- India

- International

The N Guruprasad Interview: ‘Only by knowing where not to play, one would know exactly where to play’

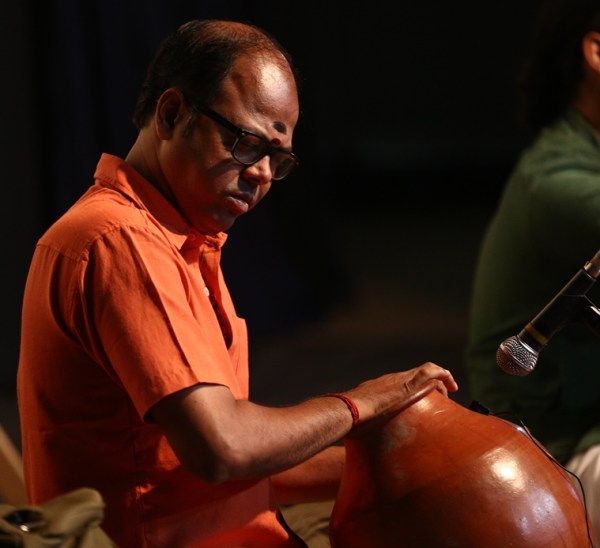

On the concert stage, Guruprasad is a delight to watch, not just for his art, but also for his elegant presence. He looks minimalist and effortless in his art, but what comes out of his humble claypot is sheer poetry.

With “Made in Manamadurai” claypot, N Guruprasad has travelled the world, performed in countless venues, collaborated with a number of national and international musicians, and is a winner of many national and regional awards. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

With “Made in Manamadurai” claypot, N Guruprasad has travelled the world, performed in countless venues, collaborated with a number of national and international musicians, and is a winner of many national and regional awards. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)For the last several years, N Guruprasad has almost been like a regular fixture in Carnatic concerts of Chennai artistes in and out of India, no matter how big or small he/she is. Probably, there isn’t a single vocalist or solo instrumentalist of some standing that he hasn’t played with. Whether it’s a big star or an upcoming artiste, whether it’s a ramshackle stage in a small temple or a big venue such as the Music Academy, whether it’s Chennai or the Oval Cricket Ground, it’s highly likely that you have seen his stoic presence on stage and attractive wizardry on a clay pot called the ghatam.

Ghatam is an inseparable part of the percussion ensemble in Carnatic music. As a sub-accompaniment to the mridangam, it makes the rhythms in Carnatic concerts fuller, more colourful and varied. When played by masters, it also elevates the overall laya of a concert besides adding a lilting swing with its crisp, intriguing sound and rhythmic formations. However, what’s interesting is that unlike the mridangam, it’s hard to see the finer details of what exactly a ghatam player is doing on the instrument other than his flying fingers, smashing strokes by the palm, and sometimes even some contortions of the belly. It’s an “instrument” that has travelled the world, not just with Carnatic music, but also with crossover forms. It has also been at the centre of Indo-Western fusion that has been identified with Indian legends such as Pandit Ravi Shankar, Mandolin Srinivas, Alla Rakha and Zakir Hussain since the 1970s, thanks to the legendary ghatam player and rhythm innovator Vikku Vinayakram (TH Vinayakram).

Despite his his percussion having a composite of diverse styles, traditions, techniques and aesthetics, N Guruprasad formally belongs to what is known as the “Thanjavur Bani”. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

Despite his his percussion having a composite of diverse styles, traditions, techniques and aesthetics, N Guruprasad formally belongs to what is known as the “Thanjavur Bani”. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

Guruprasad belongs to the same school as Vinayakram. Although his father, K Nagaraja Rao, was a famous ghatam player of his times, the young Guruprasad was sent to Vinayakram after the foundational training at home. Rao thought that he might get lenient on his son in discipline and hence wanted him to be trained by some other Guru. Under Vinayakram, who was a global celebrity, Guruprasad came to his own. He started playing in small percussion concerts with Vinayakram and his other disciples, and was soon seen on regular concert stages. Since then, there hasn’t been any looking back. With a “Made in Manamadurai” claypot, he has travelled the world, performed in countless venues, collaborated with a number of national and international musicians, and is a winner of many national and regional awards.

