispose the vehicle. Last week the court issued a bailable warrant against Ramadhar after he failed to be present and produce the vehicle. He could now forfeit Rs five lakh he had executed as an indemnity bond.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA