This reporter went to cover a homicide in Mexico. Then he became a victim

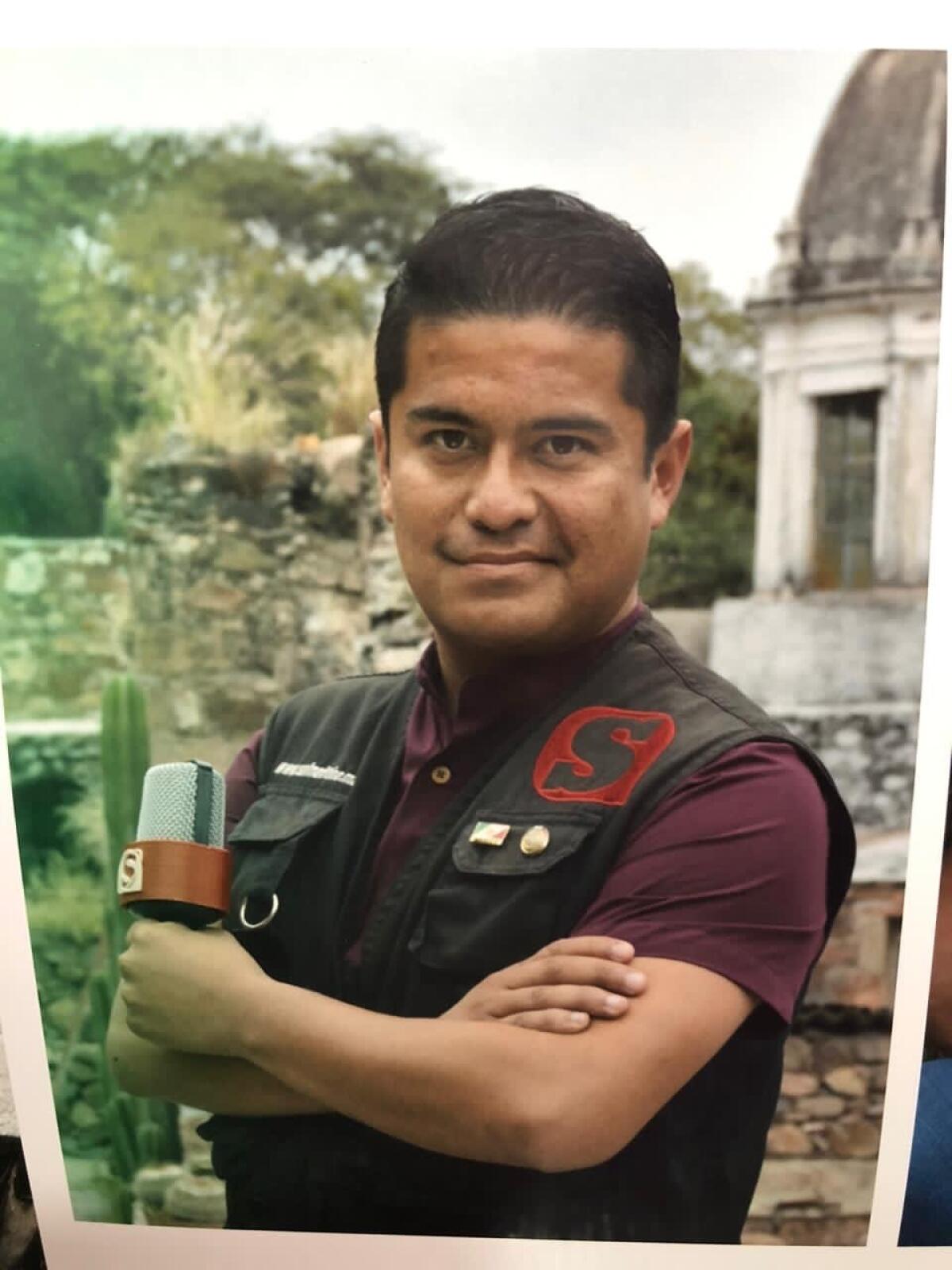

Israel Vázquez Rangel, a veteran reporter for an online news outlet in central Guanajuato state, is gunned down by two men on a motorcycle.

Homicides are so unremarkable in some parts of Mexico that police are in no rush to respond. The news media often beat them to grisly crime scenes.

That’s what went down recently with Israel Vázquez Rangel, an ace reporter for an online news outlet in the central state of Guanajuato. Tipster calls sent him in the predawn darkness of Nov. 9 to a macabre sight: a street strewn with plastic bags stuffed with body parts, along with a severed head in a bucket.

The spectacle is not unusual in Guanajuato, a battleground for rival gangs that exult in flaunting payback against rivals. Vázquez, a 31-year-old veteran of the cop beat, had seen it all before.

But this assignment ended up being his last. A story he never got to file.