After training under Vinayakram, Guruprasad also learned from another contemporary doyen of ghatam and percussion, V Suresh, and later under Madurai T Srinivasan. Learning from four Gurus makes his percussion a composite of diverse styles, traditions, techniques and aesthetics although he formally belongs to what is known as the “Thanjavur Bani”.

Also Read | The S. Varadarajan Interview: ‘The harder you work, the more gifted you get. Nothing happens naturally’

A lesser known fact about Guruprasad is that it was not on ghatam, but on mridangam, that Vinayakram trained him first. “When my father told him to take me as his student, he told my father that he would train me first on the mridangam to see how capable I was. One day, when I went for his class, he was busy doing some office work in another room and asked me to play till he got free. There was a ghatam in the classroom, a new one that sir had just bought. Out of curiosity, I started playing on it instead of the mridangam. I didn’t know that Vinayakram sir soon came from behind and was watching me.”

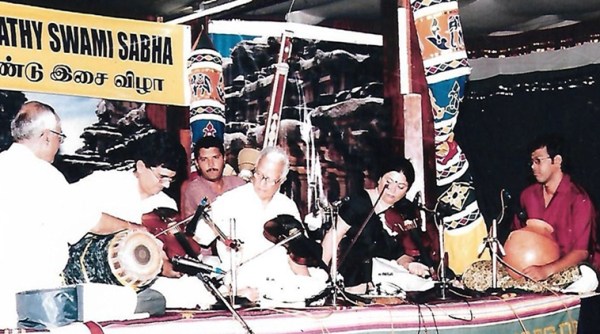

N Guruprasad accompanying violin maestro TN Krishnan. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

N Guruprasad accompanying violin maestro TN Krishnan. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

“Oh you are playing well!” Vinayakram said loudly from behind and the young Guruprasad got a little startled thinking that he would chide him for playing on a new ghatam without his permission. He immediately kept the ghatam back. “No no, don’t worry, keep playing,” Vinayakram said.” His next question was rather funny: “Who taught you mridangam?” Guruprasad told him that it was Vinayakram himself. “Oh, really? Anyway from today, I am going to train you only on the ghatam” he said. “From now on, don’t touch any other instrument”.

On the concert stage, Guruprasad is a delight to watch, not just for his art, but also for his elegant presence. He looks minimalist and effortless in his art, but what comes out of his humble claypot is sheer poetry.

Excerpts from the interview with G Pramod Kumar:

In Carnatic concerts, it’s always the mridangam that leads the percussion and hence it must be hard to find your creative independence and even stage presence. How do you find your space on the concert stage?

Very good question (laughs). That’s indeed a real challenge for the sub-accompanists namely ghatam, ganjira and the morsing. Let me talk about the ghatam. The first thing a ghatam artiste should know is where not to play. This was what my father taught me in my early days. He told me that only by knowing where not to play, I would know where exactly to play.

As you pointed out, mridangam leads the way most of the time. That’s the way a Carnatic concert is set up. We have to understand the rhythm patterns on the spot and respond to what they play: formations, korvais, nadais etc. The question is how do you retain your individuality even when what you do amounts to just responding to the ideas of the mridangist. The answer is spontaneity. We have to develop the competence for that spontaneity, for anticipating the moves of the mridangam and playing along. Moreover, don’t try to show your individuality in all the aspects of percussion in a concert; it should be good enough even if you can shine on one. Your creative ability is anyway going to show up in the thaniyavarthanam. So, in simple words, it’s about spontaneity and proportion.

How does it work exactly? This whole business of anticipation and impromptu responses?

The vocalist and the mridangist already have a plan, say at least 95 per cent; but the violinists and the ghatam players most often don’t know about it. It’s about being prepared to face the unexpected. We can’t be prepared when we don’t know what to expect, can we? We can only respond to what they do. If what we do (the ghatam players) syncs with what they do, it would sound nice and it would be our day; if it doesn’t, it’s a bad day.

All you can do in terms of preparation for such situations is to listen to a lot of their music and see what all they have done; but you still can’t be 100 per cent prepared. That’s also the thrill of classical music.

This means that when I listen to you in a concert, what I hear is a reflection of what the mridangist does.

Yes, sort of. That’s the role of the ghatam, you can’t play whatever you think. You have to follow the rhythm player, that’s the mridangam. We have to highlight what he’s playing.

But if the mridangist’s style is entirely different from yours – say somebody is playing all kinds of inappropriate solkettus (rhythmic formations) for a krithi – what do you?

You have to somehow adjust (laughs). You have no other way because you have agreed to play in that concert.

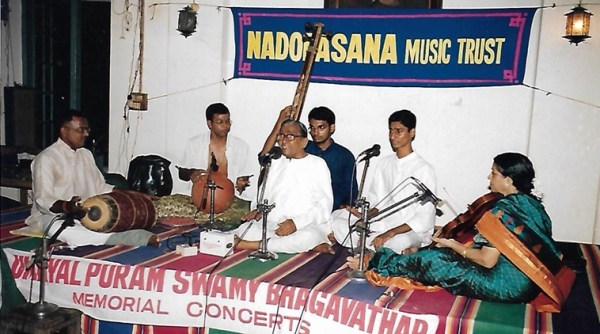

N Guruprasad in concert with Mandolin Srinivas. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

N Guruprasad in concert with Mandolin Srinivas. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

Is there a way in which the ghatam players can make it sound easier when the mridangists are doing too much?

If such a situation arises on stage, we can try our best to merge with it without adding to it. We can also stay silent or join with the mridangist in a gap without being intrusive.

Since we referred to playing for compositions (the kriti), what is your approach?

The first point to note is the tempo of the song and how the mridangist is playing. In every kriti, all of us – the vocalist, the mridangist, the violinist and the sub-accompanist – will have that little adjustment issues before things fall in place. Initially, any of us – the vocalist, the mridangist, the violinist or the ghatam player – can either go a little faster or slower. All the four will be together in a groove or nadai as well as the mood of the composition only after four or five lines. That’s when it will sound good to both the audience as well as us. Overall, I think we can match probably about 98 per cent when we play for compositions.

It’s a no-brainer that in a slower song, you can’t play at a higher tempo. You have to play the nadai that matches the tempo and emotion of the composition. See, the ghatam has a limitation – you can produce only four monotones on it and hence you can’t give a lot of expressions. Using these monotones, you have to give your 100 per cent, or rather 1000 per cent, to do justice to the song. If the mridangist is playing well, the ghatam will get aligned automatically.

Guruprasad was trained by Vinayakram on the mridangam first. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

Guruprasad was trained by Vinayakram on the mridangam first. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

You said about four monotones, how do you express even within that?

My father used to tell me that one has to listen to a lot of concerts because one has to truly embody the emotions in compositions and ragas. At some stage, even subconsciously, it will come to your mind. For instance, there’s a very difficult tempo called ‘rendu kattam kalapramanam’. Not that people haven’t played in that tempo beautifully, but you will acquire the skills only by listening to a lot over a period of time. It’s about forming a certain mindset and then playing accordingly.

Take the composition “Brovabarama”. You know the song, the raga as well as the composer only by listening to it again and again. Rhythms are also like that. Even if I know the composition well, where to play what nadai in that composition will happen only by mastering it by listening to it repeatedly.

Can you make modulations on the ghatam like some mridangists do?

Yes, especially, the “gumkis” or the bass strokes. There is this Umayalpuram Kothandarama Iyer style of playing in which bass notes can produce a lot of modulations. It’s not easy though. We can also match the “gumkis” that the mridangists play on the left side of their instrument with what we play with our belly.

But not many are doing the belly gumkis these days

Yes (laughs); they are now mostly doing it with their palm.

Why?

Because playing with the belly is strenuous and using the palm is easier. For using the belly, you have to open your shoulders and play.

But what you hear also is different – I mean between the sound produced by the belly and the palm on the mouth of the ghatam

Certainly. However, even playing the bass notes on the mouth of the ghatam with the palm also has variations. At least three – closed fully, half closed and fully opened. You can even try the swaras using that technique. You can actually produce four or five swaras. So, it’s not a bad practice either.

N Guruprasad at an early concert in Chennai with Vairamangalam lakshmi narayanan and T.Rukmini on violin. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

N Guruprasad at an early concert in Chennai with Vairamangalam lakshmi narayanan and T.Rukmini on violin. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

Which means that you can use it when the vocalists sings the chittaswarams?