::

A native of Salamanca, a gritty petrochemical hub nearly 160 miles northwest of Mexico City, Vázquez studied communications in college and followed the path of two elder siblings into journalism.

“Israel was always very enthusiastic, ready to learn, always staying late to find out more information,” said Jesús Padilla, an editor of the newspaper am, where Vázquez began his career. “He was a go-getter.”

Widely known by the diminutive Isra, he was animated about soccer and a committed fan of the professional Club León who covered the sport fervently. He would eventually develop another specialty — crime reporting.

Crime journalists in Mexico are a singular breed. Typically from working-class backgrounds, they’re adrenaline-driven, digital-age throwbacks to the days of Weegee, the 20th century chronicler of the New York underworld.

These newshounds scrutinize social media, work police sources and follow tips, often speeding to crime scenes on motorcycles. They vie for scoops, but also pool leads with colleagues in the close-knit fraternity. They walk a fine line, sometimes withholding details in reports — such as the names of gangs suspected in killings — so as to not inflame those inclined to seek revenge against the news media.

Vázquez was aggressive, flashed a wide smile and seemed to get along with most everyone — victims, witnesses, cops, politicians. Whether the topic was crime, soccer or the downtrodden, his on-scene dispatches made him a local celebrity, the charismatic face of the news site El Salmantino.

“It was a total chaos,” Vázquez said in a Facebook Live broadcast in September, recalling the latest gang attack on a Salamanca market where hitmen regularly target merchants who rebuff shakedowns.

“People were running around asking what was happening. You could hear the ambulance and more police cars arriving. Cops with rifles were running. People were yelling that other shop owners had been killed. Others said a shootout was raging.”

The crime beat is known as la nota roja, the red story. The lurid details guarantee web hits in an era of intensified competition and dwindling advertising revenue. But documenting the mayhem is among the riskiest assignments.

Since 2010, at least 81 journalists have been slain in Mexico, making it one of the most dangerous countries for the news media, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, a New York-based advocacy group. Many of the victims, if not most, reported on crime and links between gangs and corrupt police or lawmakers.

Three years ago, Vázquez jumped to El Salmantino, known for its aggressive coverage of Salamanca and for not bowing to the corrupt political class. One of its signatures is Facebook Live reports, often from crime venues, filed by cellphone. The site’s Facebook page has more than 400,000 followers — 120,000 more than the population of the city.

His move coincided with a major shift in the news in Guanajuato state, from quiet industrial hub and tourist destination to hotbed of violence.

“More and more, crime was the story,” said Victor Ortega, editor of El Salmantino. “And Isra became very good at it.”

Vázquez went beyond reporting the basic facts. When tightly wrapped plastic bundles were dumped on several major streets in early November — the way gangs often dispose of bodies — Vázquez could not hide his indignation after the bags turned out to be filled with trash.

He called the episode “a bad joke” and concluded: “To normalize violence and pay homage to crime is something that shouldn’t happen.”

::

Home to 5.8 million people, Guanajuato is Mexico’s sixth most populous state — but it leads in homicides, with 3,821 in the first 10 months of this year, already surpassing the record-breaking total for all of 2019. The news media record a daily litany of butchery — massacres in bars and drug-rehab facilities, abductions, shootouts, armed robberies.

In October, authorities discovered secret graves containing the remains of more than 60 people, probably kidnap victims, in the municipality of Salvatierra.

Vázquez trolled for material on the streets of Salamanca, a locus for extortion, kidnapping and gasoline theft from the behemoth state-owned Pemex refinery, which emits a 24-hour gas flare over the town. Meantime, to help make ends meet, he kept his part-time gig on the refinery’s maintenance team.

He had little free time between working his two jobs, caring for his two preteen daughters and playing for his beloved amateur soccer team, El Tigre. Separated from his wife, he also had a girlfriend — another crime reporter at El Salmantino. The two often teamed up on stories.

Driving the crime wave in Guanajuato is an unforgiving turf war between two cartels. Santa Rosa de Lima got its start stealing fuel by tapping into gas lines but has since branched out to other rackets. Its rival is the Jalisco New Generation, a sprawling syndicate that uses Guanajuato as a strategic inland corridor for moving U.S.-bound synthetic drugs from Pacific ports to the border.

The escalating turmoil is inextricably linked to criminal gangs and officials on mob payrolls.

“The violence in Guanajuato would not have reached such extremes if the governments had not given help and protection,” Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador told reporters last month. “Criminal groups are deeply rooted, and there is much collusion with authorities.”

On occasion a sense of outrage crept into Vázquez’s crime dispatches — as in September, after the mayor of Salamanca bemoaned to a TV news crew from Spain that residents weren’t doing enough to help reduce rampant lawlessness.

“What more do you want from us?” Vázquez pleaded in a Facebook Live report, noting that complaints about crime routinely went nowhere. “The citizens are demanding, more than anything else, that you provide security.”