Yes, certainly possible; but the problem is that it has to be audible as well. That’s why a lot of people are not using it.

Have you tried?

I have tried it in a recording for the background music of a movie. It was completely swaras and I played them with the base. It came out well.

But you need some sophisticated microphones to pick up the gumkis and nuanced sounds from the ghatam, don’t you?

Yes, there is a pick-up mic that was used first by Vinayakram Sir. It captures the beautiful tone of the ghatam very well. After him, other ghatam artistes also started using it. I am also using it for my concerts and recordings. The normal mics don’t pick up the tone and clarity of the strokes by the thumb and that’s where the pick up mic helps. For bass, we use a separate mic.

An interesting visual aspect of a ghatam artiste is his fingering. My understanding is that some people use totally unconventional fingering – particularly those who have learned other percussion instruments, but then shifted to ghatam. Will there be a difference in the way their ghatam sounds?

Yes, there will be a difference. For instance, when you play the mridangam, your fingers have to fall on certain places to get those tones right. Therefore, if you ask a Tavil player to play the mridangam, it may not sound like a mridangam. The same is applicable to ghatam as well. For the ghatam to sound perfect, you should play with proper ghatam fingering. If you don’t know the real fingering, it may even sound out of pitch.

As far as I have noticed, your style of ghatam is minimalist and is to embellish the singing. I don’t see you trying to stand out, but are trying to merge with the ensemble. Am I right? To me that’s your aesthetic. Where did it come from?

It primarily came from my father. He always used to tell me that you have to follow the composition, give the right expressions and present the mood according to the composition. His point was that if you play for the composition well, you will automatically play well for the thaniavarthanam (percussion solo) as well. I persisted with that point and have developed a style by listening to a lot of recordings, playing in concerts and practising with friends.

Many ideas occur to you while playing in a live concert, but you really don’t know how they will sound if you employ them. So practice is very important to know how such ideas will sound in a concert. Similarly, when people give us the feedback after a concert, we get to know what is good and what is bad. I certainly take negative feedback seriously and work on them to make sure that it won’t happen again.

According to Guruprasad, finding space on the concert stage is about spontaneity and proportion. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

According to Guruprasad, finding space on the concert stage is about spontaneity and proportion. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

Sometimes I have seen you playing just a few strokes, filling up and then slowly building up.

Yes, that’s how you pick up on the compositions. You have to gel with the mridangam. Instead of playing with it non-stop, playing at appropriate places, playing fillers and thus building up, you will develop a connect with the mridangist on the spot. That may also give him new ideas that will lead to an interesting tala-conversation on stage. If it works, we get a synchronous percussion that will sound quite pleasing to the artistes on stage as well as the audience.

Means, if you try those small interludes, he will also try to bring you in more?

Yes. That’s how it works.

Let’s go back a bit to your training as a kid. When you had your father as your guru at home, why did he send you to Vinayakram?

My father thought that being his son, I wouldn’t sincerely learn from him; so he himself took me to Vinayakram sir in 1991. Under my father’s training, I used to play a little by then. Since we had the instrument at home, I started playing on them from the late 1980s, and my father would teach me too; but the real formal education started with Vinayakram sir.

N Guruprasad receiving an ward from TH Vinayakram. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

N Guruprasad receiving an ward from TH Vinayakram. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

And when did you start playing for concerts?

From 1996, Vinayakram Sir used to involve me in some percussion (Thaniavarthanam type) concerts – those small ones during the Vinayaka Chaturthi processions. There were other boys like me too – some seven or eight of them. Unfortunately, none of them pursued it professionally. In 1998, I got an opportunity to play with the great violinist Sri TN Krishnan on his Karnataka Spic Macay tour. I played with him in 15 concerts. Although he was such a senior musician, he was extremely friendly and didn’t treat me like a rank junior. And subsequently I played several concerts with him. At that time I also learned from Suresh Anna (V Suresh) after obtaining permission from Vinayakram sir.

But Vinayakram must have been travelling all over the world those days?

Yes, he was very busy with the Shakthi tours, playing with Tabla maestro Zakir Hussain and also with a lot of Hindustani musicians. He was playing all over the world.

So how did you learn from him when he was away?

There would be somebody trained by him to teach us during his period of absence. He would know all his lessons. When Vinayakram sir returned, he would ask us to play what we had learned and he would correct if there were mistakes.

He had a lot of international influence and that must have rubbed off on you too?

Probably yes. My playing style is influenced by all the four Gurus of mine. In fact, I adopt the best from all their styles, I mean the things that I love the most in their art of ghatam playing.

What’s that difference in playing styles? For instance, between two stalwarts such as Vinayakram and Suresh?

Both are equally magical and worthy of emulation. If you sit close to Vinayakram sir, you will be dumbfounded by his impeccable fingering techniques which can be mastered only with extraordinary talent and years of commitment to the instrument.

Suresh Anna’s remarkable fingering technique is also very difficult to reproduce. It stands out for the ease and felicity with which he plays the unique double-hand gumkis. Both of them are huge assets to a concert. Their methods of enhancing a concert in their own individual styles is truly a lesson for all.

N Guruprasad says that his style of ghatam came from his father. “I have developed a style by listening to a lot of recordings, playing in concerts and practising with friends,” he says. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

N Guruprasad says that his style of ghatam came from his father. “I have developed a style by listening to a lot of recordings, playing in concerts and practising with friends,” he says. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

For the lay audience, can you give some tips as to what should one look for to appreciate the ghatam more?

It’s a little difficult to make a layman understand the intricacies of playing the ghatam because you need to know a little bit about the instrument. Of course, we can play in a way that the lay audience can enjoy, but to make them understand the difference between different styles is a little tough. For instance, you mentioned about mridangist playing the ghatam and employing their own fingering techniques. If you don’t know about the instrument, you won’t know the difference in sounds at all. Fundamentally it’s about the right tonality. If you play wrongly on the mridangam, anybody would realise that there’s something wrong because of the difference in tone, but in ghatam this doesn’t happen. I think if the audience have even a little knowledge on tonality, – the ability to distinguish the minute difference in tones – they would be able to appreciate the artistes more.

Who are your influences? Both in ghatam and other forms of percussions?

First is my father. Then my guru Vinayakram, followed V Suresh and Madurai T Srinivasan.

Have you played for movies? Some Carnatic musicians have told me that it’s not easy.

Oh yes, it’s not easy because of its unique demands. I have played for quite a number of movies in all southern languages. In a composition, we play in our style; but in movies, we should play what the composers want. Moreover, in a movie song what the composer gets is only three or four minutes in which he has to give all the expressions that’s demanded of him. That’s not an easy job. And we have to contribute to that. Both require different skill-sets and approaches.

Do you regularly play for movies?

Yes, I do. I have played for Ilayaraja sir, AR Rahman, Thaman, GV Prakash and many Telugu and Malayalam directors. I have also played for some Hindi movies. Recently, I have played for a song in Rahman’s “99 Songs”.

But in movies, the sound of the ghatam will be in small bits right?

Yes, usually 30-40 seconds. Ghatams are used not only in songs, but also in background scores.

Does the movie experiences contribute to adding colour to percussion in your concerts?

Yes. Playing for movies exposes you to a lot of genres that you are otherwise not in touch with on a regular basis. That will help you to adapt easily to the tempo/rhythm changes while playing in concerts. In addition, because of your exposure to various situations, unusual ideas may occur to you more easily.

N Guruprasad performing in a collaborative concert with Yogesh Samsi on Tabla. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

N Guruprasad performing in a collaborative concert with Yogesh Samsi on Tabla. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

What about the mridangam influences?

It’s primarily Palghat Mani Iyer, Palani Subramaniam Pillai, Murugabhoopathy Sir, TK Moorthy Sir and Palghat Raghu Sir. I have played a lot with Moorthy Sir and Raghu Sir and hence it’s only natural that I have been influenced a lot by them. I mean whatever I do, it will have their influences. Karaikudi Mani Sir, Trichy Sankaran Sir, Umayalpuram Sivaraman Sir etc also have influenced my art. Since I have played with them quite a bit, I have practised and presented a lot of their techniques on the ghatam. When you are exposed to stalwarts and also play with them, it happens naturally because you look up to them a lot.

International influences and influences by other forms of percussion?