On Nov. 8, Vázquez filed three stories — two about soccer and one about a butchered corpse discarded on a street in front of a church. He also posted a 15-minute video on the plight of a disabled street vendor, Don Horacio, who peddles chocolates to passing motorists, but had seen business decline precipitously due to the pandemic.

“I try to make a living in an honest, noble way,” Don Horacio, a father of two, recounted to Vázquez as traffic sped by on a busy boulevard. “Being disabled is a challenge that God presents to us.”

Vázquez was on duty before daybreak the next morning when calls began streaming in to El Salmantino’s tip lines. Someone had left body parts on the central thoroughfare of Fraccionamiento Villa Salamanca 400, a lawless barrio on the city’s southeastern periphery. Residents routinely alert the news site instead of dialing 911.

Vázquez got into his car, a white Nissan sedan with El Salmantino emblazoned in black and red lettering on the hood. He arrived at the site, on a dreary street of one-story concrete dwellings, shortly after 6 a.m. It was still dark and chilly. He parked his car a few yards away from the remains and approached on foot. A jacket covered his black journalist vest.

For safety, the protocol is for reporters to await the arrival of police, ambulances or colleagues before approaching crime scenes. But Vázquez decided to begin reporting what would be an exclusive. He prepared to broadcast live.

Two men on a motorcycle approached. They were probably halcónes, or gang lookouts.

Then they opened fire, hitting Vázquez at least five times. Police showed up at 6:12 a.m. to find the gravely wounded reporter lying in the street. A shaken colleague reported live as Vázquez was loaded into a Red Cross ambulance.

He arrived at the hospital at 6:57 a.m. He was pronounced dead on the operating table five hours later.

::

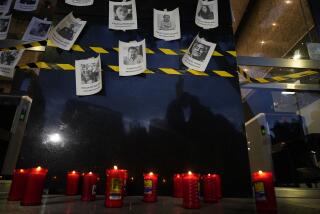

The next day, journalists gathered in protest outside City Hall in Salamanca. They brandished banners demanding “Justicia Para Israel” and declaring “Basta!” — Enough!

It wasn’t just Vázquez’s case spurring their ire.

Eight days before Vásquez was gunned down, Víctor Jiménez, 38, an online crime reporter from the nearby city of Celaya, disappeared after leaving his home en route to a baseball game.

In a meeting with the press corps, Salamanca Mayor Beatriz Hernández suggested that Vázquez was at fault for having approached the crime scene before police arrived.

“We are journalists!” outraged reporters shouted in unison.

The mayor’s comments sparked indignation in a country where officials routinely insinuate that crime victims are somehow responsible for their fates. “This argument is like saying, ‘Well, they raped her because she wore a miniskirt,’ “ Yuriria Sierra, a host for the Imagen TV network, told viewers.

Vázquez was the third Mexican journalist killed in an 11-day span, the fourth in two months and at least the eighth this year.

A TV host was ambushed and shot 10 times in Ciudad Juárez. A reporter covering crime and security for online outlets was shot dead while riding his motorcycle in the northern state of Sonora. And a crime-beat journalist for the Diario El Mundo newspaper in the gulf state of Veracruz was found beheaded, his remains dumped on train tracks.

Investigators have not said publicly if they suspect that Vázquez was killed because he was a journalist, or for some other motive. His editor said he knew of no recent threats against him.

One theory is that the gunmen mistook Vázquez for a confederate of the dismembered victim.

On Nov. 15, authorities said two suspects, presumed gang hitmen, had been arrested in connection with Vásquez’s slaying. Police identified them only as Martín “N” and José “N” and provided no other details.

But colleagues have reason to be skeptical.

Mexican authorities fail to find perpetrators in about 90% of homicides, according to Impunity Zero, a human rights group that tracks cases.

And the relatively few arrests in the cases of slain journalists typically involve the apprehensions of contract killers known as sicarios — not the crime bosses or corrupt officials who dial up hits and pay the gunmen.

For the five-person staff at El Salmantino, the slaying has been a blow of existential dimensions. Employees are receiving psychological counseling while trying to keep up with the news — since Vázquez’s death, more than a dozen killings have occurred in the same vicinity.

Meantime, with income flagging, El Salmantino is sponsoring a public raffle: Takers buy a ticket for about $15 for a chance at a new Volkswagen sedan.

“We’ve reported diligently on the murders, the extortion, the kidnappings targeting citizens, but now the statistics are hitting home for us personally,” said Ortega, the editor. “We must now analyze closely what we must do to keep on going, to endure.”

Before he was buried, relatives transported Vázquez’s remains to the soccer pitch where he played for El Tigre. Draping his coffin was his green jersey — “Isra” splashed beneath the number 13. A teammate rolled a soccer ball onto the side of the casket. As the ball ricocheted into the goal, mourners broke into final cheers for an indefatigable chronicler of daily life, and death, in his hometown.

Special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.