The tabla has a lot of influence on me, mainly in playing running phrases. I like to match the Tabla probably because I have heard a lot of Vinayakram and Zakir Hussain playing together. I somehow like Tabla-style compositions. Among other percussion instruments, I also like the sound of the congos. Its rhythms also have influenced me a lot. Now, there’s a new instrument called the hand-pan. I am thinking of trying something on that.

They come with swara positions, right?

Yes, there are many sruthis in the hand-pan. For each raga, we have to buy a pan. It will be usually set to one scale and we can do whatever we want ON that scale. I have tried it at a friend’s place. It was interesting.

Do you listen to other forms of music?

I have heard a lot of John McLaughlin. I am also a fan of Zakir Hussain and regularly listen to all his recordings. In Hindustani, I listen to a lot of Rashid Khan and Bhimsen Joshi. I also listen to original folk music of Tamil Nadu.

Do the rhythms in folk music influence you?

The grooves will certainly influence.

Will they have groovy rhythms that you haven’t heard or played before.

The folk-rhythms may be familiar, but they may play in different formations. For instance, they may play the same 4-4 in different permutations and combinations. Their punch notes will be different and as a result, when we play similar grooves we may think of trying those accents. You might not have thought of those grooves till then.

Which is the most difficult part of a concert?

Neraval, because all four of us will be improvising on the spot. Neraval is all about impromptu musical imagination. So naturally, it’s the most difficult part.

What about Kalpanaswaras? How do you compare it with Neraval in terms of complexity?

In Kalpanaswaras, you can either follow the swaras or play the groove if it doesn’t work. Each percussionist will try his best to follow the swaras; if it doesn’t work, they play the nadai. But, in neraval you can’t do that because you have to follow the lyrics. You also have to see the placement of the lyrics and play expressively to match the meaning and music of those lyrics. You will know what and when to play only when you actually hear the neraval – where to be melodic and expressive, where to press, where to stop etc. Nobody would know which line would the singer pick up for doing the neraval.

Such unexpected situations can happen even in thaniyavarthanam wherein the percussionists are on their own. But if somebody sings the swaras in unexpected areas and make us do the thaniavarthanam, it will be difficult.

N Guruprasad receiving Sangeet Natak Akademy Award. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

N Guruprasad receiving Sangeet Natak Akademy Award. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

Can you elaborate on that please?

See, some will sing the swaras in unusual places which will also make the percussionist play the thani at an unusual place, which they may not have done earlier. It will be doubly difficult compared to the regular thaniavarthanam. The challenge is that you have to show your individuality, but play for the composition at the same time.

How do you handle the unfamiliar compositions?

The best thing would be to play the nadai. If we can anticipate well, we can also try picking up on the structure of the composition when they repeat the line.

What about the koraippu?

The mridangist would have already planned the koraippu. Some may tell the ghatam player in advance, some may not. Even if he’s not informed, the ghatam player will have to read the pattern on the spot and repeat it. It’s not easy, but there’s no other way. A creatively fulfilling aspect is that if you play along with the mridangam well in that koraippu portion, you will certainly get recognised. There are many such artistes who have gained such a reputation. What moulds us for these situations is practice although it’s a simple sounding word. Practice is also about building up innovation and thought-processes. When we practise with friends, we play at random and do a lot of impromptu give and take. One has to practise like that a lot to get used to totally unexpected situations. It will equip you to respond to whatever rhythmic challenges the mridangist may pose to you.

While playing the koraippu, you are at a disadvantage because you don’t even get enough time to pick up from what the mridangist plays and follow.

Yes, it’s a difficult prospect.

Guruprasad feels that playing for movies exposes one to a lot of genres that they are otherwise not in touch with on a regular basis, which in turn helps to adapt easily to the tempo/rhythm changes while playing in concerts. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

Guruprasad feels that playing for movies exposes one to a lot of genres that they are otherwise not in touch with on a regular basis, which in turn helps to adapt easily to the tempo/rhythm changes while playing in concerts. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

But soon, you both fall into the same groove, isn’t it?

Yes, afterwards whatever compositions the mridangist plays will be 99 per cent common – the Mohra and Korvai. Usually we won’t know the Korvai, so we watch him for one or two rounds and then play along. It’s always better to watch him for a round also because he himself may not know if what he’s going to try would work or not. If it works once, it will certainly work the second and third time.

Your role is difficult because you have to listen to both the mridangist and the vocalist?

Yes, also the violinist. They play an important role in the concert without a break and we also have a responsibility of enhancing their neraval and swarams.

In terms of the distribution of the percussion, how does it work because it’s always not mridangam for vocal and ghatam for violin, right?

It’s all eye contact. If we play something nice, sometimes the mridangist will gesture to us to continue. Such an understanding will automatically happen on stage. It’s not planned. Whatever sounds good works. Like mixing and matching.

Contemporary musicians that you enjoy playing with?

I like all of them. When I say this, I am not trying to be safe. I truly like all of them because I play with all of them and they are all so different. It’s an exciting prospect. Since I have heard and liked all genres of music, I like the music of all the musicians. Each musician will have some aspects that I am really fond of. Frankly, I feel fortunate to have been exposed to various styles of music because I play with a lot of them.

You may have played with almost all the present-day Carnatic musicians – old and young and men and women.

Yes

And there’s no men/women difference either.

Yes. For me, it’s all about music. If the music is good, I will be happy to play.

N Guruprasad credits his father, his guru Vinayakram V Suresh and Madurai T Srinivasan and his influences. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

N Guruprasad credits his father, his guru Vinayakram V Suresh and Madurai T Srinivasan and his influences. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

One of the musicians with whom you are seen the most is TM Krishna. In recent years, he sticks to the slow tempo for most part of his concerts. How do you adapt to such a tempo?

Yes, he is a trusted friend for many years and we share a great rapport both on and off the stage. Playing for any tempo requires focus and commitment, more so when it’s slow. Handling a slow tempo on the ghatam is difficult because unlike the mridangam it’s an instrument that doesn’t sustain sound. Giving your best at that tempo is therefore hard. One has to be very careful not to go faster as well because it will create a huge tempo-mismatch. Singing like that also is difficult.

You are also seen a lot with Sanjay Subrahmanyan, particularly in his signature concerts

With him, it’s been a long association that’s full of beautiful, unforgettable experiences, both during concert travels and also performances. I think I have been playing with him since 2002. When we travel with him, we talk a lot about cricket, mathematics, concerts and so on. Being on stage with him are outstanding experiences.

He’s also very innovative on stage, how difficult is that for you?

Of course he is, and it does pose interesting challenges. For instance in kuraippu, he will take a small number and will keep on improvising on that. We have to get that on the spot. If we don’t get it, he will tease us with a smile, we have to join in the next round. It’s an enjoyable sportiness on stage.

What’s the most pleasing part of a concert for you?

I think the “sruthi sudham” portions. For instance, if a vocalist is sustaining on the Sa, the mridangist will give only the sruthi and ghatam and violinist will also do the same. The pleasantness that you experience then, where everything together will be heard as Sa, all together as one note, is exceptional. I also like the “Tukdas” because of the happiness, bhakthi, peppiness etc.

I have seen some ghatam players struggling to match the mridangists because they are unable to decode the formations that he’s playing.

Yes, in my early years I too had struggled like that. It’s mainly because you haven’t had those rhythmic experiences before. As you hear and play more and more, you will get familiar with such formations.

It’s also because some mridangists play a lot of solkettu that don’t add much aesthetic value to a concert. Some also use inappropriate strokes. Why do they do that?

The appropriateness in accompaniment comes only from years of experience, listening to great masters and the guidance of a guru. We must also remember that a concert is a team effort and whatever we play should be in the interest of the concert.

Ghatam looks like a deceptively simple instrument. It’s made out of clay, but produces a sound with a metallic twang. Can you tell me something about the instrument?

There are three types of ghatam – Madras, Manamadurai and Bangalore. Now most artistes use only the Manamadurai ghatam because people have stopped producing the Madras ghatam. I also use the Manamadurai ghatam.

You get the metallic tone with sruthi sudham only in the Manamadurai ghatam. It’s made from a proprietary mix of clay that contains Iron and copper filings and manganese (for colour) and egg. It’s been made by some families for several generations and they alone know how to prepare the mix and bake it to the ghatam in the final form. The baking has to be at a particular temperature for the pot to get to a certain sruthi. As you know, each ghatam will have its own sruthi and getting that sruthi itself requires so much care.

Guruprasad has played with Bombay musicians such as Taufik Qureshi, Yogesh Shamsi, Sreedhar Parthasarathy, Rakesh Chaurasya, Sankar Mahadevan and Rajeev Mahavir. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

Guruprasad has played with Bombay musicians such as Taufik Qureshi, Yogesh Shamsi, Sreedhar Parthasarathy, Rakesh Chaurasya, Sankar Mahadevan and Rajeev Mahavir. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

So, making a ghatam takes minimum 5-6 days. In one lot, they will make about 150-200 pieces out of which the artistes choose the best. If I have to choose my ghatam, I will have to first look at all the ghatams that come out of the furnace in a lot and see how many of them have the desired tonal quality and uniform pitch. Only if all the walls are baked at that particular heat everywhere, it will have the same pitch across the ghatam. If it’s half baked, it won’t be uniform – different places will have different pitch. That examination itself will take about four hours. Once we separate the ones that are useful (the ones with good tonal quality and uniform pitch) from the entire lot, we get to select ghatams of different pitches of our choice. Since the pitch is fixed, we will have to buy many pieces so that we can keep changing them according to the pitch of the artistes.

Although the instrument comes with a fixed pitch, it comes down a bit as we keep playing because of a mild erosion of mud from the inside wall. Therefore, for a ghatam with a certain pitch, we will buy one with a slightly higher pitch. So, when it finally settles down, we will have the instrument of desired pitch.

Years ago, a lady in Germany had created a two-piece ghatam. Upper part had one pitch and the lower part another pitch. It was released in Germany and Vinayakram Sir only bought it. It’s still with him. The tone of that ghatam is very pure, like the ghatam of the olden days. It is big in size too.

Besides performing in concerts, N Guruprasad has played for Ilayaraja, AR Rahman, Thaman, GV Prakash and many Telugu and Malayalam directors. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

Besides performing in concerts, N Guruprasad has played for Ilayaraja, AR Rahman, Thaman, GV Prakash and many Telugu and Malayalam directors. (Image courtesy Rajappane Raju)

But don’t you apply clay and modify the pitch sometimes?

Yes, we can reduce a little bit on stage using clay. It happens when your instrument doesn’t have exactly the same pitch as the artiste. Some days, the artiste himself or herself might sing at a slightly lower level than their usual pitch and this is how we match their pitch.

Do you have to keep doing it throughout the concert?

No, if you do it once, it stays for the entire concert.

While choosing the ghatams, which are the hard ones to get – those with lower pitch or higher pitch?

Higher pitch, because the makers haven’t yet figured out the temperature at which they get high-pitched pots.

Will you be able to play if you get a normal clay pot?

No. It will produce only the sound of mud.

You have travelled the world with your ghatam and collaborated with many artistes outside the Carnatic genre. Can you name a few?

I have played with Bombay musicians such as Taufik Qureshi, Yogesh Shamsi, Sreedhar Parthasarathy, Rakesh Chaurasya, Sankar Mahadevan and Rajeev Mahavir. With Chaurasya, I have played at the Oval Cricket Ground. I have also played with Mandolin Srinivas in South Africa in a symphony orchestra.

N Guruprasad with Mandolin U Srinivas. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

N Guruprasad with Mandolin U Srinivas. (Image courtesy: N Guruprasad)

Thanks for reminding me about Mandolin Srinivas. You had a long association with him, didn’t you? Tell me something more about him before we wind up.

He was such a noble man! I am yet to meet another human being like him. None of us have been able to come to terms with his untimely passing.

Once I was on a concert tour with him in Jaipur and on the morning of the concert-day, I casually asked him what he was planning to play that evening. He said he was still undecided (like most do). In the evening, when we were in the car, going to the concert-venue, he asked me: “What do you think I should play?” “Play Gangeyabhushani, Sir.” I told him. “Okay, let me do that then,” he said.

The Gangeyabhushani he played that evening was out of the world. l still can’t explain the flow of the ragam. Similarly, I won’t forget the philharmonic orchestra concert in which I played with him in South Africa. He was literally on fire on the stage. The whole orchestra, the entire audience etc were awestruck by Mandolin Srinivas!

Apr 20: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05